Four years ago, he was just some Swedish kid named Tim who liked messing around on his laptop at home. One iTunes-dominating dance hit (“Levels”) later, he’s Avicii, world’s hottest DJ, making $250,000 a night to keep the Ecstasy-dosed, champagne-soaked masses moving. Jessica Pressler spends a wild week jetting around with Avicii and his Oontz-a-Loompas, and nobody stops partying until they’re rolled out in a wheelchair

Tim Bergling is anxious. He is staring straight ahead, so quiet that everyone with him has gone silent, too, out of respect or maybe a little fear. It was a crazy thing to do, in retrospect, two shows in two different cities, Anaheim and Las Vegas, with only an hour and a half between them. Even with the police escort and the private plane. Now he is twenty-one minutes late, and twenty-one minutes matters when it’s the biggest party night of the year, New Year’s Eve, in the biggest party city in the world, Vegas, and you’re the star of the show, scheduled to go on at midnight, which was—Tim reaches into the pocket of his jeans, barely held up by a Gucci belt, and pulls out his phone to check the time—twenty-two minutes ago. “@Avicii better get to XS soon!!” some douchebag is saying on Twitter. “People paid money for this!” The doors slide open, and Tim steps forward, purposeful as a heart surgeon headed to perform a triple bypass. His girlfriend, his booking agent, his tour manager, a club promoter, a guy with a video camera, and a reporter surge after him.

“Security!” the promoter shouts, and hulking figures fall into step beside us.

“Dog!” An assistant sweeps in to take the Pomeranian from the girlfriend’s arms.

“Okay, go!” and this unwieldy centipede begins its shuffle through the Encore resort, into a restaurant, where bejeweled women and heavyset men look up curiously from their Dover sole, out the back door, past a pool, up some stairs, and behind a velvet rope where Tim alone steps onto a raised platform facing out into the gaping maw of XS nightclub.

He pauses a minute, taking in the expectant faces, flushed and a little drunk, chanting, “A-vi-cii! A-vi-cii! A-vi-cii!”

Then the light falls on him, and he lifts a skinny arm and flicks a switch, flooding the room with a melody that washes over the crowd like a balm before turning into a beat that has them going, his words, “completely apeshit,” and then, and only then, does he relax.

“Happy New Year!” shouts Felix Alfonso, his bodyman, popping open the first of many bottles of Dom Pérignon. When Tim twists around from the jiggy little dance he’s doing behind the decks to accept a glass, he is smiling like the happiest guy in the world.

Which he should be, he knows. Most people would be overjoyed to have Tim Bergling’s life. To have, 250-plus nights a year, audiences of thousands chanting your name. To have the leggy blond girlfriend, the limitless champagne and the piles of money, and famous musicians begging for the production magic he brought to “Levels,” his inescapable 2011 electronic dance music hit in which Etta James has a good feeling, over and over, for three and a half minutes. To have the girls hyperventilating, “I want to fuck him so bad,” whenever he appears, which one blonde is telling her friend right now at high-decibel volume, although Tim can’t hear her, he’s too immersed in cuing up the next track that is going to keep people going completely apeshit.

“I am reasonably happy, I am,” he’d said in his Swedish accent a few days earlier. He rifles a hand through his scraggly blond hair, sincerity in his icy blue eyes. Because he is only 23, subsisting on a diet of Red Bull, nicotine, and airport food, and spending most of his time bathed in the pilated glow of a computer screen has not diminished, just kind of softened, the perpetually rumpled good looks that prompted Ralph Lauren to cast him in an ad campaign. There is a Tumblr devoted to his nose.

“I love DJing, I do,” he stresses. “I love everything that comes with it; it’s fun and it’s kind of glamorous.” And yet. There’s always that moment, right before he goes onstage, when he wonders what the fuck he is even doing up there, if he deserves any of this, and if this is the time it all comes crashing down. “It’s just like when it’s right in the moment and you have that stupid bright light on you,” he says, searching for the words to say it. “It feels so awkward.”

