It was the middle of the night, and Elizabeth Gilbert was curled up in a ball of grief, confusion, and despair. “I found myself in a heap on the couch, around a pillow, huddled and shaking,” the author tells the crowd that has come to see her at Brooklyn’s BRIC House arts center on a recent Sunday. “And I had a sort of out-of-body experience. I saw myself there, shaking and hysterical, and I thought, Okay, we have done this before.”

The audience might have had a similar sense of déjà vu. After all, Gilbert’s ten-year-old memoir, Eat Pray Love, began with a similar scene — the author, lying prostrate on the floor on a cold November night, pleading to the heavens for guidance and hearing, quite out of nowhere, a voice. (“Not an Old Testament Hollywood Charlton Heston voice,” she wrote, but “my own voice, speaking from within my own self.”) Back then, this inner voice prompted Gilbert to take the first steps of an extraordinary journey that led her to this stage: She divorced her husband, sold her possessions, and took off on a yearlong quest for pleasure and spiritual purpose in Italy, India, and Indonesia, countries that coincidentally began with the letter I. “A fairly auspicious sign,” she observed, “on a voyage of self-discovery.” Indeed: Blessed by Oprah at the height of her powers, Eat Pray Love wasn’t just a best seller, it was a juggernaut — which, in case you don’t know, is derived from a Hindi word for the god who sits on a massive cart used in spiritual processions that supposedly crushed the occasional devotee caught in its path — an unstoppable force that drove ideas about Eastern spirituality, gelato, and self-actualization into the minds of over 10 million readers, spawned a Julia Roberts movie, and had a measurable effect on Bali’s GDP. So thoroughly were its themes absorbed into the cultural consciousnesses that even now, the title is used as shorthand to describe any kind of hajj taken by economically secure but emotionally adrift white women in their 30s.

As evidenced by who is at the BRIC today. It’s November 13, 2016, a few days after the election, and the people who have paid $275 apiece to attend a daylong “creativity workshop” with Gilbert and her friend Rob Bell, a pastor and motivational speaker, have instead found themselves attending a kind of group therapy session. As is usual for a Gilbert event, the room is filled with women: women with tote bags, women with designer bags, women with blue hair, women with round glasses, women helpfully informing each other there’s no toilet paper in the last stall. If any of these women voted for Donald Trump, whose election to the highest office in the land was the cause of the breakdown Gilbert is describing, you can’t tell by their tear-stained faces, which are turned toward the stage like plants toward light.

