After the crash, financier Ken Starr was revealed to be one of the greatest hustlers of our time. But he had nothing on his fourth wife, Diane Passage.

The Grand Havana Room is good, if you can get past the doorman. The Oak Room at the Plaza is the easiest game in town; just go early in the week, like on a Tuesday night, because later it fills up with tourists and C.P.A.’s from New Jersey. Wednesdays, Jean Georges draws an affluent after-work crowd; a girl who knows what she’s doing can easily get a free dinner along with her drinks. In fact, if you’re looking for a man who likes to visibly spread it around, pretty much all of the Vongerichten properties are a good bet, though if you prefer a long-term arrangement with a wealthy, mature gentleman, you’ll want to concentrate on the uptown ones, such as the bar at the aptly named Mark Hotel, on 77th Street and Madison Avenue. And of course there are circuit standbys like the Peninsula rooftop, where, on a recent balmy weeknight, Diane Passage is sitting at a table holding court with, as she had indicated by text message, several “v. handsome men.” She’s relaying a story about another evening at another perennial, the Waldorf-Astoria, where a guy paid her $100 to kick him in the balls: “He was into humiliation or whatever.” She giggles. Passage is a petite, smoky-eyed Kardashian brunette, and when she laughs, her grapefruit-tree physique bounces merrily. “It was so weird.”“What’d you do?” asks one of the men, a ruddy real-estate developer we’ll call Barry.

“I kicked him in the nuts!” she says, like duh. She’d been sitting at the bar with a friend who “kind of looks like a hooker,” so it wasn’t surprising when the well-dressed man who’d bought their drinks made a business proposal.

“We went into this little area and he was like, ‘First, go into the restroom and make me wait,’ ” she says. “So I went into the bathroom for like fifteen minutes and I was texting all my friends and then I came out and I kicked him in the nuts and he was like”—she drops her voice down to a meek whisper—“ ‘Thank you.’ ”

Passage giggles again, and the ensuing undulations manage to pull Barry’s attention back from the blonde who’d just passed by.

“Shots!” he says decisively. His friend, let’s call him Paul, a tall, paunchy private-equity manager who was quiet much of the evening but has become considerably more animated after a trip to the bathroom, pounds the table in agreement. When the shots of Patrón arrive, Passage sips hers slowly; when Barry protests, she just smiles. The men, meanwhile, are wasted.

“Am I a good boy or a bad boy?” Paul asks.

“Aw, you’re a good boy, Paul.” Passage laughs. She laughs a lot.

Passage is one of those people that it feels like New York invented, though they thrive wherever male egos and dumb money coexist. She’s the kind of woman who is able, through physical charms, nifty tricks of persuasion, and sheer gall, to inspire men to pay for … well, everything. She’s like Holly Golightly, if Holly Golightly had to kick a guy in the nuts when she went to the powder room. Which, in postrecession New York, she might have.

But not so long ago, Passage wouldn’t have entertained the idea of sexually humiliating a man for a mere $100. She wouldn’t have been at this bar, with these guys, taking a small puff of Barry’s spit-covered Habana cigar because he’d thrust it in her face and said “Suck it.” Until quite recently, Passage was the happy protagonist of a modern-day fairy tale: A single mother who, four years ago, was plucked off the dance floor at Scores by a financier who promised to change her life. And change it he did.

At first glance, Kenneth Starr was no one’s idea of Prince Charming. He was in his sixties, he was married. But he was a money manager (not to be confused with the Whitewater investigator) and clearly successful, if the list of phone numbers of clients he scrolled through on his cell phone to impress the strippers was any indication: Al Pacino, Barbara Walters, Bunny Mellon, Candice Bergen, Caroline Kennedy, Diane Sawyer, Harvey Weinstein, Nora Ephron, Scott Rudin, Warren Beatty, Carly Simon—it went on and on, a Who’s Who of famously wealthy people in America in the 21st century. He had plenty of cash to throw around, especially, it turned out, when it came to Passage. After his whirlwind divorce and their equally whirlwind Vegas wedding, Passage moved with her son from a small walk-up to a $7 million condo on the Upper East Side in a building so sure of its fabulousness that it was called “Lux74.” In a year, she went from rubbing customers’ legs at bachelor parties to rubbing shoulders with celebrities at the Vanity Fair Oscar party.

