Three years ago, Adam Driver was a former Marine with little more than a degree from Juilliard and a guest spot on Law & Order to show for his acting career. Then he landed on a show called Girls.Appealingly intense and compellingly awkward, he was nobody’s idea of the next Brad Pitt. Now, suddenly, Hollywood is betting he’s something better than that: his generation’s cure for the cookie-cutter leading man

This is very cool,” Adam Driver says as the serene face of the Statue of Liberty comes into view. We levitate around it for a little while, observing the trails of tourists that scurry, antlike, under Lady Liberty’s skirt. The air is smooth and clear—just as our helicopter pilot promised. Then: “Shiiiit!” Driver says, as the machine shudders and dips, then jokingly throws out his arms as though bracing himself against potential disaster. The gust lasts approximately two seconds. The pilot glances back quizzically at this strange tall man with the slightly familiar face. Driver pushes back his longish hair—the indie-rock styling of which may not be so much his as that of the character he plays on HBO’s Girls—and nods. “I’m glad they gave us these fanny packs,” he deadpans, patting the life preserver on his waist.

There’s not much Adam Driver is afraid of, certainly not a touristy helicopter trip. “We rode in helicopters in the Marines,” he told me on the tarmac. “Also, we’ve been using them a lot in this movie I’m in.” He sounded a little embarrassed, like being in a movie is so much less cool than being a Marine. But it was, after all, his second choice of career.

These days it’s rare to encounter an emerging Hollywood talent who is also a veteran—of a Who Wore It Best battle, maybe, but not the actual military. But before Driver became the breakout star of a show about entitled slackers in Brooklyn, he served in the armed forces. More specifically, he was “a fucking Marine who went to Juilliard,” as one director put it, in that tone of curiosity and awe Driver tends to inspire.

The helicopter arcs over the Brooklyn Bridge. “There’s my apartment,” Driver says, pointing. He sounds a bit wistful, probably because lately he hasn’t seen the inside of it much. Over the past couple of years, Driver has been in the midst of a transformation, from the most unexpected star of a cult TV show to being “probably one of the most sought-after actors around,” says director Shawn Levy, who moved heaven and earth—in the form of the schedules of Jason Bateman and Tina Fey—to cast Driver in the role of the perpetually adolescent younger brother in this month’s This Is Where I Leave You. The movie is the first in a veritable avalanche of prominent films Driver will soon appear in, among them Jeff Nichols’s Midnight Special, Noah Baumbach’s While We’re Young, and Martin Scorsese’sSilence. Like a cool band, he’s been plucked from hipster Brooklyn and is in the process of being fully mainstreamed, though he still retains his cred: Last night, he was up late shooting scenes for the fourth season of Girls, even though today he’s leaving for the London set of the latest installment in that blockbuster of blockbusters, Star Wars. I’m looking at him craning his neck toward the chopper window, this quiet, slightly goofy guy whose Adam’s apple, in profile, sticks out roughly as much as his nose, and Driver doesn’t seem like the world’s most likely movie star. But “this kid,” Levy says, with mark-my-words import, “is going to be one of the most formidable actors of his generation.”

“That’s nice of Shawn,” Driver says when I tell him what Levy said. “He’s, like, the kind of person who believes things will turn out good. Unlike me, who believes things are going to go to shit at any minute.”

A week or so before our helicopter trip, we met for lunch in Manhattan. From the moment we walked in, it was clear that the place, with its white tablecloths and overly attentive waiters, was all wrong for Driver, his sensibility as well as his size—not that Driver, a polite midwesterner, would ever complain. Wearing jeans and a T-shirt, he folded his six-foot-three body into one of the froofy chairs, ordered a steak, medium-rare, and didn’t even blink when it arrived covered in edible flowers. “My plan was to be able to make a living as an actor,” he says. “And then everything else just…” He motions with one of his hands and nearly smacks a water pitcher out of the grasp of a lurking waiter. “Oh no!” he says, hunching his wide shoulders forward in shame, like he’s the Incredible Hulk and has just burst out of his clothes in public.

