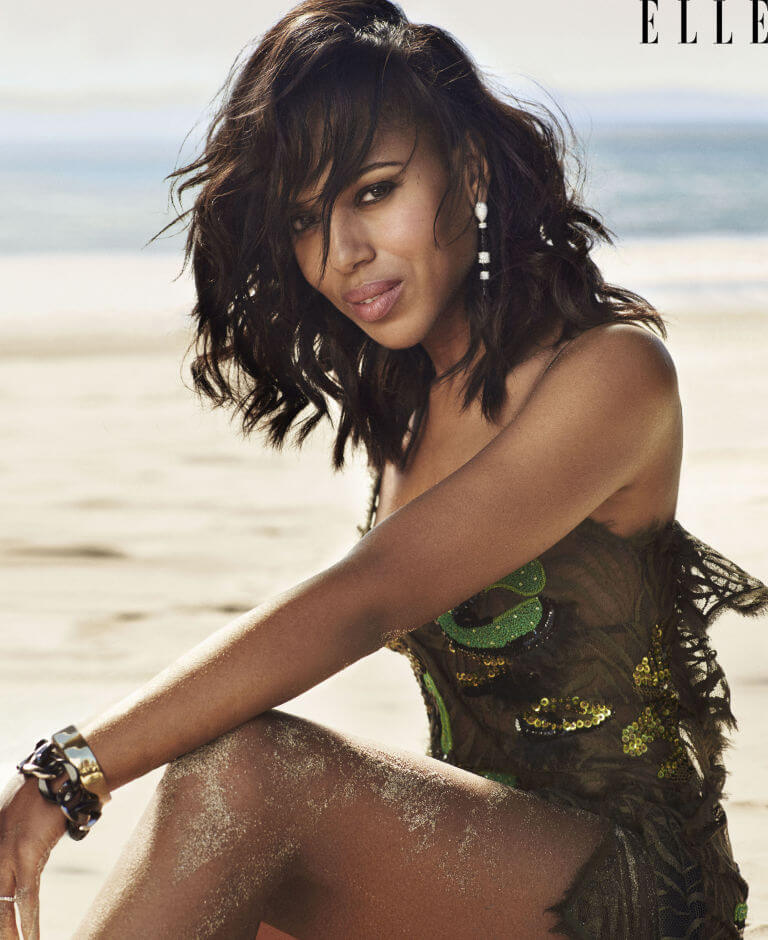

Our April cover star–a self-described “person who has always been politically active and passionate about people’s rights”–opens up about her most political project to date.

In 1991, the year Anita Hill, a 35-year-old law professor from the University of Oklahoma, appeared at the confirmation hearing of Supreme Court nominee Clarence Thomas, Kerry Washington was just 14 years old. But like everyone else, she was transfixed by the two days that followed, in which Hill calmly recounted in front of the Senate Judiciary Committee the sexual harassment she claimed to have experienced while working for Thomas a decade prior at the Equal Opportunity Commission. “It was a big deal in our house,” recalls Washington, who watched the televised hearings with her parents in their apartment in the Bronx, New York.

It wasn’t just the salacious nature of the allegations or how weird and incongruous the words “Long Dong Silver” sounded coming from Hill, a demure Midwesterner in a turquoise dress (not to mention reverberating around the hallowed halls of the Hart Senate Office Building). The sight of a black woman testifying alone before an all-white, all-male Senate Judiciary Committee, and the vociferous denials of Thomas, the conservative, second-ever black nominee to the Supreme Court, who claimed Hill’s testimony had been engineered by political adversaries as part of a “high-tech lynching,” laid bare some discomfiting truths about race and gender in American politics and life in general.

“I remember my parents and their friends having a very deep reaction to the lynching statement and thinking, This is the public destruction of an African American man,” says Washington, sitting at a corner table at the Sunset Tower Hotel in Los Angeles. “There was something really devastating to the black community to be watching that happen, and watching that happen at the hands of a black woman. At the same time, I remember my mother and her friends feeling so aligned and empathetic and in defense of her.”

Twenty-five years later, everyone remembers how it all played out: Thomas got his seat on the Supreme Court, although he will be forever associated with the imagery of pubic hair on a Coke can and the distasteful nature of the proceedings that left the country with a moral hangover, which led to federal protections against sexual harassment and an increase in the number of female political candidates.

