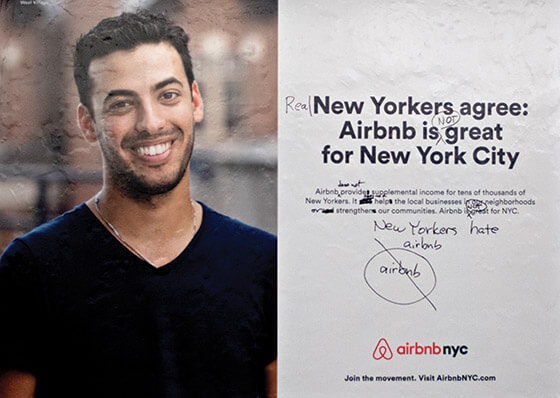

One morning a few months ago, New Yorkers opened their eyes to a city that, seemingly overnight, had been blanketed in advertisements for a company calledAirbnb. Bright white and crisp as newly fallen snow, each ad featured a smiling New Yorker and a short blurb about how the website, which brokers deals between travelers and people with a spare room or home to rent, had transformed his or her life, spiritually or financially. “New Yorkers agree,” read the tagline on each. “Airbnb is great for New York City.” The ads were cheerfully combative, as though this company with the puffy-lettered name were defending itself against some kind of enemy. Though it was unclear who or what that enemy was, or what they wanted MTA riders to do about it.

But like the snow in New York City, subway ads do not remain unsullied for long. By day’s end, someone had scrawled a retort on a poster of Carol, a dashiki-wearing mom, at the Canal Street station: “The dumbest person in your building is passing out a set of keys to your front door!” Over at West 4th Street, a message in similar handwriting appeared under Bob from Astoria: “Airbnb accepts NO Liability,” it read. By 42nd Street, the mystery scribe or scribes had settled on a catchphrase of their own, “Airbnb is great”—and here they crossed out “for New York” and substituted “for Airbnb.” As the graffiti spread upward to Harlem and outward to Brooklyn and Queens, it started to become clear that this was no run-of-the-mill ad defacement; it was a countercampaign, the latest battle in a full-scale war over Airbnb, one pitting analog against digital, old school versus new school, East Coast against West Coast, rich versus poor. At stake was nothing less than the Spirit of New York.

“We’re privileged that people care enough to talk about us, is the way I like to think about it,” says Brian Chesky, Airbnb’s 33-year-old CEO, who is sitting at a table at the Radius café in San Francisco’s Soma district and speaking in a gentle tone that contrasts with the tense, let’s-do-this look on his face.

It’s late August, and it had been a challenging summer for Airbnb. Berlin and San Francisco were both looking to curb Airbnb’s activity in their cities. There had been a weird standoff at a woman’s Palm Springs vacation home, where two internet trolls took over and established legal residency. Even a happy occasion—the unveiling of Airbnb’s new logo—had gone south after the internet declared that it looked like mutant genitalia. And then there was the roiling discontent in New York. “No, I didn’t know about that,” Chesky says glumly when I mention the poster. “But really, every summer has been crazy,” he continues, looking up gratefully as his co-founder, Joe Gebbia, arrives. “Hey,” Chesky says. “I was just telling her how crazy it is that we started this company six years ago,” he adds, not too subtly, “from a three-bedroom apartment down the street.”

This is the purpose of today’s meeting: to revisit the company’s humble origins and reiterate its intention to be a force for good. It’s a critical time for Airbnb, which has metastasized from a postcollege project to a multibillion-dollar concern rumored to be mulling a public offering. Its success or failure, which will portend the future of the sharing economy as a whole, depends in large part on the company’s ability to convince New York City—both its largest market and a petri dish that seems to contain every problem it could conceivably face—that people are, for the most part, decent and more likely in the face of temptation to choose the greater good over personal profit. Beginning with the founders themselves.