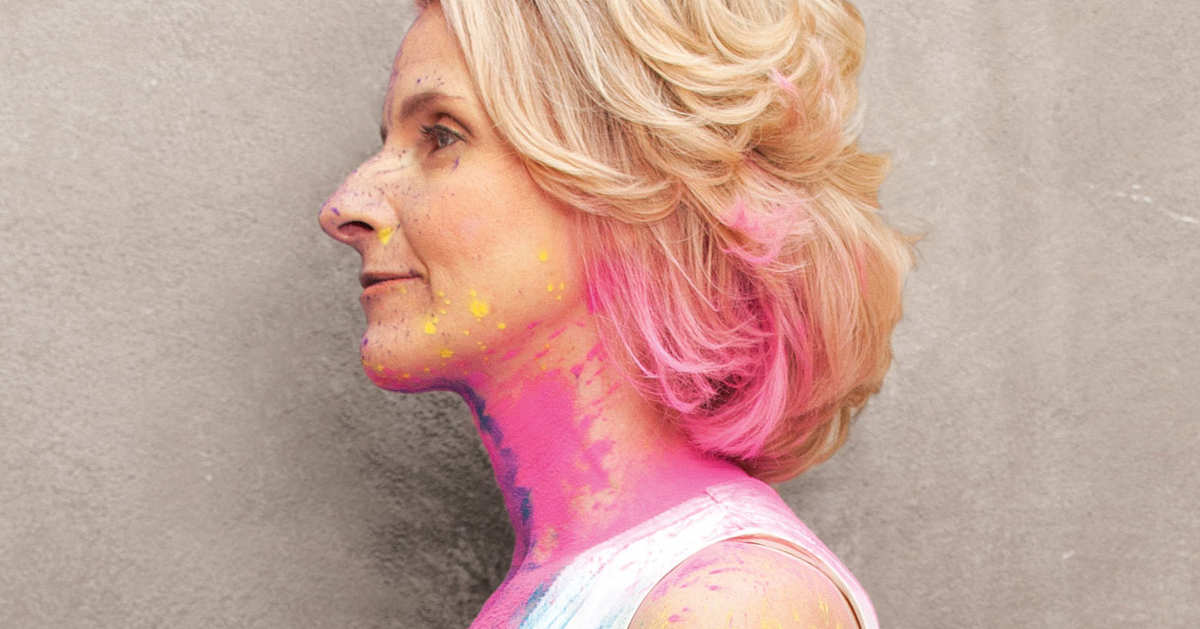

Gilbert, who is tall and blonde with a face as open and friendly as a sunflower, makes a natural guru for the age of aspirational spirituality, though she was slow to take the part after Eat Pray Love. As surprised as anyone by the book’s success, she seemed to see herself as a fiction writer who’d stumbled into a strange land and was unsure how to react to the locals trying to make her their queen. Eventually, despite being an admitted people-pleaser, she backed away gracefully and went off to write more books, a task that turned out to be difficult. As she later put it, it was “exceedingly likely” that her greatest success was behind her.

It took her until 2010 to produce Committed, the sequel, in which her live-in boyfriend, José Nunes, a.k.a. “Felipe,” the suave Brazilian-born Australian who sweeps her off her feet at the end of Eat Pray Love (played by Javier Bardem in the movie), gets caught up in an immigration nightmare only a wedding will solve, and Gilbert, rendered marriage-phobic after her infamously bad divorce, makes peace with her qualms about the institution so that they might live happily ever after. Then, in 2013, she released her first novel in 13 years, the charmingly old-fashionedSignature of All Things, about a 19th-century female botanist.

Maybe it was the novel’s excellent reviews (The New Yorker called it “incandescent”) that enabled Gilbert to breathe easier, because not long after, she seemed to begin to embrace the identity of inspirational figure: She gave her second TED Talk and took to social media, where she presided over a group of fans she calls Dear Ones (as in: “Dear Ones, Try to take it easy on yourselves … You’re all a bunch of hot messes, and you’re all perfect”) and became the Taylor Swift figure in a squad of powerful female writer–motivational speakers who call each other Sister — among them Cheryl Strayed (Wild), Glennon Doyle Melton (Love Warrior), and Brené Brown (Daring Greatly).

“We met at an event where we were both speaking,” Brown tells me of Gilbert. “And we both started laughing because we were wearing the same clogs and the same socks under the clogs.” Last December, the group’s charity, the Compassion Collective, raised $1 million for Syrian refugees. Around the same time, Gilbert released her first straight-ahead self-help book, Big Magic: Creative Living Beyond Fear.

“In my own mind, I think of it more as a manifesto,” Gilbert told me back in October, when I met her in Central Park on an unseasonably warm fall day.

A quasi-mystical how-to guide, Big Magic’s central conceit is that lurking within everyone are “extraordinary treasures” that long to be coaxed out. Gilbert’s advice on how to do so is both specific and vague, from writing a letter to one’s fear to being “open and relaxed” to receive ideas, which in her telling are floating around the universe, waiting to be claimed. Writing the book, she said, was “galvanizing”: “It felt really cool as a woman in my 40s to say, ‘Here is a subject I know a lot about, and here is a subject on which I have earned my authority. This is what I’ve learned from my own experience. This is what I’ve noticed works really well, and this is what I’ve noticed is really destructive. And this is a way of thinking about this that I think is interesting, and this is a way of thinking about this that I think leads to torment. I’ve been doing this for a really long time, I have expertise on this, and here’s my contribution on the subject. And I’m not going to couch it in a bunch of self-deprecating apologies.’ ” Maybe a few. “And if this is helpful to you, you’re welcome to it. Otherwise — you know,” she laughs, “no harsh feelings.”

Gilbert had been circling the idea for Big Magic for 12 years, she says, but she plucked it from the universe at the exact right cultural moment, when words like creative are applied to office-drone-job descriptions to make them sound more interesting and everyone is a “maker,” a word that Gilbert has started using, especially when she’s giving talks at events like an Airbnb conference. Gilbert has worked hard at her public speaking, and it’s paid off. Onstage, she’s funny and warm and wise (although she occasionally drops into a cadence that reminds you ofHillary Clinton at a black church). She wants to do more of it.