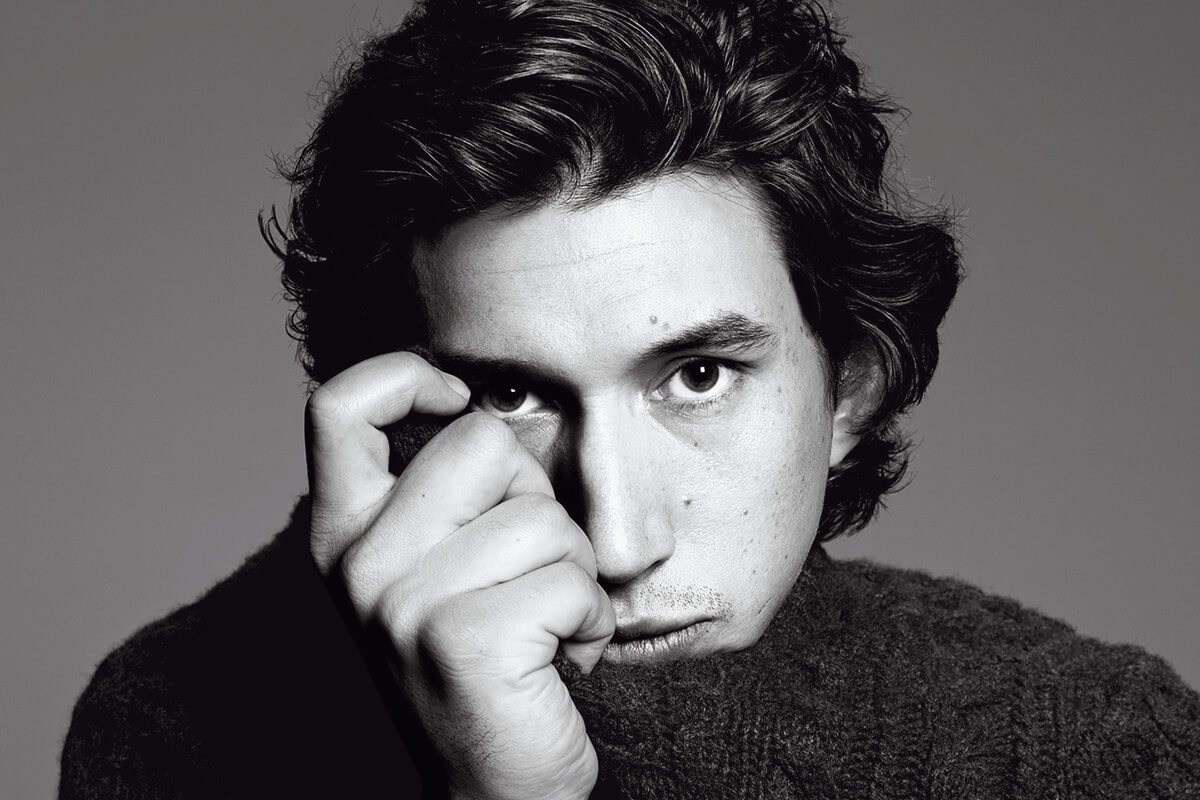

Which is kind of a fitting image to show what happened to Driver. As the lovable sexual deviant Adam Sackler, he burst, partially and sometimes fully naked, onto the screen in Girls,playing the boyfriend of Lena Dunham’s character, immediately commanding attention. It’s hard to say what was most compelling about him: perhaps his face, with all of its different planes, like a carving from Easter Island. Or maybe his incongruously muscular body, which seemed to contain equal amounts of twitchy intensity and feral grace. Or it could be the way he spoke, forcefully but always with a tremulous undercurrent of feeling that somehow made him endearing, even as he barked out fantasies to Dunham’s character while having sex: “You’re a junkie and you’re only 11 and you had your fucking Cabbage Patch lunchbox. You’re a dirty little whore, and I’m going to send you home to your parents covered in cum.”