Four days before New Year’s, I arrive in Playa del Carmen, Mexico, to find him pacing around a tented greenroom at Mamita’s Beach Club, smoking like a chimney and knocking back Red Bulls. The champagne is chilling. The waves are lapping gently at the shore. But Tim’s attention is entirely focused on the sounds coming from the stage, where a warm-up DJ is playing a song called “Epic” by Dutch DJs Sandro Silva and Quintino. “I can’t believe he’s playing this,” he mutters.

“This is really frustrating,” he says, grinding out his cigarette and lighting a new one. “Is he gonna play ‘Don’t You Worry Child’ next?”

Felix gives him a warning look and nods in my direction. Vin Diesel bald, with discernible muscle groups, Felix has all the indicia of scariness until he opens his mouth. (“I carry his drugs in my butt,” he later jokes when asked to describe his duties.)

“I’m sorry, I sound grumpy,” Tim says apologetically. “It’s just that it’s embarrassing to do the same things.”

It’s a strange problem for a musician, which is what Tim considers himself to be. While he likes to play mostly his own songs, he still includes tracks by others to keep up the requisite energy level, and “Epic” is one of them. In fact, it’s the third song the opening DJ has played from Tim’s usual rotation, and each time it happens, Tim cracks open another Red Bull and gets a little more jittery.

The Rolling Stones never had to suffer this type of indignity. “We should make a list of songs that we tell festival organizers not to let other DJs play,” Bergling’s tour manager, a no-nonsense Irishwoman named Ciara Davey, says decisively, as if writing a note to self. Tim nods, though he doesn’t seem any less tense. His British lighting guy, Simon Barrington, comes in, carrying a box of equipment and smiling, blithely unaware of the budding crisis.

Tim Bergling, a.k.a. Avicii, DJs 250 nights a year and often earns six figures a show. Do the math.

“How many people are out there?” Tim asks.

“Just twenty-five people,” Simon responds cheerily. “And a dog.”

“And what?” Tim asks distractedly. He’s listening to the thumping sound of “Who” by German producers Tujamo and Plastik Funk coming off the stage. “This, too?” he says incredulously. “How many of my fucking songs is he going to play?”

By the time he’s set to go on, Tim’s face has taken on a grayish sheen. He seems so genuinely convinced this is going to be a disaster that I’m steeling myself for the possibility that his preternaturally brilliant career is about to go up in smoke.