Last year, on their third anniversary, the couple toasted their good fortune in front of a small group of friends and clients at Cipriani. Passage, holding court in that season’s Gucci, was content. She was married to a wealthy man. There was no prenup. She was never going to have to struggle again. She was Cindefuckingrella.

Last year, on their third anniversary, the couple toasted their good fortune in front of a small group of friends and clients at Cipriani. Passage, holding court in that season’s Gucci, was content. She was married to a wealthy man. There was no prenup. She was never going to have to struggle again. She was Cindefuckingrella.

A couple of days later, federal agents showed up at their apartment and arrested Starr. The SEC and the U.S. Attorney’s office had charged him with conducting a massive Ponzi scheme. “It’s a mistake,” he told her, after the cops dragged him out of the bedroom closet. But it wasn’t. Documents showed Starr had embezzled $33 million from clients. Passage was named as a co-defendant, and her bank account was frozen. It was as if her fairy godmother had suddenly reappeared and said, “Sorry, wrong girl.”

In the days after Starr’s arrest, the tabloid reporters camped outside the Lux heard an agonized wail coming from inside. “I’ve done nothing,” said the female voice. “Now I have nothing.”

This March, Passage, now 35, sat in a courtroom and listened as a judge with glasses and Janet Reno hair pronounced her husband guilty. “He seemed to have lost his moral compass,” the judge said, “partly as a result of infatuation with his young fourth wife.” Passage, sitting in the front row, was startled. Starr had said she was his third wife. Maybe she had misheard?

No, she hadn’t. The Post later reported the remark, adding the observation that Passage’s “cleavage was so generous that she used it to tuck in her sunglasses.”

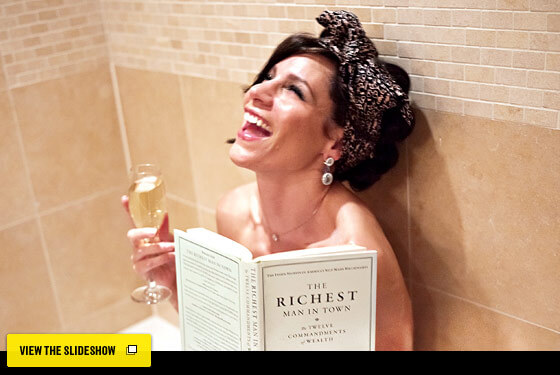

Great—not only was she broke, she was being publicly slut-shamed. Not without a sense of humor, Passage added “moral-compass disabler” to her Twitter bio. If you’ve got it, you might as well use it. Which is what brings her to the Peninsula on this lovely Tuesday night.

It doesn’t take that many tequilas before Barry, a friend Passage made post-Ponzi, starts to get emotional. “She’s got a good heart,” he says, laying a hairy hand on top of her left breast. “She’s a nice person.” He goes on, with the sincere clarity only the extremely drunk exhibit. “She is brilliant with men. She knows what she’s doing. She’s trying to make whatever she can with what she’s got. She’s going to get out of all this bullshit. And,” he adds with a snort of laughter, “she loves it in the—”

Passage swats him playfully. “And I love kicking guys in the balls and humiliating them,” she says. Yes, and you can imagine there are times that might feel pretty damn good.

One of the things Passage dreamed about doing, once Starr’s seemingly limitless money opened up a world of possibilities to her, was writing a book. She still wants to, although, given the change in circumstances, she’s rethinking the idea. “Something like The Game, for women,” she mused recently. “Or something called How to Get What You Want From Any Man.” She’s also contemplating a memoir.