Chesky and Gebbia met at the Rhode Island School of Design. Art school may seem like an odd breeding ground for tech entrepreneurs. But the rhetoric there was very much aligned with Silicon Valley’s. “The teachers were like, ‘You’re a designer,’ ” says Chesky. “ ‘You could redesign the world you live in.’ ” To Chesky, the son of social workers from upstate New York, this idea was very empowering. “Like that George Bernard Shaw quote,” he goes on, reeling off what has become Silicon Valley’s unofficial motto: “ ‘The reasonable man adapts himself to the world; the unreasonable man persists in trying to adapt the world to himself. Therefore, all progress depends on the unreasonable man.’ ”

After school ended, Gebbia moved to San Francisco and launched his first business, inspired by the lengthy critiques, or “crits,” in which art students sit in a studio discussing one another’s work. “Everything’s covered in charcoal dust and paint,” he says at the restaurant. “So at the end of the day, you stand up and there’s literally a bun print on the seat of your pants. And I thought, What if there was a better way?” He came up with a prototype for a butt-shaped cushion he called CritBuns, which he manufactured and began selling to art students. Meanwhile, Chesky had gotten a job as an industrial designer in Los Angeles, where he was miserable. “It wasn’t what they told me at RISD,” he says. “I was living in someone else’s world, and it just felt very uninspiring.”

Not surprisingly, CritBuns was not a worldwide sensation, and by the time Chesky arrived, Gebbia was on the verge of losing the loft Chesky was supposed to move into. “I had $1,000 in the bank,” Chesky says. “And I hadn’t planned to do any of this. And so we’re talking and we realized there’s an international design conference that’s coming to San Francisco. And so Joe said, ‘We should just create a bed-and-breakfast at the conference.’ ”When Gebbia sent him a pair of CritBuns, Chesky had a revelation. “I was like, Wow,” he says. “ ‘He did it. He’s doing it!’ ” When a spot opened up in Gebbia’s loft, he decided to move there. “It felt like San Francisco was where it was all happening,” he says. “Like, if you were a painter in the 1400s, you wanted to be in Italy.”

Not surprisingly, CritBuns was not a worldwide sensation, and by the time Chesky arrived, Gebbia was on the verge of losing the loft Chesky was supposed to move into. “I had $1,000 in the bank,” Chesky says. “And I hadn’t planned to do any of this. And so we’re talking and we realized there’s an international design conference that’s coming to San Francisco. And so Joe said, ‘We should just create a bed-and-breakfast at the conference.’ ”When Gebbia sent him a pair of CritBuns, Chesky had a revelation. “I was like, Wow,” he says. “ ‘He did it. He’s doing it!’ ” When a spot opened up in Gebbia’s loft, he decided to move there. “It felt like San Francisco was where it was all happening,” he says. “Like, if you were a painter in the 1400s, you wanted to be in Italy.”

Gebbia had three air beds from a camping trip, and his former roommate Nathan Blecharczyk designed a website for them at Airbedandbreakfast.com. The first weekend, they had three guests.

“We’d make them breakfast in the morning—we would get fresh OJ and the best Pop-Tarts that you could imagine,” says Chesky. “We’d give them change to give to people when they walk through the Tenderloin.”

“It’s part of the San Francisco experience,” explains Gebbia.

“The more important thing is we actually made friends,” says Chesky. It was likeThe Real World, but less dramatic. “And after waving them good-bye, we realized: There’s a bigger idea here.”

“What if,” says Gebbia, “you could book a room in someone’s home as easily as you could a hotel?” He pauses. “Actually, it took a while for us to get to that.”

At first they stuck with the concept of air mattresses at conferences, which they promoted at the Democratic and Republican National Conventions in 2008 by making commemorative boxes of “Obama O’s” and “Captain McCain’s” cereal that they designed and hot-glued together in their kitchen. “I remember thinking to myself, like, Did Mark Zuckerberg ever make cereal?” says Chesky.

“At this point, we were each $20,000 to $30,000 in debt,” says Gebbia. Did they consider getting jobs at, like, a coffee shop?

“No way,” Gebbia says automatically.

“Picasso said that, like, creativity comes from constraints,” says Chesky. He has developed the start-up founder’s tic of sprinkling one’s speech with quotes and anecdotes from great men that subtly imply belonging in the same class of genius. (In fact, Picasso said no such thing. While the website startupquote.com attributes the line to Twitter founder Biz Stone, it’s most likely from a psychology book called Creativity From Constraint, which discusses how Picasso and Braque created Cubism by imposing restrictions on their painting. But hey, the man is designing the world around him.)

