Warby Parker has trained its sights on the stylish, “post-wealth” millennial set—as customers and employees.

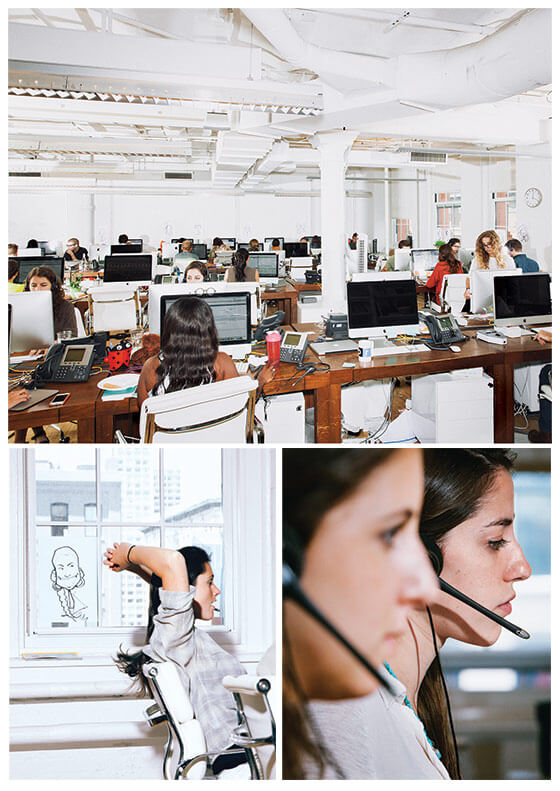

Early one morning this summer, a gaggle of fresh-faced twentysomethings streams into an elevator at the Puck Building on Houston Street. “I like your shoes,” one girl tells another, smiling with a first-day-of-school shyness. They could be mistaken for NYU students—the university has space on the building’s second and third floors—but they all exit on floor five, at the bright white offices of Warby Parker, where two of the company’s founders, Neil Blumenthal and Dave Gilboa, are preparing to kick off their weekly companywide meeting. Dressed near-identically in the uniform of the New York start-up entrepreneur—tailored button-downs, dark jeans—the pair look as streamlined as a couple of smartphones and operate just as efficiently, waiting for fashionable backpacks to be dropped into chairs and Fage yogurts to be procured until precisely 8:30 a.m., when Blumenthal, tall and dark-haired with a voice that recalls Ira Glass, calls the meeting to order.

First on the agenda is the online retailer’s new stores in New York, Boston, and Los Angeles, the opening of which came as a surprise to the industry, since Warby Parker has fashioned itself as a pioneer in the new wave of e-commerce. The founders take a kind of fatherly pride in maintaining transparency with their employees, and so Blumenthal walks them through the reasoning. “One of the things we’ve learned is that if you really want to be a dominant player, you need to have a presence in both online and brick-and-mortar,” Blumenthal tells the group. “Especially in categories like fashion. Other categories, like toilet paper or diapers or paper towels, those are going to shift online more dramatically.” He goes on to cite an example: “My wife and I have actually never bought diapers in a store, which is kind of amazing,” he says. “There are probably a few other people here that have also never done that.”

There’s a pause, then a wave of laughter as Blumenthal realizes his mistake: No one in this audience is buying diapers. Blumenthal, 33, and Gilboa, 32, are pretty much the oldest people at the company.

After that, various departments offer presentations to the class: The social-media coordinator introduces a new strategy; representatives from marketing show off the company’s recent video collaboration with the designer Chrissie Miller, a soft-focus seventies-style short of a Coney Island dance-off inspired by The Warriors and West Side Story. There is a lot of up-talking? That manner of speech in which you phrase a fact as a question? It seems contagious? Especially among the newer employees? Many of whom still have, stuck to their chairs, balloons with an image of a cow saying nice to meat you. “This is actually our biggest number of hires in one week,” Blumenthal tells his employees, whose numbers have swelled to 250. “Come on up,” he says, Ira Glass morphing into Bob Barker, “and give us your fun fact!”