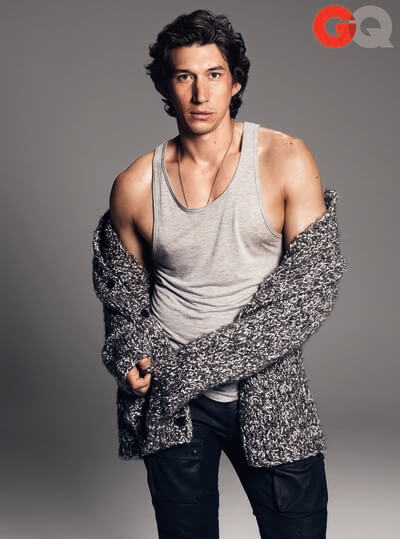

“To me, Girls announced this wholly new and surprising kind of actor,” says Levy, who came away from his initial coffee date with Driver with what sounds like a full-blown man crush. “The way he moves, talks, eats, navigates the world,” he gushes. “It’s really authentic. Adam is a fucking man.”

At a time when nearly every industry is trying to commodify authenticity—McDonald’s artisan burger, anyone?—Hollywood has lagged. To Levy and others, Driver is a welcome course correction from the parade of blue-eyed Brad Pitt types (your Chris Hemsworths, your Chris Pines). His ripped physique is comparable to today’s action heroes’, but beneath his pecs there is the suggestion of a brain, a heart, a soul. Driver’s electric intensity and his intriguing backstory suggest that this is a man who has Seen Things. “He’s a real person,” says Baumbach.

Adam Driver, real person, grew up in the Leave It to Beaver-ish town of Mishawaka, Indiana. His family were devout Baptists—his stepfather was a preacher—though Driver was a bit of a rebel. He sang in the choir, but he also ran a fight club, where he and his friends would beat one another in a field behind a banquet hall that hosted weddings and baby showers. “Can we just…,” he interjects apologetically when I start to ask about how his parents feel about the path he’s chosen, “if I can, I’ll skip the parents stuff?” He doesn’t want to reopen any family wounds. “We have different views on the world,” he explains. “They have their life; I have mine.” He didn’t tell them about Girls until after the second season. “What was I going to tell them?” he says, laughing. “I just masturbated on some girl’s chest”?

Driver’s parents didn’t know much about his acting in high school, either—not that it was all that important then. Appearing in a production of Oklahoma! just seemed like a good way to meet girls. But it’s indicative of his tendency toward extremes that once he began considering it as a career, he saw only two paths available. “It was like the South Bend Civic Theatre,” he says with distaste, “or Juilliard.” He applied to the latter and didn’t get in. And that, for a while, was that.

On September 11, 2001, Driver was almost 18 years old, living in an apartment in the back of his parents’ home and “not doing fucking anything,” he says. In the swell of patriotism that followed the terrorist attacks, he decided to enlist in the armed forces. “It just seemed like a badass thing to do,” he says, “to go and shoot machine guns and serve your country. Coupled with: ’There’s nothing for me here, there’s nothing that’s keeping me here, there’s nothing that’s stopping me from going.’ ” He was shipped off to Camp Pendleton in California.

On September 11, 2001, Driver was almost 18 years old, living in an apartment in the back of his parents’ home and “not doing fucking anything,” he says. In the swell of patriotism that followed the terrorist attacks, he decided to enlist in the armed forces. “It just seemed like a badass thing to do,” he says, “to go and shoot machine guns and serve your country. Coupled with: ’There’s nothing for me here, there’s nothing that’s keeping me here, there’s nothing that’s stopping me from going.’ ” He was shipped off to Camp Pendleton in California.

Rarely do you hear praise for the brutal initiation of basic training, but Driver loved it: “You see what your body can do and how discipline is effective.” He fell comfortably into the structure of the military and into friendships with the people he met there. “It’s hard to describe,” he says. “You’re put in these very heightened circumstances, and you learn a lot about who people are at the core, I think. You end up having this very intimate relationship where you would, like, die for these people.”