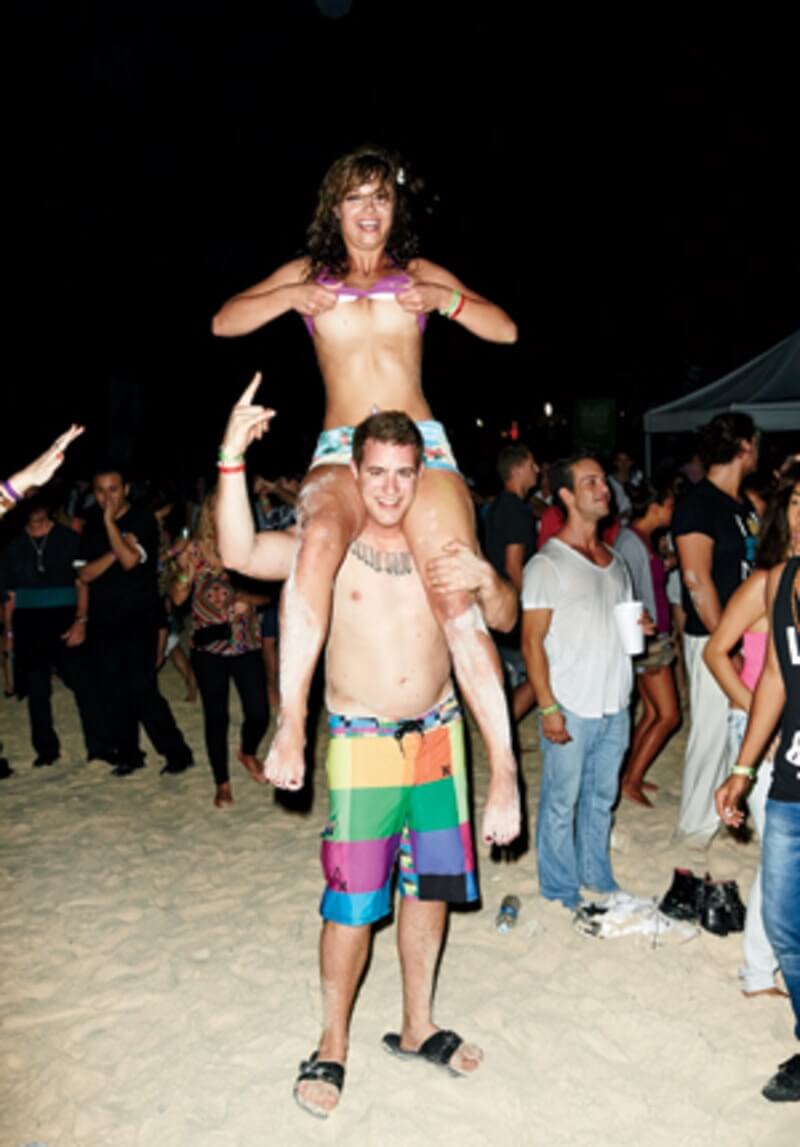

Of course that isn’t what happens at all. First of all, there aren’t twenty-five people on the beach but 2,500. When Tim appears onstage, a tiny figure surrounded by a metropolis of equipment, presses play on his first big hit, “Seek Bromance,” everyone—the California girls in itty-bitty bikinis, sunburned cubicle jockeys, belching frat boys in coral necklaces, ravers with giant pupils—leaps into motion like the sand is on fire, and it becomes immediately clear that his fears were totally unfounded. The DJ before was playing people some songs. Aviciipossesses them. The sound that pours out of the speakers is crisp and melodious and so fucking loud it seems to get inside your body, the bass pounding away at your guts, the synthesizers providing a soaring moment of relief before the bass comes rushing back in so forcefully that there is no room left for thoughts or anxiety or anything. It is not an unpleasant feeling—like being inside a giant, beating heart. Everyone is grinning like a lunatic. In the front row, a fat guy weeps tears of joy. A bra wings through the air, landing somewhere at the side of the stage. Felix spots it from his perch behind the DJ booth, where he has been lighting cigarillos for Tim every time he holds up two fingers or getting him a drink when he makes a C-shaped gesture with his hand. “Women always throw bras,” he yells delightedly.

“How was that?” Tim asks when he gets off the stage two hours later, all shiny and smiley and lighter looking, as though he shed his layer of tension somewhere onstage, in a little heap, like the undergarment Felix had examined and discarded.

“Oh, it was flash,” says Simon, who is clearly used to Tim’s histrionics. “Some people danced. Apparently some guy from Sweden was playing onstage? Not my taste, really.”

later, when I point out as tactfully as I can how completely insane he was to have been nervous, Tim shrugs somewhat abashedly. “It’s just like, you have to really stand out now, DJing,” he says. “Especially now that electronic dance music is getting so big and saturated, and there’s a lot more like similar DJs competing against each other. People are just coming out of nowhere.”

He should know, because Avicii kind of came out of nowhere. Four years ago, Tim Bergling was a high school kid in Stockholm, remixing songs on his laptop in the style of house-music acts like Swedish House Mafia and posting the results in the comments sections of music blogs. While his parents were confounded by the “constant donk-donk thumping” coming out of their youngest son’s bedroom, his ear for melody caught the attention of Ash Pournouri, an ambitious then 26-year-old club promoter who could see the electronic-music boom coming and wanted in on it. Pournouri asked the 18-year-old to coffee, figuring at least he could use his connections to help him get some club gigs. But after Tim warily ambled up, all disheveled-Viking hipster, a grander vision began to take shape. “He started saying all of these things like, ‘I’m going to make you the biggest artist; we’re going to get there in two years; you’re going to be bigger than that guy and that guy,’ ” Tim recalls.