Fun facts are a Warby Parker tradition, a getting-to-know-you exercise that upholds one of Warby Parker’s eight core values, written on the wall of the kitchen: “Inject fun and quirkiness into everything we do.” While no one has managed to top one early hire’s mind-blowing revelation that she once held Michael Jackson’s infant son Blanket, the newest additions to the team are unlikely to disappoint—the company employs a “cultural swat team” that weeds out dullards in interviews with questions like “When was the last time you wore a costume?”

First up is Kate, from product strategy, who describes herself as a rodeo enthusiast. “Actually, a champion barrel racer?” Next is Priyata, who recently returned from a trip to war-torn Syria, “where we heard missiles but survived?” Natalie, from customer experience, was a “fan dancer” for Beyoncé in the Super Bowl halftime show? Julie lost her sense of smell crowd-surfing at 16? Ryan was the vocalist in a metal band? Emily recently rode an elephant named Pancake?

Blumenthal closes the meeting by talking about upcoming opportunities to volunteer with nonprofits like Venture for America and the Network for Teaching Entrepreneurship. (“Do good” being another one of Warby Parker’s core values, not to be confused, Blumenthal will tell you, with “Don’t be evil”: “Doing good is proactive—‘How can we make this world a better place?,’ not ‘How can we prevent doing something bad?’ ”) He announces a new employee happy hour, “for those of you that can drink.” Then Gilboa proffers one final thought. “We’re very happy to announce that this is the first time a sun SKU—the Downing in walnut tortoise—has made it into the top five best-selling glasses for the month,” he says.

Oh, right! The glasses.

What with all the stuff going on at the Warby Parker offices—the Lunch Roulettes and Instagram Photo Walks, the earnest philosophies and rococo marketing ventures, the pop-up store in a yurt, the map of places to read in downtown New York, the blog with reading recommendations and “style stories” about their friendly and good-looking staff—it’s easy to forget that the whole point of the company is to sell glasses. The kind people wear in order to see. That’s it. Glasses.

What with all the stuff going on at the Warby Parker offices—the Lunch Roulettes and Instagram Photo Walks, the earnest philosophies and rococo marketing ventures, the pop-up store in a yurt, the map of places to read in downtown New York, the blog with reading recommendations and “style stories” about their friendly and good-looking staff—it’s easy to forget that the whole point of the company is to sell glasses. The kind people wear in order to see. That’s it. Glasses.

Warby Parker is widely viewed as one of the great success stories of the post-recession age, and a model for how digital start-up culture can work in fashion. The simple model of producing stylish, affordable eyeglasses that buyers can order online and try at home—five pairs, five days, $95—has spawned countless imitators (including underwear purveyor Jockey, which one blogger dubbed “the Warby Parker of titties,” after it began offering bra “fit kits” online). Blumenthal and Gilboa have impressed high-profile investors such as J.Crew’s Mickey Drexler, American Express, and the hedge fund Tiger Global Management; a financing round earlier this year valued Warby Parker at a reported $300 million. Along the way, they’ve managed to establish themselves as part of a vanguard of consumer-friendly, socially responsible young “disrupters”: rhapsodized about by those trying to understand the 18-to-34 demographic, revered by their employees, who are also their customers. And they’ve done all this by making glasses—the province of nerds and librarians and Steve Urkel—seem cool.

“Glasses are cool,” reasons Blumenthal, who wears nonprescription versions of the frames Warby Parker sells. He cites the recent remake of 21 Jump Street, in which characters head back to high school to discover the script has flipped: The jerky jocks are outcasts, and creative kids rule the school. “We’re lucky enough to be living in that moment,” he says, “where it’s finally cool to be smart and thoughtful and to be creative.” The moment, they reckon, is theirs for the taking.

“What we really want to do,” Blumenthal says with the confidence of someone who grew up being told he could do anything he wants and has thus far found this to be true, “is to change the way business in America is done.”

Gilboa, shier, simply nods, as if to suggest this outcome is imminently possible. Warby Parker core value No. 8: Set ambitious goals.