Since that time, Kerry Washington has transformed from a scrunchie-wearing, a capella–singing kid into a glamorous Hollywood star, one whose power and talent affords her the ability to make a movie about the events she witnessed as a teenager. “This moment was so important because it created a language around women being able to protect themselves,” says Washington, who is executive producer on this month’s HBO movie Confirmation, a dramatic retelling of the proceedings in which she also stars as Hill. “The behavior that Anita Hill described was going on in a lot of offices throughout the country, and most people didn’t think they were doing anything wrong. But this created awareness around that and around the need for women’s voices to be heard in our public spaces, both testifying before Congress and sitting on the committee. It really was such a huge cultural shift.”

Looking at Washington, huge brown eyes unblinking as she advocates for her passion project across the table, it’s hard not to also see Olivia Pope, the DC fixer she plays on ABC’s hit showScandal. And indeed, Washington admits, after five seasons the two are pretty inseparable. “There’s a lot of me in her,” she says, with an enigmatic smile. “A lot.” Although it’s hard to imagine Olivia Pope dressed so casually, in jeans and a leather jacket, she’d probably also pair them with the Tod’s loafers that Washington has on, and the eye shadow so perfectly applied that our hostess gushed over “how natural” it looks. In real life, as on Scandal, which credibly featured a plot line casting her as a modern Helen of Troy—”the face that launched a thousand ships”—Washington’s radiance reduces the rest of us mortals to sputtering and staring.

“Do you have any warm vegetable sides?” she asks.

“We can make whatever you like,” the waiter, a shaggy L.A. bro, offers magnanimously.

“What about asparagus?” she asks, turning her face quizzically toward his.

“I, uh,” he gulps, his cool puddling to the floor as he takes in her expression—the brow beginning to furrow in disappointment, the lip beginning to quiver in the same precipitous way that Olivia Pope’s does whenever someone close to her is revealed, yet again, to have a secret identity. “I, uh—I’ll check on that,” he says. “I’ll do that now, okay?”

Washington smiles as he slowly backs away, then flees. “That was adorable,” she says, casting her eyes modestly toward the napkin in her lap, although this is clearly the sort of thing that happens to her all the time now that she is superfamous. Washington was a successful actress before she became Olivia Pope, playing supporting roles in a slew of well-known movies. “But I was, for most of my career, able to be invisible,” she says. “For some reason, people never connected that the girl from Ray was the same girl from The Last King of Scotland.” That changed when Scandal happened. Part of it is just the beast of television. “Taraji and Viola and I,” she says—referring to Taraji P. Henson of Empire and Viola Davis of How to Get Away With Murder, both also film stars who made the switch to the small screen—”we have these conversations: Television changed the game. Coming into people’s houses on a weekly basis is just a different kind of relationship to the public.”

It doesn’t take long, when you are talking to Kerry Washington, to realize the main character trait she shares with Olivia Pope is that underneath the cool, collected demeanor lies a well of sensitivity. Although after four years she has become accustomed to handling the attention that comes her way with enormous grace, it obviously still makes her uncomfortable. “It’s so interesting to me that people say about actors, ‘Well, this is what you asked for,'” she says, as two women by the pool crane their necks to get a glimpse of her. “No. What I asked for was to tell stories and do work that I love, and this was the byproduct of that journey.”

As a result, Washington has gotten, as she puts it, “a lot more guarded” than in her early years, when she talked freely about her personal life. She and her husband, former Oakland Raiders player Nnamdi Asomugha—whom she married in a secret ceremony in 2013 and has a baby girl with, the soon-to-be-two Isabelle—have made a vow not to speak to the press about each other. Which apparently extends even to her being able to confirm where they’d met (reportedly, during her run on Broadway in Race). “He’s not in the room, so I can’t really say,” she says, squirming. “I guess that’s what partnership looks like for me in that area now.”

I’m just going to say Tinder, I tell her. “Yes,” she says, laughing. “I swiped him. He was my first swipe.”