Before Pournouri could make him the biggest DJ in all the land, however, he had to teach him how to DJ, which was something Tim had never actually done before. Thanks to computers, these days, DJing is mostly “before work,” Tim explains. Most of the set list and transitions are worked out before he gets onstage. The notion of a DJ who determines what to play by reading the room “feels like something a lot of older DJs are saying to kind of desperately cling on staying relevant.”

This is not to say there isn’t some skill involved. “I kinda know what’s going to work,” he says, pulling up a screen of cardiogram-like shapes on his laptop, which he identifies as songs. “You have to retain the energy level throughout the set,” he explains, moving the shapes around until they fit together, like Tetris pieces. “You can’t just start out with an energetic song; you have to build up to it.”

Since so much of it is predetermined, I ask, what is he doing onstage? He sure looks busy as hell up there: Twisting knobs and pushing buttons and smiling and dancing. But after watching his show a few times, the only real difference I notice when he twists a button or pushes a knob is that sometimes it gets a little louder or quieter, like he’s deploying all of that energy just to change the volume.

“Yeah, it’s mostly volume,” he shrugs. “Or the faders, when you’re starting to mix into another song, you can hear both in your headphones, you get it to where you want and you pull up the fader.”

The rest of it, the dancing and the constant arm-pumping motion like Right on, doesn’t this moment totally rule? That’s all performance, which was Pournouri’s first lesson.

“A great DJ interacts with the audience,” he says professorially over the phone from Australia, where he recently gave a talk titled “The Avicii Case Study” at the country’s first-ever Electronic Music Conference. “You have to engage people. Dancing, smiling.”

Anyone can play a gang of hits, he goes on. The trick is to make them feel like they’re really at a show. “It sounds very abstract, but a great DJ takes his audience on a journey,” he says. “You want them so into it that they can’t leave. The tracks that get the attention are the songs that create some kind of feeling. And that became a precondition for everything we did in the studio.”

Bergling and Pournouri produced “like a hundred” tracks, and along the way they settled on a kind of formula: a four-chord beat, overlaid with a melody that contains emotionally provocative but universally accessible lyrics. There’s all kinds of stuff layered over it: swirls and echoes and sirens and pauses that make you feel like things are really happening! But the journey, as Pournouri might say, always comes back to the same steady beat. Rob Kapilow, the author of the book What Makes It Great?, likens Avicii’s songs to Muzak, not only because almost all of them riff on other people’s compositions (the piano line repeated throughout “Fade into Darkness,” for instance, is lifted from “Perpetuum Mobile,” by ’80s-era classical music collective Penguin Café Orchestra), but because its main purpose is to create ambience. “It’s peppy, it’s upbeat, it’s got a steady groove,” says Kapilow. “There’s nothing not-smooth about this music, nothing to annoy you. This sort of repetition is very comforting; it’s why children want to hear the same book over and over again.”

Back in Mexico, Tim plays a new track, tentatively titled “Someone Like You.” “It’s so simple,” he says, laughing. “I mean, All my life I have been waiting for someone like you? It’s almost stupid.”

Tim had decided on the DJ name Avici—a friend told him it was a level of Buddhist Hell. (He added the extra i because Avici was already taken on Myspace.) It took him eighteen months to get comfortable behind the decks; his first show ever was in front of 1,000 people. The next thing he knew, he was commanding six figures at clubs in the U.S. and performing at the Ultra Music Festival with Madonna, who had specifically selected him to sherpa her into the booming electronic-dance-music scene. “It was just perfect timing,” Tim says now. “My own rise went hand in hand with the whole EDM rise.”

