With his turn as the eponymous character in this month’s The Lone Ranger, Armie Hammer is primed for Hollywood’s A-list

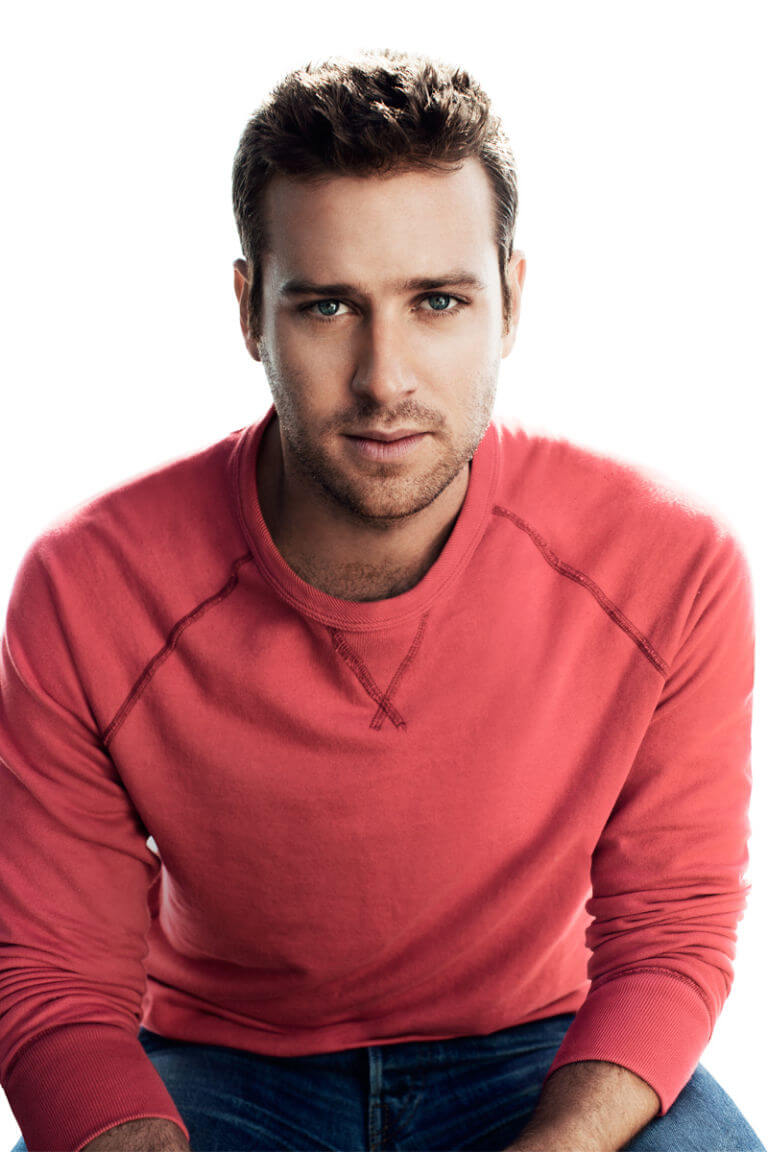

“Hi, are you…?” inquires a baritone voice from above. When I look up from my seat to see Armie Hammer leaning over me, well, let’s just say I now understand what it means to swoon. Not just because he is, impossibly, 40 minutes early for our lunch date, or because herecognized me, having taken the unprecedented step of googling his interviewer, but because there might not be another man whose physical description is so worthy of romance-novel clichés. Six-foot-five, with shoulders that can only be described as strapping, Hammer has smooth, golden skin and eyes the color of the Pacific Ocean. On this cool spring day, his flaxen hair is windswept, and his ridiculously chiseled jawline is dotted with stubble—the first sign that behind his polite, aristocratic veneer lurks a wildness.