You don’t have to look very hard to find Warby Parker’s origin story. It’s etched on the countertops of the flagship on Greene Street, where this summer a steady stream of tourists and interns could be found peering into mirrors to check out how they looked in frames named after poets and writers, surrounded by terrazzo floors, a bronze bust of someone old and dignified, and floor-to-ceiling bookshelves with tomes arranged and labeled by color (kelly, aubergine). The space, which its designer, Anthony Sperduti of Partners & Spade, calls “functional,” “intelligent,” and “absolutely not hipster,” is intended to resemble a library, inspired by the company’s “literary history,” as Blumenthal puts it (Warby Parker is an amalgam of two Jack Kerouac characters). But as the time line will tell you, Warby Parker was conceived not in a library but in the computer lab on the University of Pennsylvania campus, where the founders met at Wharton business school in 2008. Gilboa, a would-be medical student, had enrolled after his disillusionment with the health-care industry led him to Bain & Company and the idea that business was the most powerful way to change the world. Blumenthal, an international-policy wonk who had studied at the Hague, had come to similar conclusions after a stint at VisionSpring, a nonprofit that helped distribute low-cost eyeglasses in India and El Salvador.

“We were down in the computer lab, and Dave started describing how he just lost his $700 glasses,” Blumenthal recalls. Two other students, Andrew Hunt and Jeffrey Raider, commiserated, and it turned into a confab. “Jeff’s glasses had recently broken, and Andy had this amazing idea to sell glasses online.”

Blumenthal was the only one who didn’t wear glasses, but through VisionSpring, he’d learned a few things about the optical industry. Most significant, that it was controlled by one giant company, Luxottica, which owns everything from Ray-Bans to Oliver Peoples and runs outfits like Pearle Vision and LensCrafters. Its near-monopoly status enables the company to charge high prices and enjoy high profit margins. VisionSpring had managed to circumvent this by manufacturing its own frames … and if they had done it for people in the developing world, why couldn’t four business students do the same thing for people like, well, them? “At that moment, the lightbulb went off,” says Blumenthal. “But then, of course, we all had to go to class.”

Blumenthal was the only one who didn’t wear glasses, but through VisionSpring, he’d learned a few things about the optical industry. Most significant, that it was controlled by one giant company, Luxottica, which owns everything from Ray-Bans to Oliver Peoples and runs outfits like Pearle Vision and LensCrafters. Its near-monopoly status enables the company to charge high prices and enjoy high profit margins. VisionSpring had managed to circumvent this by manufacturing its own frames … and if they had done it for people in the developing world, why couldn’t four business students do the same thing for people like, well, them? “At that moment, the lightbulb went off,” says Blumenthal. “But then, of course, we all had to go to class.”

Later, they reconvened at a bar. “We looked at this huge industry that had no innovation, where there were no brands that evoked passion or that people were really proud to be associated with,” Gilboa says. “And we just thought there was a huge opportunity to disrupt an industry and create an iconic brand, a for-profit business that did good in the world and could inspire other companies.”

Over the next year and a half, Wharton became an incubator for Warby Parker. “We spent a lot of time crafting the brand architecture and arguing over ‘What do we stand for?’ ‘Who are we?’ ‘What is the aesthetic point of view of the brand?’ ” says Blumenthal.

At the time, the Great Recession was changing the landscape. Suddenly, the days of Paris Hilton and Sex and the City and conspicuous consumption looked dated, even obscene. “All this ‘How much you make,’ and the thing about the Joneses, and SUVs or Mercedes or whatever it is—those things no longer matter as much, especially to millennials,” says Blumenthal.

“Like, in the eighties,” he continues, “there was nothing cooler than a red Porsche. Now there’s nothing douchier than a guy with a polo shirt with a popped collar, driving a red Porsche. Because it’s flashy, it’s obnoxious.”

The Warby Parker brand would stand opposed to this kind of obnoxiousness. The design would resemble those of high-end manufacturers—no lion heads here—but the prices would be low, though not so low as to appear poor-quality, or conjure visions of sweatshops. Yes, to make a product under $100, they would have to manufacture in China. But they would soften this hard reality by having their factories vetted by Verité, an organization that, Blumenthal would later tell employees, “helps companies achieve the potential they have to make a positive change in the labor world.”

The overall concept was enlightened self-interest, with a product geared to appeal to the vanities of people like themselves: stylish yet practical, moneyed yet conscientious. The kind of people who think of themselves as more than a collection of data points connoting exceptional privilege (private schools, Ivy League colleges, Wharton, Bain & Company). Who carry feed bags to restaurants with $24 entrées.