The last time kids in neon went crazy for electronic music, Things looked a little different. “Back then, no one ever even used to look at the DJ,” says the lighting guy, Simon, who spent four years on tour with the Prodigy in the early ’90s and worked at Gatecrasher, one of the clubs where the rave scene first took off. “It was much more about dancing with one another. Now everyone is facing the stage. They’re all there to see him.”

The big difference: Money. EDM 2.0 isn’t just the province of kids in warehouses and ravers on the beach, it’s the soundtrack of glitzy clubs in places like Las Vegas and Miami, which is where we are headed tonight, as soon as Tim wakes up. “You’ll see it tonight when someone buys a bottle of champagne. There will be sparklers. There will be a variety of scantily clad girls,” says Simon, wrinkling his nose. Because the club has its own lighting, he and Ciara are flying from Mexico to Dallas to prepare for the show there. Which is probably a good thing. “Without digging myself too big a hole,” says Simon, “it’s completely against everything that I personally believe in about clubbing.”

Around midnight, the black SUV carrying Tim, Felix, and myself passes in front of a line of tanned hopefuls being held tantalizingly back by a velvet rope in front of Story, a two-day-old club in Miami Beach. “It’s not really new,” Tim says, yawning. “They just made it over a bunch of times.” These aren’t his favorite kinds of gigs, either. “The VIP crowd tends to be less energetic,” he says. “If you are able to go out and spend $2 million a night in a nightclub and then get laid, it doesn’t add anything for their…what do you call it, what you leave after when you die?” The deep thought stays unfinished as beefy guys in black suits usher us down to a small windowless greenroom, where a dark-haired waitress in dangerous-looking shoes is already pouring glasses of champagne. The booze is always free for Avicii.

In the beginning, this was kind of a problem, when all of a sudden he was Justin Bieber big, without the PG-13 reputation to uphold, hanging out with a crowd for whom every day is literally a party. “You are traveling around, you live in a suitcase, you get to this place, there’s free alcohol everywhere—it’s sort of weird if you don’t drink,” he says. And so he did. At first it was because “I didn’t expect it to last,” Tim says. Then it did last, and soon he had a serious habit: champagne at night, Bloody Marys at the airport, wine on the plane, repeat. “I was so nervous,” he says. “I just got into a habit, because you rely on that encouragement and self-confidence you get from alcohol, and then you get dependent on it.”

He kept going like this until last January, when he developed “like, searing” abdominal pain and wound up in the hospital in New York for eleven days with acute pancreatitis. “I probably drink more now than I should,” he says. “But I have a pace. I never drink two days in a row.”

Tonight is a drinking night, as Tim has friends in town, a rooster-haired gang of Swedes in skinny jeans. “Skål!” they say, downing shots and jabbering excitedly in Swedish, until the room fills with the quiet rustling that signifies the imminent arrival of a famous person. David Grutman, one of the owners of the club, enters accompanied by a small dark figure in a knit cap and sunglasses who is surrounded by an entourage also wearing knit caps and sunglasses. “This is Pharrell,” he announces. Producer Pharrell Williams pauses to shake hands with everyone in his path, like a religious figure or a politician. “I’m happy for your success, man,” he tells Tim, and they chat for a few minutes, literally about the weather, while everyone stares into their champagne glasses. Then it’s time to go.

The DJ booth at Story is elevated above the floor, so the audience below looks like a sea of disembodied hands, and as Tim starts his set—The love you seek and moooore—the hands go crazy, and a beam of emerald light suddenly envelops him, like he’s about to be sucked up into space. Dancers appear, dressed in complicated sex-alien costumes that shoot light out of their fingers. It would all seem very futuristic except for Paris and Nicky Hilton, who are dancing languidly on banquettes as though the past ten years haven’t happened at all. Paris comes to a lot of Avicii’s shows. “She’s like a stalker,” yells Felix, who is standing next to me in the booth. “What?” I yell back. “LIKE A STALKER.” Then he points a giant gun with the word “Avicii,” at me and presses the trigger, spewing a haze of freezing dry ice fog into the air and cackling maniacally. Throughout the night, the line outside stays the same length, but as it goes from 2 a.m. to 3 a.m. to 4 a.m., its denizens seem increasingly skinny and haunted and desperate, so that it looks like a Soviet breadline in Hervé Léger. Upstairs in the balconies, flickering trails of light appear periodically as hostesses in tiny black costumes carry bottles of champagne, each one spiked with a sparkler, signifying the extinguishing of thousands of dollars.