Earlier, Hammer’s publicist had told me the 26-year-old would be “most comfortable” here, at the restaurant of the Sunset Marquis, in West Hollywood, but as he tosses his motorcycle helmet into the booth, happily chattering about the ride over on his Vespa (“I mean, it’s about as badass as you can be while still riding a scooter”), a substitute for the motorcycle he dearly wants but that his wife of three years, Elizabeth Chambers, won’t let him buy, it becomes obvious that this was a lie. Armie Hammer is not some Hollywood prig who feels at ease only in a designer hotel. He is a man, or, at least, a large, golden-retriever-like man-boy, who seems to be having some trouble fitting his long legs in even this oversize booth.

I’d read that Hammer grew up shooting in Texas (“It was a family activity kind of thing—go out and shoot a bunch of cactuses,” he explains), so I suggest skipping lunch and heading to the nearest gun range. “Fuck yeah!” he says, scrolling through his iPhone, trying to find one nearby. “My favorite is next to the Angeles National Forest. You can do things like throw a watermelon in the air and shoot it.” Hammer is a gun enthusiast—he bought his first rifle at 18—and he puts his hobby to use as the title character in this month’s The Lone Ranger, but he’s sensitive to the current debate surrounding the weapons. “I’m definitely for responsibility,” he says, pausing in his search. “I don’t think Obama is trying to take our guns, and I don’t think we have to fight the government to keep them. If you want to go out for a hunting trip and shoot cans with your son and a .22, that’s fine. Do I need an AK-47 with a 100-round magazine if I’m going on a hunting trip? No. It is, to borrow a phrase from Confucius, like using a cannon to kill a mosquito. Having just made a Western, though,” he says, breaking into a grin, “it’s fun to have a gun on your hip. You’re like, ‘This is an extension of my manhood.’?”

He resumes his search, but alas, the closest range doesn’t open till three, two hours from now, and Hammer has to meet someone at four. “Damn it! That would have been so fun,” he says. “I do like this place, though. I used to come to the Whiskey Bar all the time and get shitfaced. It’s the best. You’re sitting there drinking and next to you is, like, Steven Tyler.” His eyes light up. Idea? Alas, the bar doesn’t open till 8 p.m., the waiter tells us. Acceptance settling in, Hammer orders a steak, rare.

The actor is of almost atavistically manly pursuits. He owns a collection of vintage Olivetti typewriters, hopes to one day open a cigar factory, and amuses himself on movie sets by reading books on knots. Knots! “I love knots,” he declares as he slices into his steak.

“Armie’s a rare find,” says The Lone Ranger director Gore Verbinski. “He is in a sense…out of time. I felt this way the first time I met him. Like visiting a young version of an old, old, friend.”

Hammer’s portrayal of the Winklevoss twins in 2010’s The Social Network so thoroughly charmed audiences that the actual twins, who are much less charismatic, have gotten famous as a result. But since that movie, he’s maintained a relatively low profile, with only two films in the past three years: J. Edgar, in which he covered his face in liver spots and wrinkles to play Leonardo DiCaprio’s gay lover, and the Snow White redo Mirror Mirror, in which he played Prince Alcott. That should change after the release of The Lone Ranger, a $250 million summer blockbuster in which Johnny Depp plays sidekick to Hammer; just this morning, in anticipation of the movie, one industry group christened him the “male star of tomorrow.”

Hammer didn’t take the part just to see his name in lights, though. “I love an adventure movie,” he says, with boyish enthusiasm. “A guy who is faced with a problem and he has to deal with it, and then there’s the adventure—the hero’s journey, to borrow a term from Joseph Campbell. Like Moby-Dick. Fucking Ishmael!” Hammer is in the process of starting a production company and hopes to secure the rights to the life of John Fairfax, a British adventurer who rowed across the Pacific Ocean, whom Hammer first learned of after reading his obituary in The New York Times. “Everybody’s got a little of that in them, where you just can’t sit still.”

Hammer would know. During the filming of The Lone Ranger in Moab, Utah, he spent his weekends off with the crew, rock climbing or cliff jumping or renting four-wheelers, he says, to “just tear up mountains.” And once, while in Australia, “this homeless guy tried to stab me. I punched him and stole his knife.”

Wait. You punched a homeless guy and stole his knife? I ask.