Driver never made it to war. Two years in, he broke his sternum on a cheapo mountain bike and soon after was medically discharged, an outcome that still “fuckin’ kills me,” he says. “To not get to go with that group of people I had been training with was…painful.”

He moved back to Indiana, but he was restless and depressed. “I wanted a challenge,” he says. Driver’s thoughts wandered again to Juilliard. “The Marine Corps is supposed to be the toughest and most rigorous of its class,” he says. And in a similar way, Juilliard was the toughest in its class. “Obviously the stakes are different,” he says. “You have the risk of getting shot or killed in one and just embarrassed in the other. I thought, ’This will be easy.’ ” He was working as a security guard at a warehouse in Mishawaka when he heard he’d been accepted.

To make going to school in New York City even more of a challenge, Driver devised a militaristic routine for personal and intellectual growth. “I wanted to make it extreme,” he says. To stay fit, he’d run from his apartment in Queens to the school’s Manhattan campus. He’d often start his day with six eggs and later prepare and consume an entire chicken. Nights he spent binge-watching classic movies or at the library reading plays. Since he’d been a lousy student and grew up sheltered from a lot of secular art and music, “I felt like I was behind,” he says.

To most of Driver’s classmates, he was an oddity. He didn’t have much patience for them, either. “I think he thought other people weren’t as committed,” says Richard Feldman, a professor at Juilliard. “I made a lot of people cry,” says Driver regretfully. At the same time, he was drifting apart from his friends in the Marines. “We all got together in Texas; a friend of ours had passed away,” Driver says. “And I was trying to explain to them what I was doing at Juilliard. And I’m like, ’Yeah, we wear pajamas, and we talk about our inner colors, and there was this ercise where we all gave birth to ourselves…’ And they’re like, ’What the fuck are youdoing?’ ”

There’s Governors Island,” Driver says, pointing from the helicopter, launching into an anecdote about a friend from Juilliard who spent a sweaty afternoon in period dress churning butter for a historical-reenactment gig.

Though Driver’s first big reenactment gig, on the other hand, would come opposite Daniel Day-Lewis in Lincoln, success wasn’t exactly immediate for Driver in the years after college. He did a few Off-Broadway plays, the obligatory Law & Order episode, a couple of easily missed movies. After Lincoln came a small but charming part in the Coen brothers’ Inside Llewyn Davis, and of course Girls, and before he knew it, he was getting calls from Martin Scorsese and posing shirtless with a live sheep draped over his shoulders forVogue.

“It’s very nice,” he says, cringing like he did before, like he’s embarrassed both by his success and for complaining about it.”But in a way, I don’t feel like I’ve really put in my dues. Like it doesn’t feel earned.” Driver puts a premium on things that take a lot of work. It’s one reason he hates the Internet. “Not to get on, like, a stomping pedestal about the culture or anything,” he tells me at one point. “But everyone is so used to having everything immediately, and that doesn’t seem to lend itself to things being good. You know? The things on there, they’re just mediocre. There’s not really a lot of work or weight involved.”

Driver applies the discipline acquired in the military to everything he does, from the quotidian details of existence to his work. “I think it’s good to live an artful life,” he says, sipping a pink smoothie in the Brooklyn café we’ve safely landed in after our helicopter ride. “I like everything I do to have some kind of meaning.” To attain something worthwhile, one must experience a certain amount of suffering: “The more masochistic the part, the more appealing.” When it comes to his work, he can get a little obsessive—which is why he never actually watches himself on-screen. He decided to stop after Lena Dunham invited him over to her parents’ apartment in Tribeca to watch the pilot of Girls. “I just saw all the things I wanted to change or make better,” he says. “And I worried from then on I would just be thinking about how it looks as opposed to what’s happening, and that’s, like, not a good way to work, because after a while it’s a little bit masturbatory.”