“Last Night was good, right?” says Tim the next day, surrounded by a crime scene of hangover food at the Miami airport. “It was cool that Pharrell came. Though I feel so fucking awkward when someone like Dave is like, ‘Oh, here’s Pharrell.’ And it becomes a thing to say hi. And then we’re like, ‘Oh the weather’s good,’ for twenty minutes. But the energy was pretty good.”

“You only got one bra, though,” Felix points out.

“I know, sucks. It landed on the tempo too. Sped the fucking track up. I didn’t even notice.”

He looks down at his phone. In Tim’s itinerant existence, the Internet is the one place he can reliably be found, and what he sees is not always flattering. “Ha,” he says after a few minutes. A DJ called Funkagenda has posted a long, personal message to Facebook. “It’s like this sob story,” he says. “He’s like ‘I’m an alcoholic, all the shows where I’ve been really drunk I have been sorry for that.’ He just wants people to be like, ‘Oh my god oh poor you, it’s like boo-hoo, it’s stupid.’ ” He turns to me. “If you know who he is, he’s like an asshole,” he explains.

Tim’s beef with Funkagenda started at Coachella, after Tim’s managers had his set time changed so Tim wouldn’t be competing with the holograms of Snoop Dogg and Tupac. “And in order to do that, they had to change everyone else’s set,” he says. “And all these people trash-talked me on Twitter, and Funkagenda was like ‘Oh, that’s like the time he played with Deadmau5, he didn’t have the same production as Deadmau5, so he refused to go out.’ And that’s wrong, I didn’t not want to go out. My management said, ‘We were promised full production and we didn’t get it so we’re not going to play unless we get full production.’ So he starts trash-talking me, like I’m a prima donna, so he’s just a dick.”

“He is a dick,” Felix confirms.

“I thought of the perfect response,” Tim says. “I want to write ‘Cool story bro.’ ”

“Ash isn’t going to like it,” Felix warns.

“It’s very obvious I am being sarcastic if I say ‘Cool Story Bro,’ ” Tim protests, typing.

A few minutes pass. No response. “You’re just sitting there hitting refresh aren’t you?” Felix asks.

“Someone said, ‘Don’t be a dick.’ ” Tim says, laughing uneasily. “It’s not that bad if you are saying ‘Cool Story Bro.’ Is it? It’s funny.” But his confidence is wavering. “I’m going to remove it before it escalates any further,” he mumbles as we board the plane.

Tim does not want to be seen as a dick. He would also like not to care about Internet haters. “The hate started very quickly, because I’m young and I got into it very quickly, and a lot of people just find it hard to be happy,” he says later, sitting at the Joule hotel in Dallas, drinking a cappuccino before his 10 p.m. set. “They get like jealous very easily, maybe. In the beginning, I used to care,” he says. “I don’t really care anymore.”

But in the next breath he’s off talking about how it drives him crazy when people call him a sellout for making a remix for Madonna: “How can you see that as selling out? She is a legend. Like fucking like Michael Jackson, when he was alive, people would have been like, ‘OMG, that’s like selling out.’ Now people would think, ‘Oh, that’s so cool.’ Because he died.”

And the people who gripe about his modeling for Ralph Lauren? “I always wear, like, checkered shirts,” he says, plucking at his flannel. “Well, actually, this is striped, but all the photos are exactly what I usually wear.”

And as for the people who say he is too mainstream: “I have always been mainstream. It’s so weird, because I don’t see it as something negative at all. So many people see it as something negative.”

