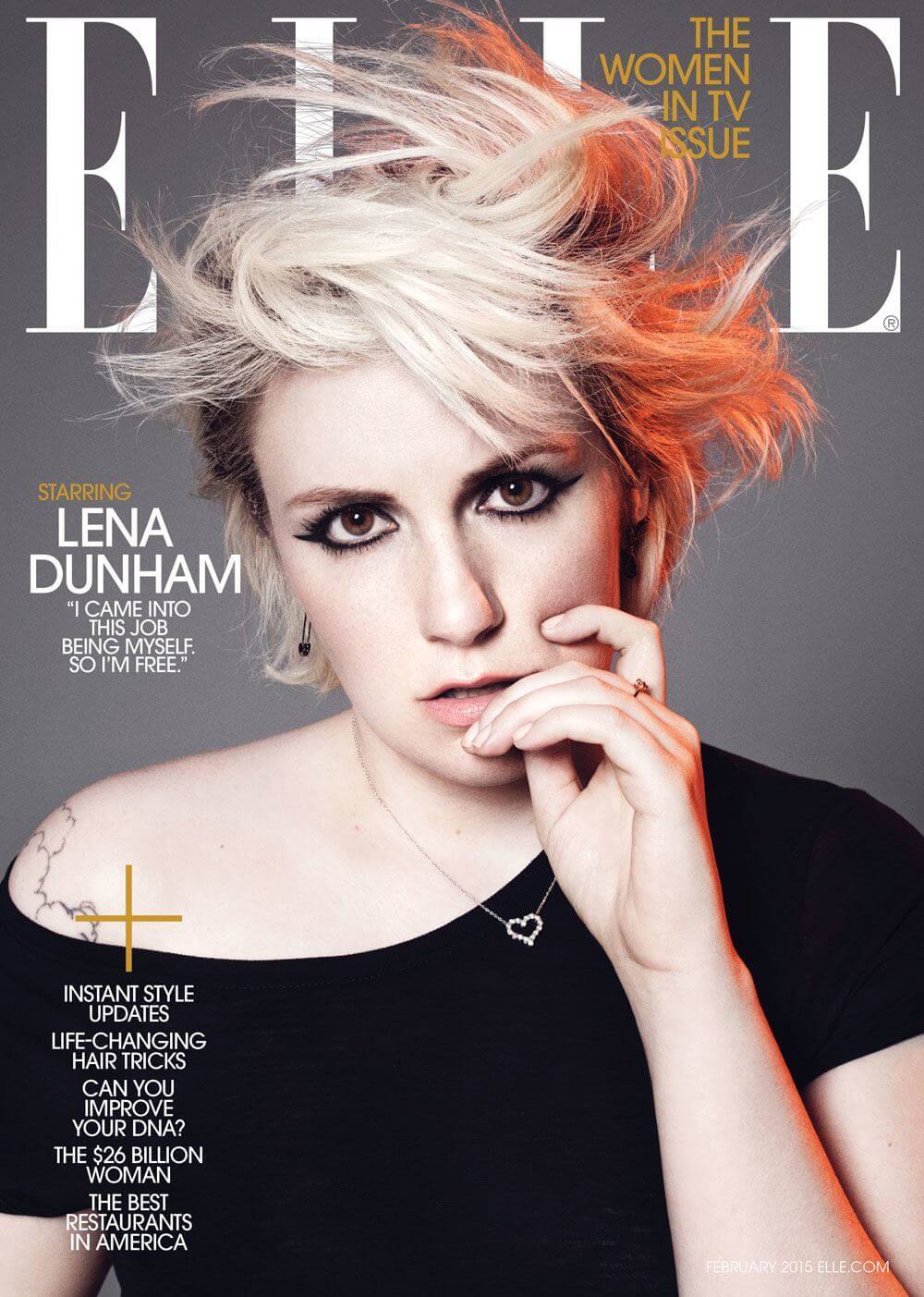

In four years, Lena Dunham springboarded from cable’s freshest voice to full-on cultural icon. Now things are getting really wonderful—and very complicated.