There are some positive aspects to the notoriety, as Olivia Pope would surely point out, the main one being power. Washington has used her elevated profile to support causes she believes in. A staunch Democrat, she stumped for Obama and spoke at the 2012 Democratic National Convention. She’s been highly active in two charities that help victims of domestic violence, V-Day and the Allstate Foundation Purple Purse. And she has gone on record to praise Scandal‘s forays into hot-button topics like police shootings and abortion rights. “I am a person who has always been politically active and passionate about people’s rights,” she tells me. “I marched against the [2004] Republican Convention. And as my career has expanded, it’s been important for me to not stifle that voice. Because you want to be popular, you want people to hire you, and I have to make sure I don’t do it less because I’m an actor.”

With Confirmation, Washington used her muscle as a top star to bring attention to a story that was left for dead but is still, in many ways, very much alive. “It’s still so relevant in terms of, Do we believe people when they say they have been victims? How do we respond as a society?” she says. “It’s important that we live in a world where, if someone is wronged, they have the room to tell the truth about it. Like if someone is treated as less than a human being for the gratification of a more powerful person—I want to live in a world where that is not okay, where that person has ways to defend and protect herself.”

For Washington, the film is a “very natural fit,” says Jeffrey Wright, the actor Washington asked to play Charles Ogletree, the Harvard lawyer who represented Hill. “I don’t think there are too many other actors who could legitimately pull it together. Kerry occupies a unique place that is legitimately political and well-measured and reasonable. She’s that rare thing for an actor,” he says, laughing. “She’s thoughtful.”

A lot of celebrities talk the talk, but it’s true that Kerry Washington has always been thoughtful in this way. “From the beginning of my career, I have always tried to make really conscious decisions about the kinds of work I do,” she says, “knowing that what we are a part of can really construct and contribute to the cultural conversation.” Starting with her first-ever acting job: At 14, the same year as the events in Confirmation, she joined an acting troupe that performed skits to educate kids at area high schools about safe sex. “I was the youngest person in the company,” she recalls. “So I was only allowed to do skits about whether or not to lose my virginity.” At that point, she was already a student at Spence, the tony Upper East Side private school that counts Gwyneth Paltrow among its famous alums.

Washington attended on scholarship, commuting from the middle-income housing development in the Bronx where her family lived. “For a lot of classmates, I knew the only other black women they’d known had been their domestic help,” Washington has said in the past. She’s now more circumspect. “It was definitely a world I did not know,” she says, blowing on her hot water with lemon. “I basically had to learn how to be culturally bilingual, to be bicultural, because it was important for me to remain close to my family in the Bronx. And learning to traverse those two worlds was challenging at times.” Though it ultimately ended up being a useful skill. “Now there aren’t too many places I feel uncomfortable,” she says. “I think you also start to kind of recognize the cultural cues for identity. Like, here in this world, they listen to this kind of music, they dance this way and wear this kind of shoes. I probably use a lot of those experiences in my acting.”

Not that she got to use them right away. While Paltrow, a senior to Washington’s freshman, sailed smoothly (no doubt with some help from her Hollywood royalty parents, director Bruce Paltrow and actress Blythe Danner) after graduation into dating Brad Pitt, winning the Oscar for Shakespeare in Love (for which, of course, the work speaks for itself), and Bringing Back the Color Pink, Washington’s path was a little rockier. After graduating from George Washington University in DC, she moved back to New York and worked multiple jobs to support herself on the audition circuit, like teaching yoga and hostessing at a vegan restaurant. Even after she landed the role of Chenille in 2001’s Save the Last Dance, the cool teen mom who teaches new-to-the-hood Julia Stiles how to fit in by, among other things, magically repurposing her sweater set into a bandanna, Washington had to go back to her day job as a substitute teacher in Harlem. It wasn’t until she was cast in Scandal that she was finally able to pay off her student loans.

The struggle calls to mind something Rowan Pope, Olivia Pope’s murderous sociopath of a father, told her in season three: “You have to be twice as good as them to get half of what they have.” “Every African American I know says that’s what every black parent says,” Washington says. “I definitely did bring a certain kind of work ethic because of where I come from. But it’s tricky in acting. Saying you want to be a successful actor is like saying that you want to win the lottery. I also know people who work twice as hard as I do and don’t have half of what I have.”