“He started it.” The guy had mistaken Hammer for a person who owed him money, and started swinging his knife. “I was full of piss and hubris, and was like ‘Fuck you,’?” he says, mock punching the air. “I took his knife. Because he would have tried to stab somebody else! He was obviously crazy.

“My wife says I have a frontal lobe issue. Your frontal lobe controls your danger response, like, ‘Whoa, I shouldn’t be doing this.’ But she says it’s okay, because your frontal lobe doesn’t fully develop until around 30, so I have until then to get all this shit out of my system and then I need to calm down.”

Despite all that adrenaline chasing, Armie Hammer is no ordinary bro. (The references to works of literature and philosophers may be the first clue.) He’s Armand Hammer the second, named for his great-grandfather, who was the longtime chairman of oil company Occidental Petroleum Corporation—not the baking soda, though he did eventually sit on that company’s board. (“My great-grandfather wanted to buy it,” Hammer says, “because he thought it was funny that they named their baking soda Arm & Hammer. They were like, ‘No thanks, it’s not for sale.’ But later, when they went public, he ended up buying a bunch of shares and was like, ‘Ha-ha I have your company now.’?”)

Hammer grew up mainly in Los Angeles (with a few years spent in Texas and the Cayman Islands), attending private schools, but even though he had a face for high society, he had the soul of a rebel: One high school kicked him out after he wrote his name in lighter fluid on the lawn and set it on fire. And he resisted his parents’ pressure to go to college. “I didn’t care about college,” he says. “I knew I wanted to make movies.” Fine, they said, but he’d have to support himself.

Fortunately, Hammer started getting work right away, though just bit parts in movies and TV shows such as Gossip Girl. “Usually my character was called something like ‘Jock #4’ or ‘Abercrombie Boy.’?” At first he was distracted by the L.A. party scene. “It was like a—” He pauses, for a brief moment visibly uncomfortable. “I picture my grandparents reading this article,” he explains before continuing. “I’d grown up in a household of so much love and so much good, everything just felt wholesome. Once I was on my own, I was like, Let’s see how hot this candle can burn.” For three or four years, there were drugs and drinking and staying up for days on end and a lot of girls who were, in his estimation, “bad, bad news.”

“One chick tried to stab me when we were having sex. I should so not be telling this story,” he says—then does so anyway. “She was like, ‘True love leaves scars. You don’t have any.’ And then she tried to stab me with a butcher knife. Of course I promptly broke up with her,” he says. “Seven months later.”

“I called him Bruce Wayne,” says friend Joe Manganiello, who, despite a nearly 10-year age difference, instantly bonded with Hammer after meeting him in an acting class; the pair formed an unofficial support system and Tall Actors of Hollywood club. “He was smart, he was well-spoken, and he drove around in crazy race cars that resembled Batmobiles.” When Manganiello was cast in True Blood, he celebrated by buying Hammer a steak. Not long afterward, Hammer returned the favor when he landed The Social Network.

Hammer didn’t take advantage of the celebrity that came with the movie the way a lot of 24-year-olds might have. Instead, he married Chambers, a TV journalist and former model whom he started dating in 2008. Chambers had been seeing someone else, but the couple was unhappy, and one night when she came over with friends, Hammer made his move with a prepared speech. “I was like, ‘You have to break up with your boyfriend because we have to start dating.’?Her mouth kind of fell open. I said, ‘You were made for me,’ and she got this look on her face like”—Hammer launches into a girl’s voice—”?’Don’t you even.’?” He laughs. “I was like, ‘Wait, wait! And I was made for you. We were made to be together. So we can do this 30 years from now, when I’ve gotten married a couple of times and you’ve gotten married a couple of times, or we can start now and end up 60 years from now sitting on a porch in rocking chairs, talking about how good an adventure the whole thing was.’?”

Clearly, the speech worked. “I like the idea of marriage. I like the idea that I have a best friend,” he says, twisting the ring on his finger. “It’s just really comforting. I remember being single and trying to date, and it was just stressful and hard. It wasn’t fun. This is fun. I mean, not to be graphic,” he says, lowering his voice, ostensibly so his grandparents can’t hear, “but you can have sex and in the middle just start laughing about something totally funny. You can’t do that with someone you’re dating; you’re too nervous.”