“Question,” Lena Dunham says.

“Do I need to cover up my nipples?” She points to her breasts, which are standing at attention beneath her white turtleneck, and looks expectantly at the group gathered in a small conference room in the Austin office of Planned Parenthood.

There’s a pause as the room considers the question. In most people’s minds, Lena Dunham would be the last person to care about anyone seeing the outline of her areolas. In three seasons of Girls, the HBO show she created, directed, and stars in, her rack has logged so much screen time that it could be considered the show’s fifth girl. But free-boobing it on cable TV and in the great state of Texas are two very different things, and even though Dunham is here to rally the troops against the conservative government’s closing of 80 percent of the state’s abortion clinics, she doesn’t want to be impolite to any member of her audience who might be conservative, sartorially. “I’ll just wear this,” she says finally, tossing her leather jacket over her shoulders.

Lena Dunham is nothing if not polite. This much was obvious from the moment she leapt out of the black SUV delivering her from the airport, a blond ball of smiles and eye contact. “And what’s your daughter’s name?” she asks Ken Lambrecht, the president of Planned Parenthood of Greater Texas, as he toured her around the center. “She is so lucky to have a dad who can educate her about all of this stuff. Two dads! What’s your husband’s name? He’s also a Ken? Two Kens!” Dunham claps her hands together. “I love it!”

Ken One blushes, charmed and maybe a bit surprised. More often than not, people expect Dunham to be like Hannah Horvath, the stunningly self-involved character she plays on Girls. “Which is so weird, especially now,” says Allison Williams, one of the show’s stars. “Hannah is a fuckup who would be incapable of dealing with the first three emails in her inbox. Lena directs and produces a successful television show. A fuckup for her is not remembering the amount of children one of our crew members has.”

As Girls enters its fourth season, Hannah and her friends are only just starting to “make adult choices,” Dunham says. “Like they’ve been kicking and screaming and avoiding committing to relationships, jobs, or going back to school, and they’re finally doing that.” Dunham, on the other hand, made those choices long ago. She was 25 when Girls was picked up by HBO and had to very quickly figure out how to be an artist, a celebrity, and a boss. Girls showrunner Jenni Konner likens her learning curve to Daryl Hannah’s in Splash. “You know where she goes to Bloomingdale’s and learns to speak English from watching television?” she says. “It was like that. I’ve never seen anyone learn so quickly.”

It’s only recently that Dunham feels like she has “become the person she is,” as Hannah might say, personally and professionally. “This was the first season where basically I didn’t walk around every day in terror that I was going to get fired, and that made the experience a lot more pleasant,” she laughs. The new confidence shows in the episodes, which are tighter, funnier, and less digressive, like they were made by, well, an adult. “I feel like we finally fell into a good groove as a creative team, like we had a clear sense of our tone and we didn’t stretch ourselves to do things that weren’t us, and it was like Ahh,” she exhales. At 28, she’s settled into a kind of Brooklyn domesticity with her equally successful and equally neurotic boyfriend, Jack Antonoff of the band Fun., with whom she shares a dog, Lamby. “We’re like a gay couple,” she says happily.

While her on-screen counterpart is still struggling to become “a voice of a generation,” Dunham has realized that dream. Last year, Time decreed her one of its 100 most influential “icons” alongside Malala Yousafzai and Michelle Obama. And The New York Times declared her memoir-in-essays, Not That Kind of Girl, for which she reportedly received a $3.7 million advance, proof that “Dunham can deliver on nearly any platform she chooses.”

“I’ve been in a lucky situation where I came into this job being myself. There was already a certain amount of built-in disdain for what I do. So I’m free.”

If Dunham could, she says, she’d work on Girls forever: “I used to have this thought where we’d have four perfect seasons and disappear in a burst of flames, and now I’m like we should do this until we are 60, and then all the characters should have grandchildren and then we should follow them.” But she’s also eager to try out other platforms. Her production company with Jenni Konner, A Casual Romance, has several documentaries in the works, including one about illustrator Hilary Knight, whose most famous creation, Eloise, “a little feminist rebel nightmare,” Dunham says, is tattooed on her back. When Knight, who is 88, heard about the tattoo, he contacted Dunham, who was fascinated by his story. “It’s interesting to me as an artist what it means to have given a creative legacy to the world but still not feel like you’re done,” she says. “He did Eloise, but he still feels as though he has so much to say outside of that, and he feels a little boxed in by his own success.”