So yeah, he cares. He knows he shouldn’t. Maybe it’s the Swedish in him. “People in Sweden are very conscious of what people are saying about you,” he says. “That’s what it is. I’m much better about it than I used to be. But it’s hard to switch a button and make it go away, even though I want to, because it’s so stupid.”

There’s another reason, too. “I guess I think like deep inside, I know that it’s like, it’s a different kind of performing, it’s not really… You’re not performing like a guitar player or a singer is performing, you know what I mean? So it’s weird to be in the same type setup as one of those. ‘Cause I’m not really doing much, you know, like technically it’s not that hard.”

He shrugs it off. “You can’t do anything about it,” he says. “I’m where I want to be.”

Another black car to another greenroom, another show: The Lights All Night festival is a blur of kids in Fun Fur and neon going, “Are you rolling?,” mesmerizing one another with light-up gloves. Tim has never taken the Drug Formerly Known As Ecstasy, which is sort of odd since MDMA is to EDM what cocaine was to disco. “I mean, I want to take it,” he says the next day, eating a layover hamburger on the way to Vegas. “But I’m sort of afraid of anything that makes you feel out of control.” Even though the kids in Dallas are his age, it’s hard to imagine him among them crowd-surfing in a neon tankini. “Yeah, I kind of missed all that,” he says. “Because when I was 18, I couldn’t go out, and then when I could go out…” he trails off.

“He gets mobbed,” Felix says.

“I don’t really dance, anyway,” Tim says. Other than his friends from high school, who he sees sparingly—”I help them get laid,” he laughs—most of his time is spent around adults.

“You’re sticking with us through New Year’s Eve?” Felix asks me. “You’ll see what we’re all about.”

“We’ll do some showers,” Tim says.

“We’ll get ten bottles of champagne and we spray it, we have a war,” Felix clarifies, seeing my blank look.

But Tim is having second thoughts. “It’s a bit douchey,” he says. “It’s very douchey.”

“Just blame it on me,” Felix offers magnanimously. “I’ll be a douche.”

New Year’s Eve in Vegas, and the anticipation in the air is palpable. Gangs of twentysomethings rove the hotel with giant water bottles, hydrating. This holiday is an endurance test, it must be trained for. The same is true for Team Avicii. Last night’s show at Marquee and the subsequent hotel suite party was merely practice for tonight’s sprint to Anaheim and back. At 6 p.m., Felix, Tim, and his booking agent, David Brady, gather in the lobby of the Wynn hotel, along with Jared Garcia, a promoter from XS who is coming along to make sure he’ll get back in time, and a camera guy who is filming it all for reasons no one seems clear about.

“Look at the car Jesse bought,” David Brady says on the way to the airport, twisting around from the front seat of the car to show Tim an iPhone picture of the sports car recently purchased by the managing partner at XS. EDM has been good to the clubs: XS made over $80 million last year, according to the Wynn, a figure that broke revenue records.

“Look at Jesse last night,” Tim says, showing the car an iPhone picture of the same promoter, passed out drunk on his couch.

“Did you shave his eyebrows? The rule is when someone gets drunk you shave their eyebrows,” says Felix. “When we get out of the club, let’s go and TP his car,” he adds, as we board the private plane. Everyone agrees this is an awesome idea.

White Wonderland, the festival in Anaheim, is organized by Insomniac, the same people behind the Electric Daisy Carnival, and it is similarly over the top. Four dancers in glittery snowball costumes rush past us on the way to the green room, which is decorated with Christmas lights and contains Emily Goldberg, Tim’s girlfriend. Tall and blonde and startlingly normal, she and Tim started dating exclusively about a year ago, after Tim had his come-to-Jesus moment with his pancreas. (“I used to have a bunch of girls, girls that I liked,” he’d said earlier.) They share a dog, Bear, who is running around on the floor like a feather duster with legs.