Chesky talks the talk, but five years ago, he was still very much an outsider, so much so that when a friend offered to introduce them to some angel investors, he actually thought the guy believed in angels. “And he’s like, ‘No, don’t worry. They’re people, and they’ll give you a $20,000 check over dinner.’ ”

One of those people was Paul Graham, a founder of tech incubator Y Combinator and the Zeus of Silicon Valley, from whose head many start-up quotes hath sprung. “He said, ‘Find 100 people that love you,’ ” says Gebbia. “Because it’s better to have 100 people love you than a million people or users that just kinda like you.” At that point, Airbedandbreakfast.com did not have a lot of users, but the greatest concentration of them was in New York. “So Paul Graham said, ‘Go to New York!’ ” says Gebbia.

At first, Airbnb—they shortened the name in 2009—was a hit mainly with their peers: millennials who were a tad more discriminating than the kids who booked with Couchsurfing.com. As the number of listings increased, the customer base grew, and it became a bona fide substitute for hotels. Then the financial crisis happened, and it became “so much more,” says Chesky.

He pulls up an email on his phone from a host who’d rented out her place on the site in 2009: “ ‘Hi Airbnb, I’m not exaggerating when I tell you that you literally saved us,’ ” he reads. “ ‘My husband and I just married after having lost our jobs and investments in the stock-market crash. We watched our savings dwindle to a point where we didn’t have enough money to pay our own rent … You gave us the ability to keep our home.’

“Like I say,” Gebbia says solemnly. “We don’t provide houses; we provide home.”

If the crash had never happened, Airbnb’s success may have been more gradual. But conditions were conducive to rapid growth. Not only were people looking to save money; they were pissed at being exploited by the system, and using the site felt gratifyingly subversive. For hosts, there was a beautiful kind of symmetry to it: Banks had leveraged people’s homes to make money; now they could do it for themselves. And guests liked that when they stayed at an Airbnb, they were paying a person, not a corporation.

Airbnb now hosts roughly 400,000 guests a night. This spring, the company raised a round of funding that valued the company at $10 billion, thereby ensuring the founders will never have trouble paying rent again. They’re still in the same apartment, by the way. “It reminds me of our roots,” Chesky says, which is one of the reasons they constructed a life-size replica of it in Airbnb’s vast new headquarters in San Francisco, a sprawling tower of glass and steel that also houses replicas of their favorite Airbnbs in cities like Paris, Copenhagen, and Bali; a cafeteria serving free healthy cuisine; a climbing-ivy wall regularly spritzed by a landscaper; and a gymnasium-size model of the company’s new logo. “People warned them it looked like a vagina,” one employee says, walking by the curvy fiberglass object on the mezzanine.

In 2009, 21,000 people stayed in Airbnbs. In 2010, the number rose to 140,000, and then the following year to 800,000. Venture-capital funding poured in. Chesky was elected CEO. In interviews, he began referring to Airbnb as a “movement” and as being at the forefront of “a revolution.”

In 2009, 21,000 people stayed in Airbnbs. In 2010, the number rose to 140,000, and then the following year to 800,000. Venture-capital funding poured in. Chesky was elected CEO. In interviews, he began referring to Airbnb as a “movement” and as being at the forefront of “a revolution.”

Chesky is right. It is crazy that just six years ago Airbnb was the loopy idea of a couple of art students and now it’s a giant corporation, thundering around the globe, influencing policy decisions, blundering into discussions about economics and technology and class. Like a cute kid who has rapidly matured into a horny teenager, it’s gone from being a small company with presumably good intentions to a corporation large enough to have questionable ones. “When you’re a two-person start-up, everyone wants you to succeed,” says Alfred Lin of Sequoia Capital, an early investor. “And then when you’re a big guy, and you start throwing your weight around to get what you want …”

Well, that’s when people stop being polite. And start getting real.

In New York, Airbnb happened slowly and then all at once. What’s that about, you’d wonder, as you saw a group of tall Swedes dragging their suitcases down a Brooklyn block. Then Airbnb-ing became a verb and a fact of New York life. You saw them everywhere: fumbling through change purses at the coffee shop on the corner, walking through Smorgasburg in unwieldy packs, swiping their MetroCards slowly and ineffectively while a line of locals groaned softly behind them. “You get a lot of French, Germans, Scandinavians,” says a friend of mine who lived for a year off renting her Williamsburg studio. “You can get Australians if you set your calendar out far enough. They like to plan ahead.”