Feeling a little boxed in is part of the reason Dunham decided to use the book tour for Not That Kind of Girl as a platform for Planned Parenthood, not only because she’s passionate about the organization, but because “I want to make clear that the utterly self-involved, politically disengaged character I play on Girls is not who I am,” she told The New York Times. The role of activist is new for Dunham, who told The New Yorker at the start of her career that she was “not a particularly political person.” But things have changed since then. “I realized early on that I was not going to be able to have a comfortable relationship with celebrity if I didn’t feel like I was using it to talk about things that were important to me,” she tells me. “It was always going to make me feel gross, for lack of a better word. I was like, ‘Oh, this attention is something I’m going to figure out how to use in a way that feels productive, healthy, and smart. And not just like as an excuse to collect handbags.’ Although,” she pauses, “I love handbags.”

Dunham’s sister, Grace, who recently graduated from Brown and practically vibrates with the desire to Effect Change, had arranged to have representatives from the organization pass out literature and condoms throughout the 11-city tour, and, as a kind of thank-you, to have Lena participate in a Q&A for employees at the Austin clinic, one of eight remaining places to get an abortion in Texas.

“It is such an honor to be here.” Back at the center, Dunham addresses the crowd of 60 or so men and women with sincere round eyes, then digs into the stack of questions that’s been handed to her. “‘It can be very discouraging to see the protesters that gather outside,'” she reads aloud. “‘What would you do if you were in my shoes?’ I am so sorry,” she says. “I mean, I get upset about Internet commenters, so I can’t imagine how you must feel with actual people screaming.” After the laughter dies down, she turns serious. “I think we’ve all learned that it’s very hard to change the minds of people who aren’t open and willing to grow and don’t have a certain level of decency,” she says. “But I am sure you are doing an amazing job of letting the women who come in here know there are people in this building who care about them, and know that they are guilty of wanting nothing but the best for their families. And I think as long as you continue to convey that, the noise of those protesters gets quieter and quieter. All of that other stuff is just static.”

Afterward, Dunham works the crowd like a career politician, posing for selfies and kissing actual babies. “I’m obsessed with this baby,” she murmurs, clutching a newborn in a Wendy Davis onesie. Then it’s time for the next event, a writing workshop at the Austin Bat Cave, a nonprofit writing and tutoring center across town. Grace lopes alongside her sister, a quiet, bespectacled gazelle, and she scrawls the day’s prompt on a chalkboard in front of the 20 young guests: “Write About a Woman You Love.” The workshop was Grace’s idea, and she lights up when people ask her questions about it. “Personal writing from the perspective of women who have been marginalized is political in and of itself,” she says.

This is something her sister has only recently come to realize about her own work. “In one of the workshops, we asked, ‘Do you feel political?'” Dunham says. “And one of the girls was probably 20 and supersmart, and she said, ‘Yeah. I feel political insofar as my very existence is a political act.’ She’s like, ‘I’m Muslim, I’m queer, I’m a 20-year-old woman; by telling my story I am doing something political.’ And that really resonated for me. Obviously I’m not Muslim, and I’m not queer,” she adds with a laugh, keenly aware that making that kind of comparison is something Hannah might do. “But I’m a woman with a specific set of issues who does not necessarily fit all of the sort of ideals and norms of what society is demanding.”

Dunham’s biography, she is also keenly aware, reads like the setup for a Wes Anderson movie: Her mom, Laurie Simmons, is a well-known photographer; her dad, Carroll Dunham, is a painter of brightly colored nudes with prominent vaginas. She grew up in a loft in Soho, gave vegan dinner parties that were covered by The New York Times, and was baby-sat by the designer Zac Posen. Her specific set of issues, back in the day, were sleep problems, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and a preference for guys that in her book she refers to as “jerks.” And so, like any self-respecting New York City eccentrics, her parents sent her to therapy, which started her on writing and also, perhaps, made her more inquisitive. At parties, her parents would find her in the corner, extracting personal details from their friends. “Lena was really disarming to adults, because she really got down,” her father says. “Like how’s-your-marriage type stuff.”