Driver knows that talking about Acting is a good way to sound like “a pretentious fucking asshole,” he says. But he does have lofty ideas about The Craft. “He’s one of those actors,” says Baumbach, who watched him on the set of While We’re Young. “Like they became the part, you couldn’t get them out of it, nobody could look him in the eye…” He doesn’t mean this in a look-out-gaffers-here-comes-the-next-Christian-Bale way. “He’s not a brooder,” Baumbach says. “But it’s important to him.”

Back when he was at Juilliard, in one of his learning jags, Driver came across Ajax, the fifth-century Greek tragedy about a soldier who, slighted by his superiors, erupts in a blind fury and decides to kill them all. “It’s a play about someone who suffers from PTSD,” he says. At the time, Driver was suffering from his own far milder version of PTSD, in the form of the guilt he felt about leaving the military. “Like, I dropped the ball and got out and then became a fuckin’ actor,” he says. The play gave him an idea about how to reconcile those feelings and give what he was doing at Juilliard some meaning.

With the help of the school and Joanne Tucker, his classmate turned girlfriend, Driver founded Arts in the Armed Forces, an organization he still runs, which deploys actors to perform at military bases. When he was in the service, “they were always trying to bring in, like, the Dallas cheerleaders,” he says. “And I love cheerleaders. I could watch cheerleaders all day long. But I felt like the military could handle something a little more thought-provoking.” They decided on simple, relatable monologues about the human experience. “When I think of my military experience, I don’t think of the drills and discipline and pain,” says Driver. “I think of these, like, really intimate, human moments of people wanting to go AWOL because they missed their wives, or someone’s dead and they can’t deal with it. And that’s what I wanted to show.”

With the help of the school and Joanne Tucker, his classmate turned girlfriend, Driver founded Arts in the Armed Forces, an organization he still runs, which deploys actors to perform at military bases. When he was in the service, “they were always trying to bring in, like, the Dallas cheerleaders,” he says. “And I love cheerleaders. I could watch cheerleaders all day long. But I felt like the military could handle something a little more thought-provoking.” They decided on simple, relatable monologues about the human experience. “When I think of my military experience, I don’t think of the drills and discipline and pain,” says Driver. “I think of these, like, really intimate, human moments of people wanting to go AWOL because they missed their wives, or someone’s dead and they can’t deal with it. And that’s what I wanted to show.”

After the group’s first performance, at his old training camp, Driver received more than a few slaps on the back from the troops. “They were like, ’Fuckin’ loved it, bro,’ ” he says, affecting a macho voice.

Someone once described acting to Driver as a service, and it stuck with him. “That made sense to me,” he says. Even now, “in the midst of all this fuckin’…you know, take pictures with a sheep on my shoulder,” he still feels this way. “Here’s the thing,” he says, and pauses to take a bite of a hamburger. “Life’s shitty, and we’re all gonna die. You have friends, and they die. You have a disease, someone you care about has a disease, Wall Street people are scamming everyone, the poor get poorer, the rich get richer. That’s what we’re surrounded by all the time. We don’t understand why we’re here, no one’s giving us an answer, religion is vague, your parents can’t help because they’re just people, and it’s all terrible, and there’s no meaning to anything. What a terrible thing to process! Every. Day. And then you go to sleep. But then sometimes,” he says, leaning forward, “things can suspend themselves for like a minute, and then every once in a while there’s something where you find a connection.”

It may not be the same as wasting terrorists, but it’s something. “It’s a good, hard responsibility,” he says, crinkling up his napkin. “Maybe that’s self-indulgent, that I think I can really do something. But the potential is there.”

Adam Driver is nothing if not up for a challenge. Now he stands. He has to go meet Joanne, who’s joining him as he heads back to the Star Wars set in London. Last summer they got married. Driver’s parents were at the wedding, circulating among the Juilliard people. He still doesn’t talk to them about what he does, but he knows they’re proud. The feedback from his friends in the Marines has been a little more direct. “They were like, ’So, I saw your fuckin’ show,’ ” Driver says in his bro-y voice. ” ’And you’re fuckin’ naked a lot. So, okay. Tell me when the next thing comes out.’ “