“When we looked out at the world of brands, they tended to think of aspiration as wealth,” says Blumenthal. “But when we talked to our friends and looked at macro trends, particularly of the millennials, the No. 1 goal of everybody is not to live a life of just buying a bunch of very expensive objects. I think today people would rather go see the mountain gorillas in Rwanda and have an amazing experience and tell their friends about it. That has more about social capital than, you know, taking a private plane to St.-Tropez.”

They figured that traditional advertising wouldn’t work with this market. “We tried to come up with creative ideas that were different and interesting enough that someone wants to share with their social network, or they’re going to a dinner party and they want to bring up this conversation, because it’s just different and unexpected,” says Gilboa. “Basically we were trying to find as many opportunities to tell our story.” Which Blumenthal launches into a few minutes later: “How we started this business to radically transform the optical industry, bring down prices, and transfer billions of dollars from these multinational companies to normal people. And, thinking more broadly, how we wanted to demonstrate that business can be profitable and can do good in the world, and it doesn’t have to charge a premium for it.”

In fact, Warby Parker wasn’t the first to bite at the ankles of the giant Luxottica by offering a lower-priced product online. “I wouldn’t say that they disrupted the category or they discovered it,” says Roger Hardy, the founder of Coastal, a Canadian company that stuck its flag in that particular sand back in 2000. “There are lots of disrupters,” he says, among them companies like Geek Eyewear, Brooklyn’s Classic Specs, and a company called Salt Optics, which sued Warby Parker for trade-dress infringement. “They are a participant.”

In fact, Warby Parker wasn’t the first to bite at the ankles of the giant Luxottica by offering a lower-priced product online. “I wouldn’t say that they disrupted the category or they discovered it,” says Roger Hardy, the founder of Coastal, a Canadian company that stuck its flag in that particular sand back in 2000. “There are lots of disrupters,” he says, among them companies like Geek Eyewear, Brooklyn’s Classic Specs, and a company called Salt Optics, which sued Warby Parker for trade-dress infringement. “They are a participant.”

But in the current atmosphere, Warby’s Samson-and-Goliath story and pared-down aesthetic have stood out. “It’s cool, but it’s not too cool,” says Ben Lerer, 31, the Thrillist co-founder and scion of Lerer Investments, who became an early investor in the brand. “It’s premium, it’s sexy, but it’s not too sexy. It’s aspirational but not douchey or showy or snotty.” GQ and Vogue wrote glowingly of their launch, and a few days after the website went live, the company found itself so inundated with orders it ran out of inventory. It ended up hitting first-year sales targets in three weeks, the founding employees shipping boxes madly from Blumenthal’s apartment in Philadelphia.

Not long after, Raider and Hunt splintered off, Hunt to join a VC firm and Raider to found Harry’s—the Warby Parker of shaving, in that its online razor business intends to disrupt another industry that’s virtually monopolized. (They remain on Warby Parker’s board.) Gilboa and Blumenthal moved to New York, first to a small office near Union Square, then to the Puck Building, the site of Neil Blumenthal’s bar mitzvah and the offices of 28-year-old Josh Kushner, whose VC firm also became an investor.

At 9 a.m., 23-year-old Mikayla Markrich presses a manicured finger to her blinking desktop phone. It’s a guy in Portland, saying he never received his package of home-trial glasses. Markrich looks up the UPS tracking number, which says the package—the five pairs of $95 glasses—was left on the porch, a frequent occurrence with UPS. “They don’t care at all,” she says, frowning.

Markrich (fun fact: She was a Segway tour guide in her native Hawaii) went to Parsons, intending to work in the fashion industry, but the atmosphere was a little too Devil Wears Prada for her gentle soul, and when Warby Parker offered to promote her from her part-time job in the company showroom to a full-time one in customer experience, she ditched her career plans. “I know that technically it’s like a call-center job?” she says between phone calls. “But it doesn’t feel that way. You think of the stereotype: The people are old; they’re miserable; it’s kind of a dead-end job. Here, everyone is so young and so smart. And we aren’t treated as though we’re just the customer-service representatives. We’re viewed as part of the team,” Markrich says. “Coming from fashion, where people were so mean, the atmosphere here was just so much better,” she says, gesturing to the rows of cheerful colleagues. “People are happy.”