Often, real-life details from these stories crept into the plays she wrote and performed in at her high school, Saint Ann’s, which encouraged creative expression. “My wife and I would sit there, and it would be a play about an artist having an affair with his assistant,” says Carroll Dunham. “And everyone would look over at us like, ‘Oh my God.'”

Dunham had a quirky sense of humor. Her friend Audrey Gelman likens it to a “fun-house mirror”—the jokes aren’t so much jokes as the truth, exaggerated to comic proportions. Not everyone got it—like when Dunham joked to a classmate, at 17, that she still slept in bed with her parents, and the rumor spread all around school. “We’ve encountered this in the past, where your idea of the funny merges a little too convincingly with the real,” her father warned her, after that. “It’s funny to say, ‘I sleep with my parents,’ but it’s also too close to being massively weird. And you will have to navigate this for the rest of your life.”

When Dunham’s first film came out, the proto-Girls, Tiny Furniture, which features a foundering Hannah-like character who has sex with a chef in a culvert, it fit right in with the squirm-inducing humor popularized by Larry David and Louis C.K. “Like when you see something and you cringe, like, ‘I know that person,'” says Gelman. But when Girls came out, audiences were divided. There were people who loved it, like Murphy Anne Carter, an angelic University of Texas student at the Bat Cave workshop. “Lots of people needed a show likeGirls,” she says. “The stories are very real. There’s none of the fluff, and there’s Porta-Potties and other gross things. Just like, having someone be a goofball and a girl and talking about her period is something that was really missing until Girls came out.”

But there were also people who hated it. Like, really hated it. They had a lot of reasons. They didn’t like the characters, who were too whiny, or too white, or too privileged. They didn’t like the sex, which was too awkward, too weird, too realistic. They didn’t understand, as one TV critic complained to Dunham during a Q&A session, why she had to be naked all the time. “Because it’s a realistic expression of being alive,” she snapped.

“I DIDN’T EXPECT GIRLS TO GET MUCH ATTENTION AT ALL.”

Dunham was unprepared for this kind of response. “I didn’t expect Girls to get much attention at all,” she says. “I mean, we have a very small, very niche-y viewership.” At first, she thought it was her. But then she realized it was something else, something bigger and uglier and more amorphous. “I don’t think it can just be that they hate what my face looks like,” she says. “I think there is an inborn fear from certain men, especially, of women speaking their minds in an unashamed way. Or women are supposed to look great and hate themselves, but they’re not supposed to look bad and like themselves. Like, at times I felt like things that were enraging people were my very ordinariness. Like who the fuck does she think she is to make me listen to this bullshit, when she looks like this and sounds like this?”

If there was a real thing that turned Lena Dunham from apolitical to activist, that may have been it. In 2012, she made a flirty campaign ad for Barack Obama praising him for his stance on birth control, gay marriage, and equal pay for equal work. The ad went viral. And it was then that the right-wing magazine National Review realized Dunham’s success “wasn’t a fluke.”

“If Dunham is indeed reflecting a tectonic shift,” it said in an editorial, “and if … she is the voice of her generation, then one could seriously argue that we’re doomed.”

There were enough people on the other side that she was able to tune out the static. The girls who told her their secrets within five minutes of meeting her. The woman who kissed her head on the airplane. (Although that was a little weird.) Over time, those became the people who mattered. “When she was younger, Lena wrote for personal catharsis,” says Gelman. “But it’s become about making other women feel less alone.”