“I think I’ve gotten a little bit bored with sitting in a room alone making things,” she told me. “I like dialogue. I like this” — she gestured to the space between us. By then we were sitting at Tavern on the Green, where the food and service are notoriously terrible but the setting unbeatable. Gilbert told me it was one of her favorite places, which is as indicative as anything of her glass-half-full take on life.

Lately, though, this outlook has been tested. “It’s been a hell of a year,” she told the crowd at Marble Collegiate Church on 29th Street in September while promoting Big Magic. Over the summer, Gilbert had announced on Facebook that she was separating from her husband, the beloved character from Eat Pray Love. A few months later, she’d revealed that the split had occurred because she was now in a relationship with a woman, Rayya Elias, whom die-hard fans might recognize as one of her best friends. That wasn’t all. In a tragic twist, Elias had been diagnosed with terminal pancreatic and liver cancer.

And this was before the election. On November 8, as the results rolled in, Gilbert had all the reasons in the world to curl herself into the fetal position. But then, once again, she heard a voice. “As I was looking down at myself curled up on the couch, what came to my mind were these three words,” she tells the crowd at BRIC House. “Create, create, create.”

At age 23, Gilbert showed up at the offices of Spin magazine without an appointment. Eventually, they gave her a freelance assignment, and soon she was out reporting on everything from fur-clad fantasists at a Renaissance fair to the starry-eyed fans of Saved by the Bell. “She was very self-sufficient,” says her then-editor Craig Marks. “Not a diva, no hand-holding needed, you’d just kind of point her in the right direction and let her go. And she was funny.” (“He even smells like cigar smoke over the phone,” Gilbert wrote of the Saved by the Bell producer.) “We were very sad when GQ stole her,” Marks told me.

Gilbert’s best-known piece for GQ is probably “The Muse of the Coyote Ugly Saloon,” a first-person story about her job at the East Village dive, which went on to become a terrible-wonderful movie starring Piper Perabo as a bartender–aspiring songwriter who composes love ballads on the rooftop of a laughably located Manhattan apartment building. But mostly she wrote about men, in particular men who had forged ahead in trying circumstances: a winemaker in war-torn Lebanon; a quadriplegic ex–coke addict; Tom Waits. “I like tough people,” she told me in the park. “Because I’m not one.”

As Eat Pray Love powered through the culture, it also generated a backlash. Regardless of whether they had read it, critics dismissed the book as moony, self-indulgent girl stuff — “chick lit, if you really want to get ghetto,” as Gilbert put it to the Times — and scoffed at the ending, which culminated, if not in a wedding (see above re: the sequel), then in a traditional happy-ending kind of coupling. But Gilbert’s friend and Squad member Glennon Doyle Melton points out that the book was more progressive than many gave it credit for. “A woman leaving her marriage not because she was close to being killed but because she felt like it?” she told me over the phone. “And then going to a country because she wanted to learn the language? That was all, like, very agitating, outside-of-the-box, forward-thinking, counterculture kind of stuff.” Of course, as many pointed out, the Eat Pray Lovejourney was not something just anybody could do — Gilbert was able to only because she had gotten a six-figure book advance.

“Privilege” still comes up in the Q&A session of almost every talk Gilbert gives. “I want to talk about privilege,” one audience member says at the BRIC, although this is the entirety of her question, and it doesn’t lead to a super-interesting discussion. Still, it’s something Gilbert has definitely thought about and formulated a response to: “I think there’s huge validity in acknowledging differences in privilege,” she said in Central Park. “If that conversation is being had in a serious way, then it’s absolutely a valid conversation. But if that conversation is being had as a way of dismissing somebody’s work, it’s a ridiculous conversation. I mean, the most extreme privilege that I inhabit is that I was born as a woman in this moment in history, in this culture,” she went on, in a voice that suggested she was about to go into a sermon. “I’m the first woman in the entire history of my family who had a public voice. I’m the first woman who had autonomy over her body. I’m the first woman who had autonomy over money. My mom was trying to open a checking account in 1974 in Connecticut, when I was 5 years old, and she was told that she couldn’t do it without her husband’s signature. But I guess my question would be ‘What do you want me to do instead? Do you want me to not become a writer? Or do you want me to use my privilege to create the most interesting body of work that I possibly can, to live the broadest possible number of experiences that I can, to reach out to the most number of women who I could reach?’ ”