Soon, everyone had had some kind of Airbnb Experience, as a host or a guest. There were happy stories: Once, someone’s Irish grandmother cleaned my friend’s place top to bottom thinking it belonged to a friend of her grandson’s—“he didn’t want her to know he was paying for it, which was so sweet.” And there were horror stories: “And then”—this is another friend—“I walked into the kitchen and the guy was standing there totally naked.” Then there were the real horror stories, of the genre Businessweek dubbed “Airbnb noir.” One hostreturned to his Chelsea apartment to find it the site of an “overweight orgy” (as the New York Post put it), and a prostitute who used someone’s East Village apartment for in-calls got stabbed by one of them. Encounters with the dark side of humanity—not to mention their puke, feces, and “dark and curlies,” per the Airbnb message board—this was not the kind of intimacy the founders intended to foster. But that was just one of the problems they didn’t foresee.

It wasn’t long before some of these stories made their way to the office of State Senator Liz Krueger. Located in a nondescript office building on the far, far Upper East Side, behind a rack of scaffolding and a row of construction workers doing a modern-day reenactment of the famous photograph of guys lunching on an I-beam, Krueger’s tiny warren of rooms is basically the opposite of Airbnb’s airy headquarters. As are the senator’s opinions. “She lives to destroy us,” one person at Airbnb complained. But to be fair, she’s been trying to destroy businesses like Airbnb since Chesky and Gebbia were in short pants.

“How long have I been working on this, Andrew?” asks the blonde, chatty senator, peering out from behind her cluttered desk.

“It feels like forever,” says her earnest 28-year-old spokesman, Andrew Goldston.

In 2002, not long after Krueger took office, she began getting calls from constituents complaining about short-term rentals in their buildings. “Somehow the landlord had made a deal through an Italian visitor website,” she says. “Now, Ilove Italy. Italy’s my favorite country to travel to, so don’t get this wrong. But it was like, all these elderly people living in rent-regulated apartments, and the landlord was marketing specifically to young Italian men who traveled, like, in groups of ten to 20. And groups of young men—it doesn’t matter what country they come from—they drink. And they party. And, that’s okay. It’s okay to be a wild, fun tourist, and we have laws for hotels about security and noise and multiple levels of fire code for large groups of loud, raucous, partying kinds of tourists. But apartment buildings where people live are not set up for that. So it was like, ‘Help, I’m being inundated by, like, drunk, wild young men’—I don’t mean to be sexist, but they happen to be young men—‘every night who are vomiting in my hallways. And playing soccer against my wall. And singing and throwing up.’ ”

Back then, the industry was fairly fragmented. Other than Craigslist, with its hit-or-miss reputation, or sites like HomeAway or VRBO, which dealt only with pieds-à-terre and vacation homes, there was no real clearinghouse for short-term stays in residential buildings.

There were a lot of stories like that, enough that the senator formed a small coalition to figure out how to handle them. Their concern wasn’t just with noise or safety, although it was that; it was also that long-term tenants were being harassed out of their buildings by landlords who’d figured out that increasingly desirable Manhattan real estate was worth more per night than per month. “I think, individually, this group of landlords each came up with this fabulous idea, Oh, I can make some fast, bigger money this way,” says Krueger.

“But then Airbnb came on the scene,” says Goldston. “And that opened up the floodgates.”

In 2010, Krueger and State Assemblyman Richard Gottfried presented a bill that made it illegal for New Yorkers living in multiple-unit dwellings to sublet their abodes for less than 30 days. The new law didn’t really compromise Airbnb’s original vision. People in multiple-unit dwellings could still have Real World–like experiences by hosting people in their apartments, as long as they stayed present. And owners of freestanding brownstones could do as they pleased. “The effort and even most of the work toward the bill were pre-Airbnb even existing,” says Krueger. “And it was not done with any discussions with the hotel industry,” she adds, rolling her eyes, “because I’m constantly accused of shilling for the hotel industry.”

Not long after, Governor David Paterson signed the Illegal Hotel Law into being, rendering a huge number of Airbnb’s listings illegal.