After the event at the Bat Cave, Dunham looks pale and slightly depleted, like the aliens in the movie Cocoon after they’re drained of their life force. The trouble with being an unusually polite celebrity is that it’s totally freaking exhausting. “I’m trying to figure out the appropriate balance,” she says. “I don’t want to be that person who gives everybody so much there’s nothing left.” To keep up her stamina, Dunham doesn’t drink coffee or alcohol, and she meditates twice a day. “I can also nap anywhere,” she says proudly. “It’s my special skill.” For the tour, she packed a suitcase full of probiotics and vitamins in addition to the SSRI she takes for her OCD. Lately, she’s been really into oregano oil. “It makes you taste like a pizza parlor,” she says. “But it is a natural antibiotic, and it’s literally life changing for me.”

I would probably read her version of Goop.

She and Grace retreat back to their hotel room for showers and a nap before the last event of the night, at Austin’s Central Presbyterian Church. When they arrive an hour before the event, packs of women are lined up around the block. In the greenroom, a library packed with religious tomes, the night’s opening act, local comedian Caroline Bassett, whom Dunham had found in an online talent search, introduces herself. “Oh my God, thank you so much for coming,” Dunham says. “She submitted a video, and my boyfriend and I were dying laughing,” she told the room.

“Oh my God,” said Bassett. “How red am I right now?”

“You look beautiful!” Dunham says. “And your eyeliner is really cool.”

“Your jacket is amazing.”

Soon they’re sitting on the floor, trading pictures of their dogs. “I love your Chiweenie,” Dunham is murmuring when Caren Spruch, from the New York office of Planned Parenthood, comes in, bearing samples of the T-shirts the organization made with Dunham.

“Do you think it looks a little self-aggrandizing?” Dunham says, pulling out a shirt, which is pink and says LENA HEARTS PLANNED PARENTHOOD. The plan is to get some of her famous friends to Instagram themselves wearing the shirts. “We did it this way because I feel like other people would be more comfortable being like, ‘Oh, it’s her thing, it’s not my thing,'” she says. She’s found celebrities can be cautious about aligning themselves with controversial issues. Dunham, on the other hand, feels comfortable putting herself front and center on one of the most hot-button issues in the country. “I’ve been in a lucky situation where I came into this job being myself,” she says. “I don’t have to be scared of, you know, losing my American audience or something. There was already a certain amount of built-in disdain for what I do.” She smiles. “So I’m free.”

Not entirely. A couple of weeks later, I meet Dunham at the health-food restaurant in her neighborhood in Brooklyn, a brown-rice-and-caftans kind of place where she has a house account. Tonight is the last stop on the U.S. leg of the tour. After that, she is scheduled to go to Canada, followed by Europe. “London, Berlin, Amsterdam, and Antwerp,” she says, sounding it out. “Antwerp. That’s one place I have never been before.”

It’s not the only strange terrain she’s navigating. That week she landed on the cover ofNational Review, the headline reading, “The Pathetic Privilege of Lena Dunham.” For the cover story, the author had picked through Not That Kind of Girl, pinpointing one story in particular, in which Dunham recalls a not entirely consensual sexual encounter she had in college. “Dunham’s writing all this is, needless to say, a gutless and passive-aggressive act,” theReview claimed. “She wouldn’t face him in a court of law, but she’ll lynch him in print.”

“Isn’t that crazy?” she says, between bites of artichoke and kale pasta. “That’s the new Republican thing,” she says. “Because they can’t straight-up say, ‘We don’t believe you were raped’ or ‘We believe you deserve to be raped,’ then they’re gonna go with this other tack, where if you don’t report it, you’re an irresponsible woman and you’re not protecting other women. But like, what about if you just want to live an okay life? What if you just want to enjoy yourself and not go to a trial you won’t win for six years? The purpose of the piece wasn’t to drag specific men into the public opinion and examine them; the purpose of the piece was to create a dialogue.”

“Of course, every girl that talks about sexual assault has their credibility questioned,” she says, stirring her tea. “Even though I knew intellectually that’s what happens, it doesn’t fully prepare you for the emotional feeling. But what really angers me is women who haven’t spoken—what if they see that and go, ‘Oh, I’m definitely not saying anything’? That is really painful for me to imagine, the way that I’m being dealt with in the media scaring another woman out of talking.”