The waiter returns, triumphantly bearing the asparagus and a flushed look that suggests he plucked it off the nearby hills himself, and Washington rewards him with a movie-star smile.

When she was first presented with Scandal, she wasn’t sure about it. At that point, she was well on her way to a résumé full of worthy projects, indie dramas like Our Song and literary adaptations like The Human Stain and lovably provocative movies like Spike Lee’s She Hate Me.

She thought the Scandal script was “brilliant,” but Shonda Rhimes made her nervous. “I remember getting off the elevator at her office and seeing this sign that said ‘ShondaLand’ and being like, Are you kidding me?” Washington says. “And then, three minutes into our meeting, I was madly in love with her.” Washington found that Rhimes embodied a kind of quiet activism she admired. “She’s not in the world saying ‘I’m a powerful black woman in Hollywood,’ ” Washington says. “She just is one, and that’s the message she carries just by living her life fully.”

Now Washington considers her boss a friend and mentor. “She’s been such an amazing resource, as a mom, and as a working mom,” she says. “I am on one show and I have one kid, and she has three shows and three kids.” Right now, she says, departing from her no-family-talk rule, her husband is at home listening to the audio version of Rhimes’s book, the first-person self-help journey Year of Yes. “We bought it for a bunch of people for Christmas because I feel like it’s a little bit of required reading.”

There are “threads of Shonda” in Olivia Pope, a character Washington has leaned on, especially when she learned she was pregnant during Scandal’s third season. “Even though Olivia Pope has obviously made the decision that she is not a mom,” Washington says, in reference to the 2015 midseason finale, in which—spoiler—Pope gets an abortion, “playing her made me feel like I could be a mom. Because she knows there’s always another way—there’s always a way to fix it, there’s always a way to solve it, to win. And I feel like playing her made me feel like, All right, I can do it. I will figure out how to juggle it all.”

But it was the real-life Rhimes who provided more tangible comfort. “Please note,” Washington says, raising her fork to emphasize her point, “that when I told Shonda Rhimes I was pregnant, she literally jumped up and down with joy. That is not the reaction, I guarantee you, that a lot of the executives at ABC had. They were like, What does that mean for the show? She just was happy for me. She was like, ‘We’ll figure it out.’ That’s rare in this business, in any business, for a woman to have that reaction from her boss.”

It follows that time spent in this atmosphere would encourage Washington to pursue her own ambitions. “At this point in my career, it felt important for me to be creating work for myself, and not, like, sitting at home and waiting to be invited to a party,” she says about her decision to begin seeking out projects to produce after she was back from maternity leave. “I’ve been so lucky, and I want to make sure the level of work continues to be as good. So I thought, Maybe I should take a seat at the table and be part of the team that makes things happen, instead of putting my artistic destiny in other people’s hands.”

That’s when Washington’s agents told her about Anita: Speaking Truth to Power, a 2013 documentary account of the hearings by acclaimed filmmaker Freida Lee Mock that—unusually—Hill had participated in. “I’d been asked to do documentaries several times,” Hill told me over the phone from her office at Brandeis University, where she now teaches law. But previously, the idea had never appealed to her. The notoriety from the hearings turned her life upside down, and although she’d since gracefully accepted her role as the godmother of sexual harassment laws and an advocate for women’s rights, she was also enjoying the relative privacy bestowed by the passage of time. Many of her students hadn’t even been born in 1991 and didn’t know the story, and she didn’t particularly relish the idea of going over it all yet again. Lately, though, issues and concerns over victims’ rights and sexual consent were bubbling up in a way that Hill found disturbing. “The kinds of questions that were getting asked when it came to rape or sexual violence were ‘Why didn’t they come forward?’ ” she says. “And finally it occurred to me: This [film] was an idea I could get behind and work with. Because when those things keep coming up, it’s time to revisit and inform people about what happened before and how we can respond. How do you come forward and talk about things that are deeply painful, and maintain your dignity, and also deal with how people perceive you? It was painful, and nearly 25 years later it is still painful, but you hope from that pain there is a benefit. In the end, I do feel as though I retook control of my life, and I have been able to move forward productively. Things like that happen to people. The key is to understand, even though it changed your life, that you can use it to define your life in ways that are positive.”