The Airbnb founders were caught off guard. It wasn’t that they hadn’t anticipated resistance. All prophets face doubters. “We knew that any new technology, especially if it enters the real world, can be potentially misunderstood, especially by government,” says Chesky. “If you look at the history of so many technologies, starting with the automobile, there were so many rules, like that cars couldn’t be on the road because they would disturb the horses.”

They were a little hurt that the first wave of pushback came from New York, the place they’d identified as having their most dedicated users. “I’m from New York,” says Chesky. “I thought, New York’s going to love us. We thought people would be thanking us or at least there would be some gratitude for the thousands of people whose homes … We were way off, obviously.”

But did hurt feelings stop Steve Jobs? Did they stop Zuckerberg? Chesky and Gebbia resolved to fight the law. But because they didn’t know anything about law—they were art students, remember—they did what they’d done when confronting a challenging problem at RISD: They consulted experts. With their sizable budget, they soon amassed an impressive roster of politicos who were young enough to grasp their vision and experienced enough to, you know, know what to do. Among them were David Hantman, former chief of staff for Chuck Schumer; politically connected flack Risa Heller; and, in a particularly genius bit of casting, Bill Hyers, the mastermind behind the recent election of New York City mayor Bill de Blasio. Hyers had never lived in New York City before the mayoral race, but it didn’t take long for him to sniff out the source of the practically pheromonal angst that emanates from most of the city’s residents. “Everybody has some sort of anxiety about money here,” says Hyers. “You got 40 billionaires; 400,000 millionaires. That means there’s eight million people who have to live and work and survive in this city that’s very expensive.” He’s betting that the economically focused ads he designed will have a similar halo-producing effect for Airbnb. “If people like something and they speak out about it, that can be very effective,” he says.

Also joining the brain trust was Douglas Atkin, a branding Svengali who worked on the launch of JetBlue in his previous life as an advertising executive. “I’m the devil, actually,” Atkin told the audience this spring at a conference called “Share,” put on by one of the “grassroots” advocacy groups he founded as a new guru of the sharing economy. Atkin, who was hired as Airbnb’s head of community last year, is the author of a book called The Culting of Brands: Turn Your Customers Into True Believers, which describes how companies can generate cultlike devotion using techniques gleaned from actual cults—or, as he calls them, “radical belonging organizations.” Atkin’s hand is evident in Airbnb’s newly conceived tagline—“Belong anywhere”—and he’s been adept at whipping up the party faithful at host meet-ups he organizes. (“Successful cults which are turning into the next world religions, like the Mormons, know that personal interaction is the fastest route to cult growth,” is one Atkinism.) In videos from the meet-ups, people say things like, “In my life before Airbnb, I always felt really beholden to the company I worked for. And now I just feel really free.”

And: “I feel human again. I feel like myself.”And: “It unleashed this adventurer in me that I didn’t know existed.”

And: “I feel human again. I feel like myself.”And: “It unleashed this adventurer in me that I didn’t know existed.”

“Cults,” as anyone who reads Atkin’s book will find out, “make people feel more themselves.”

Airbnb would like to be seen as a cult of compassion, one in which taking 6 to 12 percent off the top of every transaction is secondary to a mission of economic empowerment and social responsibility. Which is one of the reasons it put out a video this summer reminding people of the tool it had created during Hurricane Sandy, which enabled members of the community to host victims for little or no money. “It was amazing to see after the storm people giving everything to strangers,” Shell, a host in Brooklyn, says in voice-over as the Airbnb logo comes up onscreen, telling users to “Text BELONG to get involved.” “You get to see the true spirit of New York.”

But if there is one thing we know about the True Spirit of New York, it is that she is a moody bitch. While some New Yorkers may have found the Sandy ad moving, others found themselves saying—with no disrespect to Shell, or the kind people who lent out their homes during the hurricane—“Does New York City need a smarmy sharing-economy start-up from San Fran–fucking–cisco to tell it about its true fucking spirit?” No, it does not.

New York–based tech blog Valleywag called the ad “cynical,” which it did not mean as a compliment; Gothamist called it “sinister” and then went further, arguing that despite the message of the PR blitz, Airbnb could actually make New York’s housing problem worse.