When it comes to his wife, Hammer is an unapologetic romantic. “I have no qualms about kissing her in public. I know some guys are like, ‘Stop, there’s people around,’?” he says. “There’s such a big part of our culture, the male psyche—you don’t cry, you don’t show weakness. I mean, guys are just as emotionally complicated as women. We just play dumb better.” He readily calls Chambers his “soul mate.” “I don’t mean it in a cheesy way, but just like that connection, you just get it.”

Given his family’s notable wealth (they founded the Hammer Museum across town, whose permanent collection includes works by Van Gogh and Cézanne), it’s easy to assume that there’s a sizable trust fund that Hammer can tap into whenever he wants, but he insists his parents have never given him a large sum of money, nor has he asked for it. “For a while in our marriage, it was pretty tight,” he says. “And we liked that. We like living sort of hand-to-mouth. It makes you appreciate the time when you don’t have to live like that. We didn’t want to go to my parents and tuck our tails between our legs and be like, ‘Can you help us?’ We wanted to be our own adults.”

The sincerity with which he delivers this spiel makes it impossible for me to roll my eyes. Still, I can’t quite believe it when he says that money is another reason he hasn’t bought a motorcycle. “There was once another Hammer, by the name of MC, who spent all of his money really quickly, and I would like to avoid that.”

But you’re the male movie star of tomorrow! I say.

“But I’m not the male movie star of today,” he rejoins.

Hammer is taking a “strategic break” from acting, he says, making air quotes, which is another way of saying he hasn’t found a job he wants to take. “There are offers,” he admits. “But they’re the kind of offers that are like, ‘We gotta get him, that movie is coming out, offer him a part in the movie.’ And it’s like, ‘You want me to play a 46-year-old Hispanic male? That doesn’t seem right.’?”

When it comes to his career, Hammer is unusually restrained, as evidenced by the brevity of his résumé. He is wary of the traps he, as a member of the Twilight generation, might fall into. “I’m not crazy about taking my shirt off for a movie,” he says. “Right now, that’s the thing: You have a young, handsome actor, take his shirt off, put him in front of the camera. It sets up this pressure to stay camera ready all the time. I don’t want to think about myself that much. The guys who do it are like, ‘Oh, it’s been two hours, I have to eat yams. My glycemic index is dropping.’ It can very easily turn people into narcissists. It just seems silly.”

He’d rather not act at all than act in the wrong movie. “A lot of people don’t understand the hours that go into making a movie. It’s 18 hours on your feet, doing shit, and then you get a couple of hours of sleep and you wake up and do it again. But it feels good,” he stresses. “I love this way too much to turn it into work.”

In the meantime, he and Chambers have opened a bakery, Bird, in Chambers’ hometown of San Antonio, for which they have “big plans slash delusions of grandeur,” like maybe franchising it. At the time we meet, the only big role in his future is that of grand marshal of San Antonio’s Battle of Flowers Parade. “I’m just waiting to find the right thing,” he explains. “That’s what I have found every step of the way: Choose the right project for the right reason.” A few weeks later, the right project comes along: the Guy Ritchie film adaptation of The Man From U.N.C.L.E., in which Hammer is slated to play a secret agent alongside Tom Cruise.

The check arrives. Hammer goes for it, but I get there first. “This goes against all my chivalrous instincts,” he says, blushing a little. “But thank you.”

Outside by his scooter, Hammer shows me one of the knots he invented. This one begins with a basic slipknot but has a neat half-hitch at the end. “I wanted to start with something classic,” he says, “but then there’s a little twist to it.” As a metaphor for his personality, it’s not bad.

Hammer gives me a hug. It feels a bit like being enveloped by a bag of warm rocks. Down in the valley, the sun has been getting huge and glowy, infusing the streets with a warm light, and by the time he starts his bike and waves goodbye, the male star of tomorrow is literally riding off into the sunset. On his scooter. For now.