Watching Anita, Washington identified with the subject. “I don’t think I’ve had the specific experience of being sexually harassed, but I have had my own experiences with being violated in ways that were out of my control,” she says. She also related, strongly, to the publicity that accompanied Hill’s struggle. “She just wanted to share her truth,” she says, “and as a result, her life never belonged to her in the same way again.”

This empathy extended to the other players in the drama: Joe Biden, for instance, who was then the chairman of the Judiciary Committee and who in the years following the hearing was castigated for decisions he made during the hearing, like asking Hill to repeat some of the more humiliating details over and over (“He said he measured his penis in terms of length”) and giving in to pressure to not hear testimony from three other witnesses. “It’s so easy to think of these people as caricatures,” says Washington, “but what if we don’t? What if we treat them like three-dimensional human beings?” Even Clarence Thomas.

An idea began to form for a movie that would show the events not just from Hill’s side, as the documentary had done, but from the perspective of all three key players: Hill, Thomas, and Biden. “These people are household names now,” she says. “So to figure out what was going on with them back then—what was really happening?”

As it turned out, Susannah Grant, the writer of Erin Brockovich, and Michael London, the producer of Milk, had seen the documentary and were thinking the same thing. When Washington reached out to Grant and London to see if they were interested in working together, she told them, “I don’t want to be a figurehead of a producer. If we do this together, I really need to be a full producer.” Washington adds, “They were like, ‘Do you also want to play her?’ And I was like, ‘Yes.‘”

Washington stuck to her word. “She was a full producer,” says Grant. “She was a full partner in the intention of it, in the vision of it.”

The two of them went to meet Anita Hill. “My thinking was, if they were going to do it, I wanted to put in my two cents,” says Hill. “And I think I had a lot to say, more than two cents’ worth.” Washington listened intently. Still, she agreed with the other producers that the production not take one side.

“The truth is, there are only two people who know what happened, and none of us were interested in making a polemic,” Grant says. As they saw it, “There was no villain in the story. A lot of people remain very angry at Joe Biden, but he’s a human being. And Clarence Thomas was a man who had the greatest opportunity of his life almost taken away from him.”

“What’s meaningful to me about stories,” Washington adds, “is that we can learn from putting ourselves in other people’s shoes.” But when the cameras started rolling, Washington was Hill. She adopted her slightly stooped posture, her measured cadence, her taste in late-’80s unstructured dresses. “Her walk, her mannerisms, just the air around her felt different,” Grant says.

Even now, months after filming, Washington seems to have retained some Hillisms, including long pauses as she collects her thoughts. “I studied her a lot,” she said. “I watched everything you could possibly watch—every interview, every everything. For all of those hours, she’s so graceful; she’s amazing to me.”

Hill isn’t exactly thrilled that the filmmakers chose to show the events as they unfolded and not make a judgment about Thomas’s guilt (or her innocence). “I am not resigned,” she told me with a sigh. “I don’t want to sound superhuman. But what I hope will happen is that people will look at this movie with an open eye, and we can start the conversation again.” And she is impressed with Washington’s performance. “I think she really captured a lot of what I was going through,” she told me. “The turmoil of just trying to be heard, doing what you know is right, and knowing that you don’t necessarily have control over how people are going to respond. It was an emotional roller coaster, and she captures that very well. At 35 years old, I was certainly quite vulnerable, but I wanted to appear dignified, and she captures that.”

Maybe because Washington’s the same way. Back at the Sunset Tower, Washington’s manager arrives to whisk her off to a hotel in Pasadena, where she is presenting Confirmation to an audience of TV critics. In the weeks prior, the media had been giving Washington a hard time: The gossip sites were saying that her marriage was on the rocks because her husband was intimidated by her—the same story they always tell about successful women—and Scandal‘s abortion arc had stirred up conservatives on social media. Despite the efforts to be fair, Washington expects Confirmation will have the same effect—the one aspect of the film’s release that she is not looking forward to. But like Anita Hill, she’s determined to make something positive out of the circumstances. “You don’t like it? Great,” she says, responding to her imaginary critics. “I welcome that conversation.” Gathering her handbag, she purses her lips together with an Olivia Pope–like smile and delivers her zinger: “Because we live in a great country where people get to express their opinions.”