Keeping employees happy isn’t just a nice thing to do; it’s good business. Which is part of what makes Warby Parker so attractive to investors like Amex, which got burned in the last dot-com boom. “It’s not, like, Elon Musk sending whatever the fuck he is doing to the moon, that’s next-level shit,” says Lerer. “It’s just good old-fashioned amazing execution.” Earlier this year, the company conducted an internal survey asking employees why they were attracted to Warby Parker and why they’ve stayed. “And to both of those questions, compensation was dead last,” says Blumenthal. “It was culture and opportunity to learn and have an impact.” Every new employee gets a gift certificate to a Thai restaurant (the cuisine of choice during the company’s founding days); a copy of The Dharma Bums; a short history of the Puck Building; and a free pair of glasses, whether or not they need them. In the vein of start-ups, employees who stick around more than a year are offered equity.

In a few years, Markrich thinks she’ll maybe go back to school for an M.B.A., inspired by her work here. “I really believe in what we do and what the company stands for,” she says, hand hovering over the ringing phone. “I do think they are going to change the way business is done.”

She picks up the receiver. On the other end is a guy whose dog ate his glasses. “Destroyed them,” he says.

“Well, that’s not your fault,” Markrich says and offers him a discount on a new pair. After filling the order, she sends a follow-up e-mail to let him know they’ve shipped. “I hope they make you jump for joy,” she types.

“So what happens when Luxottica comes and offers you a billion dollars?” asks a guy in the audience at the Brooklyn Brewery, where Gilboa is sitting on a panel titled “The Blurring of Retail and What to Expect Next,” at this year’s NeXt conference. Gilboa blushes.

It’s a good question. At the moment, the venture-capital firms invested in Warby Parker are content to allow the company to grow. But they are eventually going to want something back, through an IPO or, more likely, a sale. “They’re not just looking to make operating income,” says Jonathan Sherry, whose company, CB Insights, tracks the growth of private start-ups. “They want the big payday.”

So, perhaps, do the founders of Warby Parker, who, three years after business school, now find themselves mingling in rarefied circles. Earlier this year, Gilboa Instagrammed a picture from Richard Branson’s Necker Island, and Blumenthal tweeted about “hanging” with Jessica Alba. The night before the company meeting, they had had dinner with Silas Chou, the billionaire investor who took Michael Kors public. Blumenthal recently bought a $3.5 million apartment, and his wife recently posted on Instagram a picture of a pile of Chanel bags. And Warby Parker itself has participated in some one-percenter-ish stuff, like a promotion aboard the Standard Hotel’s seaplane to the Hamptons. “But it was a plane inspired by Rin Tin Tin!” Blumenthal protests. “Not only did you get a pair of glasses, but you got CliffsNotes of great American novels!”

At the conference, Gilboa sidesteps the question by answering it directly. “Right now, I think all of us, everyone involved, and all of the customers, would be really disappointed if we sold to Luxottica,” he says. “That’s certainly not in the cards.”

If they were to make a deal, Blumenthal says, they’d want to do it “thoughtfully,” like their friends at green-cleaning company Method, who sold to environmentally friendly Belgian manufacturer Ecover, making it the world’s largest green-cleaning company. “At the moment, the eyes on the prize is: How do we build scalable infrastructure, and how do we build a profitable business and lifestyle brand that, you know, really resonates with people?”

Which Warby Parker does. For now. But their chosen demographic is as fickle as it is desirable. “Two years ago, when someone asked if my glasses were Warby Parker, it was typically a stylish British woman or an actor/ironic bike messenger/model,” says a young entrepreneur who was tipped off to Warby Parker glasses by a friend at Harvard Business School. “Now it tends to be bros in Bears jerseys on the subway.”

The killer, he says, was when the cashier at Costco struck up a conversation about the frames he was wearing. “He said he had the same ones at home, and did I like the ones he was wearing currently?” he says, sighing. “I haven’t worn them since.”