Her story might begin with that old cliché, a girl arriving in New York and looking up at the dazzling lights of Times Square. It was 1994, and though she’d planned her outfit carefully—a distressed floral-print dress in the style of Courtney Love, combat boots, and a flannel shirt—she was less sure what she wanted to do when she arrived. As a kid, she’d dreamed of becoming a pop star or a veterinarian, but she couldn’t carry a tune and was allergic to hairy animals. By the time she was 18, all she really knew was that she needed to get the hell out of Detroit. She’d figure something out. “I always had a good head for business,” she says. “And I hustle like crazy.”

One of the first men she met in New York hooked her up with a job selling voice-mail accounts, a place to live, and a musician boyfriend, who a few years later became the father of her son, Jordan. They tried to make a go of being a family, moving to Brooklyn not long after Passage graduated with a marketing degree from F.I.T., but she was bored and restless, and she and her son soon decamped to an apartment in Times Square. Ten years, several cities, and a brief marriage later, Passage was again supporting her son on her own in New York, selling classified ads for a small agency called Bayard. She was good at sales—she had charm, a sultry walk, “a little tilt in the hip,” says one former co-worker—and had an ability to soothe even the most difficult clients. But money was tight.

“If I was you, I know what I’d do,” said a male colleague one day in 2004, when she confided her problems. He eyed her curvy figure. “I’d go straight to a strip club.”

Some women might have gone straight to human resources. But Passage is a person who considers all offers. “Really?” she said. “I’ve never even been to a strip club.”

She decided to go on a research trip. Sitting alone at the bar at Scores, she was fascinated by the women working the room in G-strings and heels. “They hustled like no one’s business,” she explains. “They were their own little CEOs, basically.” She auditioned that day and started working that night. Her first dance was to Madonna’s “Material Girl.”

It soon became clear that her nine-to-five was no longer worth getting out of bed for. “During the day, I’d watch these salespeople talk and jump through hoops,” she says. “And at night I’d go to work and watch these girls making $400 an hour to get people to go to rooms where nothing happens.” She widens her eyes. “Like, these girls are better than people who went to school and got master’s degrees and bachelor’s degrees.”

Scores was a different kind of education. On the floor, Passage learned how to read customers, “to figure out who was real” and what they were willing to give. “Even if they’re not wealthy, sometimes it’s a priority for them to spend $2,000 a week,” she explains. In the dressing room, she learned little tricks for getting something extra, to help pay your rent, perhaps, or your student loans, or buy you the new Gucci shoes. It all really boiled down to one thing: “There’s a great line inThe Other Boleyn Girl,” she says, in which Anne Boleyn’s mother gives her advice: “You have to allow the men to believe they are in charge,” Passage intones dramatically. “ That is the art of being a woman. ”

This advice didn’t work out for Anne Boleyn, but it did for Passage, who started using Scores tactics outside the club, too. “Let’s go on a hustle,” she and her friends would say before heading out to a bar. One of her friends from that time got so good she installed a credit-card swiper on her iPhone in order to take immediate donations. “She doesn’t even need to get them wasted,” Passage says admiringly.

But what all the girls talked about, while they were coating themselves in body spray and covering up their tattoos, was their “arrangements”—the longer-term sugar daddies. And eventually, between the dressing-room talk, the abject behavior of men on the Scores floor, and her own disappointments, Passage started to rethink her approach to dating. “I used to believe in love and romance,” she says. “But I felt like in a lot of cases I was contributing too much to my relationships. It was time,” she says, laughing, “to let someone else contribute.”

It took a year before the perfect prospect fell into her lap. Or, more accurately, she fell into his.