With her Eat Pray Love windfall, Gilbert and José settled in Frenchtown, New Jersey, a bucolic town on the Delaware River, and began setting up their version of an artists’ colony, persuading friends to move down and, in some cases, offering to finance their creative projects. “All of a sudden I had a huge pile of money,” Gilbert said in the park. “And my idea was, Well, then we shall all have a huge pile of money.” This didn’t always work out well. “In many cases, it just, like, created a kind of petri dish for resentment,” she said. “But it wasn’t universally bad. In about 50 percent of cases it turned out amazing, and people bloomed and made great things.”

One of those people was Rayya Elias, a part-time hairdresser Gilbert met in 2000 when her first marriage was foundering and a friend pushed her to the East Village walk-up Elias was using as a studio. “She had this nasty little ’fro,” Elias later told the Times Magazine. “It looked like Art Garfunkel’s hair.”

The women were polar opposites: Gilbert a prim rule-follower who went to bed “every night at 10 p.m. with a copy of The Atlantic Monthly tucked under my arm,” she later wrote; Elias a “rough diamond,” a “Syrian lesbian, ex-junkie, ex-con, ex–street hustler” who’d been in and out of jail and spent time living on the streets. But they “loved each other from the first.” They grew close during Gilbert’s divorce, and more so after Elias’s in 2008, when Gilbert persuaded her to move to New Jersey, providing her with free rent while Elias wrote a memoir, Harley Loco: A Memoir of Hard Living, Hair, and Post-Punk, From the Middle East to the Lower East Side,which was published in 2013. “A classic, bloodstained love letter to bohemian NYC,” Marks wrote in a cover blurb. “Little did I know,” he says now.

Little did Gilbert know, although the signs were certainly there. Gilbert has “the opposite of a poker face,” a boyfriend tells her in Eat Pray Love — emotions register whether she wants them to or not. This seems also to be true of her writing, and looking back at her work, there were a few things that portended this twist, from her ambivalence about marriage in Committed — which was so fraught and went on for so long that one reviewer expressed surprise that the wedding ever happened — to the essay she wrote for the Times Magazine last year about being a chronic “seduction addict.” (“Relationships overlapped, and those overlaps were always marked by exhausting theatricality: sobbing arguments, shaming confrontations, broken hearts.”) And then there was the interview she and Elias gave to Australia’s Sydney Morning Herald, in which the journalist describes the two friends finishing each other’s sentences. “I know it sounds like a love story,” Elias said then. “And it totally is.”

Still, Gilbert seemed a little shell-shocked in the Facebook post she wrote in September. “Dear Ones,” she began. “In the moment I first learned of Rayya’s diagnosis, a trap door opened at the bottom of my heart (a trap door I didn’t even know was there) and my entire existence fell straight through that door.” In the end, she went on. “I was faced with this truth: I do not merely love Rayya; I am in love with Rayya.”

“Awwwwwww,” the audience responded in September, when Gilbert began her speech at the Marble Collegiate Church by addressing the “very big changes” that had been going on in her personal life. “Divorce, new love, horrible, devastating, heartbreaking news, um, unbelievable, transformative joy, all of it going on at the same time,” as she put it. She and Elias hadn’t been sure that this new chapter was going to be warmly received, she said, but they were grateful for the outpouring of support they got on Facebook. “You are very good souls,” she said.

“Awww,” the audience said again, and the sound of several hundred women awwwing at once reverberated around the Gothic interior like the response to a prayer.

Gilbert didn’t want to say much else about her relationship. “This is a story I am living — not a story that I am telling,” she gently told her Facebook followers, a way of signifying that unlike her friend Melton, who wrote a book about saving her marriage and then essentially live-blogged her divorce (and subsequent relationship with a woman), she was going to keep things closer to her vest. (“Boundaries,” one follower approvingly noted.)