This is one of the most muddled aspects of the debate over Airbnb. The backbone of the company’s ad campaign is that it is making housing more affordable for people who want to live in New York, and that might in fact be the case for Carol and Bob and Shell and maybe even people you know: Sixty-two percent of New York hosts, Airbnb claims, are using the service to help pay their rent.*

And yet: Most of the company’s opponents are affordable-housing activists.

“Airbnb’s ad campaign is sneaky, and sneaky good,” says one of those activists, Jaron Benjamin of the Metropolitan Council on Housing. “One of the stories they presented talked about gentrification, a rapidly changing neighborhood and someone who didn’t have money worried about not being able to pay rent and being evicted … Then there’s this wonderful organization that came along and tried to help them! Airbnb!”

In reality, Benjamin says, property owners all over the city, having realized they can make more money on short-term rentals, have begun converting apartments into full-time Airbnb properties, resulting in their being taken off the market for full-time tenants and the further depletion of the already limited stock of affordable or even relatively affordable housing. “Oh, it’s definitely the way to go financially,” says my neighbor who owns a three-family building in Bed-Stuy. Possibly not unrelated: This past winter, the data-scraping company Connotate analyzed Airbnb’s site and found rent had risen precipitously in the areas with the highest concentration of listings, like Bed-Stuy and Harlem. This may be a coincidence, and certainly not every landlord has it in him to become an Airbnb hotelier, including my neighbor, who doesn’t want to change sheets all the time. But consider the experience of Chris Dannen, a 29-year-old webtrepreneur who was served with an eviction notice after a year of hosting Airbnb guests in his Greenpoint apartment. When he dropped off his final rent check, he noticed the management company was converting it into a hotel: The “loft suite” apartments are currently listed on Airbnb for $199. Dannen was, and still is, a believer in Airbnb’s cause. “I’m of the millennial view that it’s a nice way to meet people and make friends.” But he was disappointed in Airbnb’s reaction to his situation. “In retrospect, I would say, they knew this was going to happen to people, and they didn’t do anything to help me.”

It took Airbnb more than two years to put up a notice warning people that listing apartments may be against the law or their building regulations. Even after it did, a lot of people have simply ignored the warnings, either out of indifference to Terms and Conditions or loyalty to the cause. When I looked for Airbnb listings in my building in Bed-Stuy—it was easy to find them, as we all have the same old-timey light fixtures—there were five, all of which are illegal.

“Here is the thing,” says Tory, a 29-year-old part-time tutor and one of our building’s hosts, when we meet for a glass of wine in the building’s library, which I suddenly notice contains more than one well-thumbed copy of Let’s Go New York. “This has been like a thing for thousands—well, not thousands, for tens of years: People have had people just stay in their apartment through word-of-mouth. Like, ‘Yeah, we’re going to be away. Give me $100 for electricity.’ Now just because someone is formalizing it, they’re trying to make that illegal?” she adds indignantly. “I’m paying for ownership, temporary ownership over a space, and I can do with it what I please.”

*This article has been updated to clarify that 62% of New York hosts use Airbnb to help pay their rent, not 62% of New Yorkers.

One afternoon, I meet up with a friend of a friend, a European designer in his 40s we’ll call Rolf, since he doesn’t want his real name to be used because “it would be detrimental to the cause.” Rolf has three listings on Airbnb: one for the apartment where he currently lives, which he rents out while on vacation; a second for a condo he owns near the West Side Highway, which he’s currently subletting to a Russian oligarch who owes him money; and a third for the rent-controlled studio in the West Village he moved into with his then-girlfriend 20 years ago. Even though Rolf is now married to a different woman and has a family, the building’s owner still thinks he lives there with his ex. “And that we have a lot of relatives coming to stay,” he smirks.

Right now, where we’re living in Bed-Stuy, the possibility of our landlord’s seeing the success of these units on Airbnb and deciding to turn our building into a lucrative hostel for tourists seems pretty unlikely. But a couple of years ago the people in the affordable-housing units across the street probably wouldn’t have been able to imagine a building with old-timey lights and a gym going up in their front yard and probably didn’t think they would be, as activists outside their building put it recently, “the No. 1 target of developers.” When it comes to real estate, the Spirit of New York can also be a real asshole.