Ken Starr was in the market for a somewhat unusual arrangement, as evidenced by the fact that he came to Scores with his wife, Marisa. It was a busy night at the club: The billionaire entrepreneur Mark Cuban was there, and the band Korn. But the Starrs were on a mission, and they had cash to burn. They herded several girls into the Champagne room and, at the end of the night, offered Passage and another dancer $1,000 each to come to dinner at their Park Avenue penthouse. It was a little weird, the women thought, but hey, $1,000 was a night’s work, and the Starrs promised they wouldn’t even have to take off their clothes.

After some nervous chitchat over Chinese, Ken spoke. “I bet you’re wondering why we invited you here.” The couple had an open marriage, he told them, and Marisa was looking for someone or someones to occupy her husband while she spent time with her boyfriend. They’d pay $1,000 a date. The women shrugged, and agreed to go out a few more times as a foursome, though Passage’s friend never made it past the second date, after she arrived at The Four Seasons in jeans. Later, Passage says, Marisa cornered her. “Don’t try to steal him from me,” she hissed. But after that, it was just her and Ken.

The Starrs bragged a lot about their properties and their relationships with celebrities, but even with the skills she’d honed at Scores, Passage couldn’t get a read on how big a fish she’d caught. She asked a public-relations guy at the club how to find out if Ken Starr was for real.

“Ask him to take you to Per Se on short notice,” he told her.

When Starr called to set up a follow-up date, she was ready. “There’s this restaurant I really want to go to?” she began sweetly. Starr secured a reservation for that week.

It took a few dates for Starr to open up, but after a while Passage came to realize that he was a hustler much like her. He’d grown up in the South Bronx and entered college at 15, after which he worked his way into the city with a job at a big accounting firm. He told her an apocryphal story of how he landed his first high-net-worth client, Paul Mellon, while he was still a no-name paper-pusher. “Who’s your accountant?” the heir to one of the country’s largest banking fortunes, annoyed by his own bookkeeper, had supposedly said to his florist, who stutteringly gave him Starr’s name. The association with the Mellons had changed his life, Starr told her. Once he had them, getting the other big names was relatively easy.

Not that Starr didn’t make an effort. He was a schmoozer and made sure his calendar was packed with all the right events—charity dinners, movie premieres, restaurant openings—where wealthy and powerful people would be. Starr started bringing Passage with him to everything from movie premieres to a talk with Henry Kissinger at the Council on Foreign Relations. “I don’t know if I have the right clothes for that,” Passage suggested. “Maybe we could go shopping?”

She barely needed to ask. Starr delighted in making her over. They went shopping for dresses at Escada and Bloomingdale’s. Passage told him she felt like Julia Roberts in Pretty Woman, and he said she reminded him more of Holly Golightly; when she said she didn’t know who that was, he rented the DVD ofBreakfast at Tiffany’s. Even so. “I look at old pictures of us from some of these events, and I look like he just picked me up from Scores and put me in a suit,” Passage now says. “I had the lashes and probably body glitter. It was a bold move on his part to have brought me to some of those things.” In retrospect, she suspects there was a part of Starr that wanted to show the clients who treated him like a lackey that he’d made it to their level—that, like them, he could do whatever, with whomever. He loved, for instance, telling the story of how Passage fell asleep when Kissinger was talking, joking that he was sleeping too, because Kissinger was so boring.

“The majority of women on Park Avenue are probably up to worse stuff than I ever was.”

But Starr was fun. He was smart and funny and “knew everything about everything. The more time we spent together, the more I really started to enjoy his company.” They became sort of friends-with-benefits, although at first the benefits were weighted toward Passage, who refused to sleep with him. She wasn’t a prostitute, she’d say. This went on for approximately a year, until the summer of 2006, when Starr showed up at the Hamptons house he’d rented for her and said he’d fallen in love with her and wanted to leave his wife. “After that, we decided to be in a relationship,” she says.

Starr proposed on Valentine’s Day 2007, proffering a $32,000 diamond ring. They planned a June wedding in Las Vegas at the Wynn hotel, and it was just close friends and family: Passage’s son, Jordan, served as best man, along with the basketball player Julius Erving. The maid of honor was a girl from Scores called Lydia.