“Bear, it’s your daddy,” she says. “I’m not sure she recognizes you.”

Tim scoops the dog up and walks over to the window that looks down at the main floor of the convention center, where rave kids dressed in the event’s requisite all-white are trickling in. “Is it sold out?” he asks.

“About 98 percent,” says David Brady.

“What happened?” he says nervously.

Felix, sensing panic, jumps in. “About 500 people just walked in,” he says. “They’re coming in waves.”

“Wow, people really went all out,” he observes. “Americans are really good at partying,” he says, turning away. “Swedish people would be too cool for this kind of thing. We’re, um…what do you call it? Emily, do you know which word I use?”

“Douchey?” Emily says.

There are 24,000 people there by the time he goes on, and afterward, he is sweaty and giddy. “They were really into that new one, the one that goes, brn-nrew-nrew nrew nrew nrew nam,” he says as the van takes off for LAX, accompanied by a police escort David Brady hired to run all the red lights.

“Faster! Faster!” Tim urges playfully as the van screeches around a curve and everyone laughs. But the mood grinds to a halt at LAX along with the car, which is detained by security. “What the fuck?” he says, peering out at the airport officials sweeping under the car with their flashlights. “Why is this happening?” he demands of Felix. “Didn’t you call ahead?”

Ten minutes later, we’re on the plane, but Tim stays quiet for the rest of the trip, moving the cardiograms of song around on his laptop.

By 2 a.m., XS has given itself over to full New Year’s Eve abandon. Kathy Hilton, Paris’s mom, is dancing on a platform next to the stage, and girls with small dresses and hungry eyes are jammed into the velvet-roped area behind the DJ booth. Felix, who’s been doing his usual business of lighting cigarillos and pouring drinks, has been attempting to keep them away from Tim, but at some point a skinny brunette attached herself to Felix and is hanging from his neck like a scarf. Nearby, Emily is swigging champagne and watching the scene. “Is this totally insane to you?” she types on her phone, showing me the screen. “I see it all the time and I still think it’s completely excessive and disgusting.”

With the brunette in his blind spot, Felix doesn’t notice an XS promoter sneaking up, a bottle of Dom Pérignon in his hand. Seconds later he is batting foam out of his eyes, rivulets of $900 champagne streaming down his bald head, calling for reinforcements. A train of bottle-bearing waitresses marches in like the cavalry.

One hand on his headphones, the other on the fader, Tim is too focused on keeping the crowd jumping in front of him to notice the douchiness going on behind him. He is in what Felix calls “his zone,” where tension and fear and anxiety are obliterated by the pounding of the bass and the swell of the melody, and all that remains is the need to keep it going, to keep the energy up. He lifts a hand in the air, unselfconsciously mouthing the lyrics to his biggest hit:Ooooh sometimes I get a good feeling.

He’s only contracted to play for two hours, but 3 a.m. comes and then 4 a.m., and Tim is still going. He burns through everything in his repertoire, some generic crowd-pleasers, the tracks he’s testing out from the album he’s working on, which will feature real instruments and “a lot of talented people,” he’d said earlier. “Like people with real talent.” He is so successful at making the audience feel like they can’t leave that many of them stay well past the time they should. By four thirty, the girls shimmying on tables have come to resemble Depression-era marathon dancers, all bloody blisters and smeared eye makeup. One of the security guards is taking out a girl doubled over in a wheelchair, puke-stained hair grazing her knees.

Through it all, Tim just keeps shaking his hips and pounding his hand in the air. He doesn’t even see that right behind him, someone has taped Emily’s legs together with electrical tape, leaving her flapping on the platform like a drunk mermaid, a bottle of Dom Pérignon clutched in her hand, or that when she starts to cry, it is Felix who bends down and untapes her. It is 5 a.m., and the air is heavy with exhaustion and sudden sobriety, but Avicii puts on another track, and everyone rallies, as he knows they will. He just isn’t ready for it to end.

Jessica Pressler is a contributing editor for New York magazine.