This may come as a surprise to those who see Gilbert as one of the Leading Figures in Overshare, but, “as intimate as Eat Pray Love appears, it’s not my published diaries,” she told me in Central Park. “It’s a chosen and selected and curated combination of anecdotes and stories that I decided were fit for public consumption. By the time it’s presented to you, I’ve lived it, I’ve come out on the other side of it, I’ve been in therapy about it, I’ve had a bunch of editors read it; it’s been processed and processed and processed. This situation that I’m in right now is happening live in my life, and it’s far too soon for me to be putting much out there about it other than the very basic facts. And if there’s something more that I want to say about it later, you’ll hear it from me.”

Still, she can’t help but talk about it a little. “What surprised me was the long period of calmness,” she said with a laugh. “Because that’s atypical. You know? Who’s finished? How can you possibly be done? Like, you’re still going to be interacting with different people every day. The circumstances are going to change, the environment’s constantly in flux, the reality is changing every five minutes. Nobody’s done.”

One thing she’s not doing, she says, is giving herself as hard a time as she did during the breakup of her first marriage. “I’ve cultivated a hard-earned, pretty friendly relationship with myself,” she said. “A sympathetic relationship with myself. Which is not about letting myself off the hook and not holding myself accountable. It’s about this general, like really marrow-deep understanding that it is very hard to be a person. Like, it is not an easy assignment. So you gotta cut yourself some fucking slack. The freight trains come. Like, they come. And anyone who thinks they don’t is kidding themselves. All evidence points to constant freight-train arrival and passage throughout your life. And you fail. And you think you’ve got it sorted out and you don’t. And then you think you’ve got balance and then the rug’s pulled out from under you. And, like, shit tornadoes hit routinely. You know?”

Several weeks later came the kind of shit tornado that would make this fortitude necessary for everyone. On Election Night, Gilbert tells the crowd at BRIC, there was “not a molecule in me that believed” Trump could get elected. But after she heard the voice in her head telling her to create, she got up off the couch. “Can I go on a little rant about this?” she asks Bell.

“Did you have to ask?” he says.

Gilbert stands up. “I feel like we are in radically fertile ground for enormous, revolutionary creativity,” she says, pacing around the stage.

“I’m feeling that emotionally, spiritually, globally, and universally right now. That everything that there was, isn’t. And the situation is going to require you to be new in yourself. I don’t know what that means, but I know that it requires being incredibly awake, very curious, very collaborative, really resistant to any complacency.”

As an example, she cites her partner, Elias. Sickened by the results coming in on Election Night, they decided to turn off the television and light some candles. “I was like, let’s turn off everything that beeps and screams and get really creative right now,” Gilbert says. They decided to pray. Gilbert started off with “a very Liz Gilbert prayer. Like all kinds of squishy, ‘Let us open our hearts to our neighbors and show me how to remain trusting despite the hate and fear, and see the fear in them that is also reflected in me. And let me look for the parts of me that are despotic and judgmental so that I can become blah blah blah blah.’ ”

Then she looked at her partner, the Syrian immigrant ex-junkie ex-con with terminal cancer. She looked back at her. “You done?” Elias asked. Then Elias stood up, looked at the ceiling. “ ‘Fucking seriously?’ ” she shouted, in Gilbert’s telling. “ ‘First you give me cancer, and now you are giving me this? This is how you wanna roll? Then let’s roll. This is how you wanna dance? Let’s dance. You think this is going to make me not live? Watch me live.’ She was just kind of screaming all of it. Cancer. Trump. Injustice. And I’m watching it all, and I’m like, This is amazing,” says Gilbert, who up onstage is starting to shout herself. “Come on! Let’s bring it! Let’s see how alive we can be. Let’s see what we can make now! Not when the world gets better. And everything is fixed and it’s the way we want when we don’t have cancer and we don’t have Trump. What are we going to make now, in this moment? Let’s do this! Let’s fucking do this.”

It’s a new kind of tone for Gilbert, and it’s a little bit awkward. But even though she’s fully using the Hillary Clinton church voice, and the room is so swollen with privilege that you can practically hear Rush Limbaugh cackling about the Bubble and candle-lighting lesbians all the way here in fucking Brooklyn, it somehow works. Where it once felt despairing, the room feels energized. There’s crying and clapping, and from somewhere in the room, a woman who has paid $275 for a creativity workshop yells “Preach!”

*This article appears in the November 28, 2016, issue of New York Magazine.