Back home, Passage’s friends at Scores were shocked: “You’re not supposed tomarry them,” one of them told her, aghast.

“I was pretty surprised, to be honest,” says one former dancer, whom we’ll call by her former Scores name, Heather, since she’s now married to a doctor and living in a small Christian town in the Midwest. At the same time she was dating Starr, Passage was dating other wealthy, eligible men, including a record producer and a celebrity chef. “But I guess Ken was kind of her knight in shining armor that was going to give her a better life,” Heather says. “I mean, you can’t dance forever.”

A week later, the new Mr. and Mrs. Starr hosted 100 people at a wedding reception at the Central Park Zoo. Passage wore an Alexander McQueen dress (just like Kate Middleton, she later pointed out). “It was stunning,” she says. “Stun-ning.” The day had only one flaw: When Planet Hollywood founder Keith Barish stood up to give a toast, the D.J. accidentally hit the PLAY button.

The song that came on was Kanye West’s “Gold Digger.”

After the wedding, Starr amped up the couple’s already vigorous social schedule. “It was really important to him to be visible,” says Passage. And with her he was. Who could miss the brunette bombshell with Audrey Hepburn cheekbones and breasts augmented so that each was roughly the size of a human head, accompanied by a beetle-browed accountant old enough to be her father?

The attention was intoxicating to Starr. “She was his little doll, his pride and joy that he loved to show off,” says Joan Jedell, the publisher of Hampton Sheetmagazine, which, at Starr’s urging, put Passage on the cover in 2008. (“WOW! Who is the stunning beauty on the cover of Joan Jedell’s Hampton Sheetmagazine?” Liz Smith gushed in the Post. “Joan tells me Diane is married to financial wiz Ken Starr.”)

Passage wanted to do something to help single mothers, and Starr helped her set up a nonprofit called S.P.I.N. (Single Parents in Need) and a pole-dancing competition, Pole Superstars, to help fund it. But as eager as he was to please her, and enamored as he was of her God-given talents—one year, at the annual Allen & Co. retreat in Sun Valley, he played a video of Passage’s pole-dancing on his iPhone for a group of moguls—Starr was also aware of the optics. “It was important to him that I have some sort of career title when he introduced me to clients,” says Passage. He encouraged her to pursue a career in the entertainment industry, introducing her to producers and urging her to develop movie projects. She loved music, so he goaded investors into buying an interest in a record company so that she could work in A&R. He also pushed Passage to shed her friends from Scores and pal around with socialites instead. This was easier said than done. “Needless to say, society was not that receptive to Ken’s young wife, the stripper from Scores,” says Jedell.

“I got a reputation for being a gold digger,” Passage says. “But I would say that the majority of women on Park Avenue are probably up to worse stuff than I ever was.” Occasionally at parties, Starr, with his intimate knowledge of the financial lives of the rich and famous, would fill her in on the backstories of the people in attendance. “There are a lot of women married to powerful men who come from colorful backgrounds,” she says. And there were plenty of hustlers. Like the Upper East Side doyenne who forced her husband to sign over property by threatening to reveal that he was gay. Or the well-known woman whose relationships with exclusively high-net-worth individuals came with an expiration date—if they don’t propose in the allotted time, she moves on. That, to Passage, was especially redolent of Scores, where dancers will call it quits on a customer if they don’t spend enough money after two or three songs.

At one event, Starr pointed out a billionaire and the new wife he’d met online. She was a single mother and had been living in a trailer park when they met, Starr said, and they’d fallen madly in love.

“Please,” Passage said, eyeing the husband, who was much older and had to be a full foot shorter than his wife. “She’s nothing but a contract whore.”

“He always just saw the romance,” she says now, “but that’s not how I saw it. I saw 80-year-old men with 40-year-old wives. I saw a lap dance, a blow job, a Mercedes.”