The conversation drifts to other things, and eventually she has to leave to take Lamby to the vet. He’s been acting strange, and is really itchy. “Someone recently told me that dogs can be allergic to themselves,” she says. “Which is really dark.”

“I WANT TO RESPOND TO THESE THINGS WITHOUT FEEDING INTO THEM.”

She hasn’t decided what to do about theNational Review situation. “My thing that’s hard is I want to respond to these things without feeding into them,” she says. “Like when I respond, a million more people go and look at the page, feeding the debate. It’s a delicate balance of what you hype up and what you don’t.”

It’s a Tuesday night, and the Brooklyn Academy of Music is packed. “It’s so good to be back in Brooklyn!” Dunham says, wriggling onto a too-high stool and looking out at the crowd, which includes her parents, Grace, and Jack Antonoff, tonight’s opening act. “I’ve actually never read this chapter out loud before,” she says, opening her annotated copy of Not That Kind of Girl: “From the beginning, there was something unknowable about Grace,” she says, and goes on to describe how, as a child, she tried to woo her more standoffish sister with candy and promises to let her watch TV. “Basically, anything a sexual predator might do to woo a small suburban girl I was trying,” she says, with a wry smile. The audience laughs.

The laughs turn into awkward titters as Dunham comes to the part where, at seven, she asked her mom if their vaginas looked the same. “I guess so,” shrugged her mother. But Dunham’s curiosity was not quite sated, and one day, while she and Grace were playing outside, Dunham “leaned down between her legs and carefully spread open her vagina … when I saw what was inside I shrieked,” she reads, going on to explain that her mother came out to retrieve the pebbles Grace had stuffed in there. She then looks out at the audience and says in a tone that acknowledges what a weird kid she was, “This was within the spectrum of things I did.” There’s another wave of laughter and eventually a standing ovation. As the crowd files out, Dunham is mobbed by friends and fans while Grace directs traffic toward the Planned Parenthood tables.

“Aren’t you so glad we came?” I hear the girl next to me say.

“That story about her sister was hilarious,” affirms her friend. “Kids are so weird.”

Not everyone got it. One week later, a conservative website called TruthRevolt published a blog post, “Lena Dunham Describes Sexually Abusing Her Little Sister,” that recast the story as a tale of Dunham “using her little sister at times essentially as a sexual outlet.” This time, Dunham had trouble tuning out the static.

“The right-wing news story that I molested my little sister isn’t just LOL,” she tweeted. “It’s really fucking upsetting and disgusting.”

“And yes,” she clarified. “This is a rage spiral.”

In the volatile atmosphere of the Internet, her rage spiral became a tornado, generating think pieces, cross talk, hashtags, and CNN headlines like “Lena Dunham responds to sexual abuse allegations.” A feminist group petitioned Planned Parenthood to drop Dunham as a spokeswoman. After that, Dunham released a statement worthy of a celebrity who cared about alienating her American audience: “If the situations described in my book have been painful or triggering for people to read, I am sorry,” it read. “I am also aware that the comic use of the term ‘sexual predator’ was insensitive, and I’m sorry for that as well.” Dunham canceled her two final book events, citing health issues. “It wasn’t because of that,” a friend says. “But it didn’t help.” She was, by all accounts, really upset.

But then something started to happen: People started to push back, just like she had done when Girls first started getting criticized. A couple of writers started a Tumblr, Those Kinds of Girls, dedicated to accounts of the oddball stuff they’d done as children. “I used to watch my sister pee, to see ‘where it comes from,'” reads one. “It was painful when it went in my eyes.” A Texas man gave a thought-provoking account to Salon about the terrible three years he spent in prison after he inappropriately touched his sister when she was 8 and he was 12. The man, Josh Gravens, now runs an advocacy group for children who have been put on the sex-offender registry. “You have no idea the amount of awareness she has brought to this issue,” he gushed over the phone. “The biggest problem with this issue is that people don’t talk about it. I’m really sorry that people have used this to try and harm her, but I think it was great she included that story in her book because it really got a conversation started.”

Just like that, there was a dialogue where there hadn’t been one before.

This article appears in the February issue of ELLE magazine.