Rolf knows subletting a rent-controlled apartment is illegal, but he doesn’t feel any moral qualms about it. He’s been here long enough to know that if a real-estate loophole presents itself and you don’t jump through it, someone else will. He learned this when he first moved into his place in the Village, back in the ’90s. “The guy moving out was moving in with his girlfriend, who had a rent-controlled place on Park Avenue for like $500,” he says. “She was a lawyer.”

Rolf doesn’t use his real name on the site either, by the way. “I have fake name, fake address,” he boasts in his German accent. “Also my photo,” he says. “I search the internet and use an image of like a young, sporty guy. I want people to think like, Hey, friendly host.” This is why he prefers Airbnb over sites with more stringent requirements, like VRBO, where “I need to show that I’m the manager or the agent, I would have to show my lease.” If he had a little bit more liquidity, he says, he’d acquire even more apartments to use as Airbnbs. “Go ahead, have a drug-infested orgy,” he says magnanimously.

Rolf is the kind of person who gives Airbnb opponents the vapors. “This thing is just hell on wheels,” mutters Tom Cayler of the West Side Neighborhood Alliance. “It’s a scourge, the whole phenomenon: Airbnb, Flipkey, Homeaway, Stayonmyface … They’re incentivizing taking a whole class of apartments off the market. And I don’t see the upside of giving up an entire class of residential apartment buildings so that a couple of guys can become billionaires.”

Like most of Airbnb’s opponents, Cayler, who lives in a rent-controlled apartment near Times Square, sees Airbnb as another force majeure coming to sweep away what remains of his New York, the old New York, the good New York. And no amount of marketing can convince him that Chesky and Gebbia could be just a couple of well-meaning former art-school students with an interesting idea about shared living spaces. “Do you know why they are pushing so hard on this?” he bellows. “It’s called IPO. Initial public offering. This is not the sharing economy. This is the ‘me me me, I need to make my IPO as high as possible’ economy. And they are willing to destroy this entire city to do that.”

“Well, that’s not … that isn’t allowed,” Brian Chesky says when I tell him about Rolf’s fake name and trifecta of apartments. “We’re cracking down on a lot of that behavior … The vast majority of people are renting the houses or the homes they live in.” Airbnb’s position is that it has not and will not have an effect on affordable housing. “There was a study …” says Chesky.

People at Airbnb refer to this study a lot. It’s by UC Berkeley professor Ken Rosen, who reported that home sharing by companies like Airbnb has had no effect on the housing market and, further, that it “has the potential to make urban housing more affordable for more families.”

“But you guys commissioned that study,” I say.

“Okay,” Chesky says sulkily. “So then we said other people should do it, and then they haven’t done it. So the only study we know about is the one we did.”

Adolescent company that it is, Airbnb can be a little irritable. A little sensitive. Like when the New York attorney general’s office asked it for data on its customers earlier this year and Airbnb freaked out, as if it were really out of line for them to be asking for information about the multibillion-dollar corporation that was operating largely unregulated in its own backyard.

“This is a wrongheaded waste of time and law-enforcement resources,” David Hantman fumed on the company’s public-policy blog, going on to suggest that the attorney general, under pressure from the powerful hotel lobby, might soon roust Airbnb hosts and their nightcap-wearing Belgian guests from their apartments and drag them through the streets in chains. “If you’re one of the thousands of New Yorkers who has ever rented out your place while you were away for a weekend,” he wrote, “the attorney general wants to know who you are and where you live.”

In The Culting of Brands, Atkin refers to this as “Demonizing the Other”: “Real or imaginary, identifying an enemy and dramatizing a threat will galvanize the community’s sense of separation, unity, and identity.”

Any opposing viewpoints are attributed to ulterior motives. “It’s a very aggressive posture for a government to take, don’t you think?” says Hantman over lunch in Tribeca. “Of all the things in the world, why is sharing your home so bad? It’s a little suspicious, if you ask me. We know it cannot just be for public-policy reasons. There have to be other reasons.” He says this meaningfully. “I don’t know what they are.”

Even after the office of the attorney general amended its request to ask for data on only the top 124 hosts in New York, the company insinuated that anyone could be next. “Without knowing more about why the attorney general is interested in those hosts specifically, it is hard to know why they have been targeted,” Hantman wrote on Airbnb’s blog.