Starr pouted the rest of the night—her comment had perhaps hit a little too close to home. Passage says she didn’t marry him for purely mercenary reasons, and by all accounts, he was besotted with her. But “there was always an element of it that still felt like an arrangement,” she says. “I was his show pony.” And she was expected to perform. Ken’s social mania meant the couple was out nearly every night, and it took a toll on her relationship with her son, who was coming home from school around the time his mother was getting her hair and makeup done. For what? Sometimes she didn’t even know. “Some of those black-tie events were so fucking boring. We went to one at Blackstone? Their holiday party? I was like,I can’t believe I spent so much time getting ready for this.”

But the pros outweighed the cons. “Ken never said no to me,” Passage says. She got whatever she wanted: diamonds—at least a quarter-million dollars’ worth, according to the U.S. Attorney’s office—designer clothes, even a new pair of boobs. They went to Egypt to hike Mount Sinai, to Rome to see the Sistine Chapel, to Hawaii to swim with sharks. In April 2010, Starr paid $7.5 million for Passage’s dream home, a five-bedroom triplex on 74th Street with a pool and a home theater. A few weeks later, they had friends over to celebrate in their 1,500-square-foot garden flanked by towering bamboo fronds. Passage worked the crowd in a blue Gucci dress from that season. She was the perfect Upper East Side hostess, albeit with a tattoo snaking around her arm. It was the first and last party in their home together.

These days, the bamboo is jaundiced and bent. The pool’s heater is turned off, and Passage has forgotten how to work the projectors in the plush theater where she holed up for months after Starr’s fraud was revealed, mindlessly watching episodes of Ace of Cakes. “Welcome to the Titanic,” she said when I visited a couple months ago, warning me to avoid a leak in the ceiling of the mansion that she and her son were essentially squatting in, waiting to see which of their belongings, if any, they would be allowed to take with them. (“Think the U.S. Attorney wants to repo them?” she joked of her breasts.)

Jordan was home, getting ready for school, when federal agents came knocking on the door of apartment 1C with a warrant for his stepfather’s arrest. “What’s going on?” he asked his mother, tears streaming down his face, after they marched Starr out the door. “I don’t know,” she told him. It wasn’t until they turned on the news that they heard what had happened: How Uma Thurman had stormed into Starr’s office, irate about a missing million dollars, and how a wave of clients had followed, demanding redemptions that Starr, it turned out, had been incapable of giving, since, according to the complaint, he had misappropriated millions “for his own personal use, including to purchase himself a new, multimillion-dollar residence.”

The following weeks were a blur. Starr swore to her that he had done nothing wrong, even as the facts increasingly contradicted him. Still, Passage tried to believe him. Certainly, his version of events was preferable. Then she found out that he’d lied to her about the timing of his divorce from Marisa (it had come through only two weeks before their wedding), and she was apoplectic when she learned from Vanity Fair the details of their generous settlement. Adding insult to injury, she found out she wasn’t even his third wife but his fourth. “The fact that he had this whole other wife,” she says, shaking her head. “I was so insulted. I mean, I’d told him everything.” Worse, Starr lied to her when she confronted him about it. “He was like, ‘It was an arrangement’; I was like, ‘Yeah, it was. It was a marriage, you idiot.’ I mean, don’t hustle a hustler.”

Because she was named as a co-defendant in the SEC case, the agency froze her funds, including, Passage says, her savings from Scores. Still, she hasn’t taken a job, mostly because she’s afraid the SEC would seize her wages and use them to pay off the Carly Simons and Bunny Mellons of the world, a distribution of assets she sees as grossly unfair. “I mean, really?” she says. “My husband got in trouble, so I’ve got to give restitution money too?” These days, she’s surviving on the “generosity of family and friends”—some of whom are former Starr clients—and her own “creativity.” “Jordan’s a hustler too,” she says proudly of her son, now 13. “He’ll be like, ‘Mom, can I get you coffee?’ And of course I don’t see the change.”

All summer long and into the fall, she stayed furious with Starr. She wouldn’t answer his calls from prison. So he wrote long e-mails in which he pledged his love and promised he would make it all up to her, as soon as he cleared up what he still implied was a misunderstanding. “I thought I was doing all I could to continue to be successful but I will do more,” he wrote in one e-mail. “You will have more than you will ever need and I want you to flaunt it,” he promised in another, after his friends and family refused to post his bail. “Mostly because I love you so much,” he added, “but also because I want them to choke on it.”

By the New Year, he finally said what she wanted to hear. “He told me what he did, and really expressed a lot of remorse,” Passage explains. “And I finally felt his ego sort of go away. It was his ego that got him into this, you know, in the first place.” Looking at her husband, humbled in his blue prison garb, “I kind of gained a whole new level of respect for him.” And for the first time, Passage felt like she could be herself, that they were equals. “Before he was arrested, our relationship was sort of shallow,” she says. “This winter, I felt like we were able to just really connect. And our relationship became more real.”

For the next few months, they talked at least five times a day and saw each other once a week. “More roses from Ken just arrived!!” she tweeted in February. “Even from behind bars he continues to make other husbands look like a$$holes … Lol!”

But by the spring, reality was setting in. “The other day I was thinking, for a quarter of our marriage, he’s been incarcerated,” she told me in May. “That’s kind of significant.” And she’d spent the last few visits yelling at him. “Sometimes I get really angry at the situation,” she said. “Our relationship is not exactly fun anymore.” In June, she wished him a happy anniversary by text, and when she told him she was seeing other people, he understood. “My hope for her is simple,” Starr writes in an e-mail from prison. “That she has the life she wants and dreams of—she deserves it.”

“Am I a good boy or a bad boy?” Paul asks again, as the car pulls up to the Mark Hotel. Frédéric Fekkai, sitting at a table in the bar area, breaks his conversation to watch as Passage settles into a table, pulling her skirt daintily over the tops of her thighs. While Paul busies himself with hugging the restaurant’s employees, Barry, who has by now turned a shade of plum, orders another round of drinks.

It’s late July and Passage has recently been to see a divorce attorney, though she says she hasn’t yet told Ken. “Not yet,” she says. “I promised him that I would never abandon him. Because I love him. But I can’t stay married to him. Ah, that tickles!”

Paul is dangling a napkin across her head. “Am I a good boy or a bad boy?”

Her lawyers are working to get her funds unfrozen by the SEC, and she’s starting to think seriously about the next chapter of her life. She’s been consulting on opening a nightclub in the Flatiron district “that caters to an older audience,” with Tommy Tardie, of La Pomme, and she mulled a few reality-TV projects, including a show about Scores dancers, before deciding the genre is “tacky.” In the meantime, she still has to make a living. Around midnight, Barry pays the check in cash and immediately collects on his investment, pulling Passage to him. As they make out at the table, Paul grows morose. “Do I look old?” he asks. “I used to be a quarterback at Notre Dame!” He buries his head in his hands.

As it turns out, Passage didn’t have to tell Starr that she was filing for divorce. He read about it in “Page Six.” A few days after the night out with Barry and Paul, she’d been at the nail salon, flipping through Newsweek, when she got the call from the Post confirming it. Inside the magazine was a picture of herself and Starr, alongside an article about the trials and tribulations of Bunny Mellon. “I had hair extensions, I’m wearing like diamond earrings and a cocktail dress,” she says. “It doesn’t even seem like me.”

And it wasn’t anymore. Last week, Passage and her son finally moved out of the Lux. They’ve ended back where she started, in Times Square. “I think I fit in better here,” she says, calling from their tiny apartment overlooking the glittery, dirty center of Manhattan, where people from everywhere arrive each day to live out stories whose endings they can’t yet imagine.