“That is so disingenuous,” says a spokesman for the AG’s office. “We’ve said publicly, over and over again, that we are looking for illegal-hotel operators.” That group of people, he points out, has collectively made $60 million on their apartments over the past three years. The average power-hoster is making almost $500,000 a year, and the least prolific among them controls about ten different apartments. “So, hardly trying to make ends meet.”

Airbnb maintains it has no problem with regulation. It even offered to pay—or rather, have hosts pay—the same taxes levied on hotels, although the offer was initially rebuffed. “Because it would legitimize our business model!” says Hantman. But the company has thus far resisted installing, say, an algorithm that would block people from listing multiple apartments. “Some cities want property groups” listing multiple apartments, explains Chesky. When the company quietly deleted some 2,000 listings belonging to what looked like illegal hotels the day before an April court date with the attorney general, it was because they were bad hosts, according to Chesky. “We weren’t aware of how many property groups there are in New York,” he says. “When it was brought to our attention, we started looking at it and we realized, actually, these people all provided bad experiences and get a lot of customer complaints. We said, ‘You know what? These people, what they’re doing, we don’t stand for.’ So we removed them.” This might not be a great long-term strategy.

Not long ago, a video ad for an Airbnb property made the rounds on tech blogs. “If you are interested in meeting people who are amazing and very kind, then you might be interested in this place,” the host said, as his camera shakily passed through 22 bunk beds in a two-bedroom apartment.

It had two positive reviews: “Very nice place to stay at and met a lot of wonderful people!” read one.

At rare moments, Airbnb admits there might be some flies in the ointment. “It’s a start-up,” says Hantman. “As you grow, there’s some point at which you no longer know all of your customers. There are issues we have to address. But this knee-jerk reaction of, ‘Oh my gosh, this seems new, we need to stop it, because we don’t understand it’ … Most people want this. The only people who don’t are older. People who have less experience with technology and innovation and just like things the way they are.”

“Right, right, we are the outdated institutions who need to catch up with the times,” says a person in the attorney general’s office, who doesn’t want to be named for fear of seeming “against tech.” “This has happened with a number of Silicon Valley companies. They come in thinking they don’t have to follow local laws because they’re from the internet.” In Silicon Valley, where The Future is revered above everything, it isn’t considered breathtakingly rude to call someone old and out of touch to their face, or to brush off their real-world concerns, or otherwise deem their lives irrelevant.

Tom Cayler, born 1950, scoffs. “Just because something is the new thing doesn’t make it be ‘This is what we should do.’ You know who else was called the new wave? Hitler was called the new wave.”

Wait, what were we talking about again? Oh, right, a website founded by a couple of art students that makes it easy to book short-term stays in people’s homes.

After Labor Day, Airbnb agreed to turn over the listings of its top users to the attorney general. A fresh set of posters went up in the subway, and for a little while, it seemed like cooler heads might prevail. “We like cities,” Chesky tells me. “We want to help cities. We don’t want to be the marshmallow man.” But once you conjure the monster, it’s not so easy to put it back. Following the news of Airbnb’s announcement, a group of Airbnb hosts filed suit to stop the company from giving their information to the attorney general. “They’re traitors,” their lawyer bellowed in the Post. The group, made up of the people, you recall, who allegedly made an average of $500,000 a year on Airbnb, called themselves New Yorkers Making Ends Meet in the Sharing Economy.

Then, in early September, a group of protesters gathered on the steps of City Hall. “I have to call you back,” said the spokesman for Airbnb when I called him to ask a question. “We’re at a protest of people who really hate us!” He sounded giddy.

The group was called ShareBetter, and it had all of the usual suspects: Tom Cayler, Liz Krueger, Jaron Benjamin, Dick Gottfried. The Airbnbers stood off to the side, demarcated by their button-downs and pricey sneakers. Afterward, ShareBetter would release a parody video of an Airbnb ad, the high quality and the content of which made it seem like the group might be well funded by … “the hotel industry,” as Airbnb wrote triumphantly in a blog post.

The fight was back on, even though it was clearly a fight that no one would ever win. No one, not the rich, not the poor, not the millennials or the old people, ever gets to live in their perfect version of New York. But as I looked at all of them, hustling and sniping and backbiting and hair-pulling and garment-rending and agitating, it was clear: The Spirit of New York was very much alive.