“Part of the reason we wrote the book is we were really tired of the debate that is going on, is technology good or is it bad,” says Jared Cohen, Google’s chief of ideas, sitting alongside Eric Schmidt, Google’s executive chairman. The company’s unofficial motto is, famously, “Don’t be evil,” which makes their offices above Chelsea Market as good a place as any to discuss the complex moral and political predicaments presented by technology—the subject of Schmidt and Cohen’s new book, The New Digital Age: Reshaping the Future of People, Nations and Business.

“Part of the reason we wrote the book is we were really tired of the debate that is going on, is technology good or is it bad,” says Jared Cohen, Google’s chief of ideas, sitting alongside Eric Schmidt, Google’s executive chairman. The company’s unofficial motto is, famously, “Don’t be evil,” which makes their offices above Chelsea Market as good a place as any to discuss the complex moral and political predicaments presented by technology—the subject of Schmidt and Cohen’s new book, The New Digital Age: Reshaping the Future of People, Nations and Business.

In their pragmatic view, technology is not good or bad, it just is. It’s up to everyone else, from governments and financial institutions to parents, to figure out the most responsible ways to use it. “At this point, I think parents need to talk about data permanence before they talk about sex,” says Cohen, who was 23 when Facebook started. Schmidt, who was not, shakes his head.

“When I think about the shit I did …” he trails off. His co-author blinks in confusion.

They are kind of an odd pair. Schmidt, 58, is an elder statesman of the digital age, the former chief technology officer of Sun Microsystems hired to provide “adult supervision” to Google founders Larry Page and Sergey Brin in the company’s early days. A Google search of his name yields rumors of an unconventional marital arrangement, reports that he can be “arrogant” and “out of touch,” and an unfortunate TV sound bite in which he says that if people don’t like Google street view, they “can just move.”

Schmidt apologized for that last thing, but, as with all digital mishaps, “you cannot get rid of it,” he says. “No one can.”

Cohen’s digital history, on the other hand, is squeaky clean. An indoor-pale 31-year-old with a head full of talking points, Cohen came to Google from the State Department, where he’d earned a reputation as a social-media wunderkind, schooling first Condoleezza Rice and then Hillary Clinton on what the New York Times called “21st-century statecraft,” i.e., teaching them how to do stuff like tweet.

He and Schmidt met in 2009 on a trip to Iraq. “I took a lot of video,” Schmidt says. “And when I got back and played them, all I heard was his voice. I thought, I should talk to him more.”

After nearly ten years as CEO of Google, Schmidt was ready to hand the reins back to Brin and Page (Googling suggests there was some tension), and in Cohen he saw something that reminded him of their early promise. “You will occasionally come across people who are exceptionally talented,” Schmidt says. “In my business, they are often quite odd, but you can sense that their brain processor is just going faster. If you can collaborate with them, something interesting is going to happen, and your life will be very interesting.”

Cohen saw something in Schmidt too. He asked if he would be interested in doing a book, which turned into an article for Foreign Affairs. Schmidt hired him to head a new department, Google Ideas. After that, they became inseparable. “We seem to just do everything together,” says Cohen. In an interview, they mimic each other’s speech patterns, like they were written using the same code.

The pair had no qualms about tackling such a huge topic as “the Future of People, Nations and Business.” “Think about the worlds that we come from,” says Cohen. “Eric comes from the technology world, and I come from the geopolitical world. You need the two areas of expertise, and you need the two generations, and so it works.”

The book lays out what we can expect in the future in excitably wonky detail: driverless cars, holographic “memory rooms,” even “microscopic robots in your circulatory system that keep track of your blood pressure.”

“Don’t think of, you know, robots with scary arms,” says Schmidt. “Think of a digital component inside of you that helps monitor your health. That sounds great to me.”

Not everything they’ve envisioned sounds so great. In the future, as now, the cool technology that makes life more Jetsons-like will just as easily be accessed by villains. Corrupt regimes will use it to repress their citizens. Terrorists will employ it to wreak havoc, and hackers will manipulate it for personal gain. In their telling, the digital realm is a place where good and evil will be forever locked in battle.

To research the book, they spent a year traveling to more than 30 countries. “It was Jared’s idea to do the tour,” says Schmidt. “The argument was, we have to go see.”

In Pakistan, they met women whose faces had been disfigured in acid attacks. “Its hard to understand the kind of evil that is destroying a woman’s face and her eyes in a culture where that guarantees that she could never leave the house for the rest for her life,” says Schmidt. “But the message of hope was, they used the Internet to have a digital life.” In Myanmar, they watched on the Internet as warring factions the next city over ratcheted up violence by spreading false rumors of atrocities committed by the other side. “Each side made up terrible things,” says Schmidt, who gave a speech in Yangon arguing that they should have the right to, since censorship taints the quality of all information.

In some places, there was no Internet at all. “In Kyrgyzstan, the Internet wasn’t working in the hotel,” says Cohen. “But Eric had a wonderfully geeky moment and fixed the entire system. It’s the only time I’ve ever seen him violate his eight-hour-sleep rule.”

In some places, there was no Internet at all. “In Kyrgyzstan, the Internet wasn’t working in the hotel,” says Cohen. “But Eric had a wonderfully geeky moment and fixed the entire system. It’s the only time I’ve ever seen him violate his eight-hour-sleep rule.”

The trip changed Schmidt in other ways, too. “Before, I think I was more techno-determinist,” he says. “People in my position, all you think about is technology. You don’t think about how humans will interact with it.”

Back in the States, Schmidt and Cohen have had no shortage of examples of how technology can be used for good and evil, often in the same instance. You could argue, for instance, that the perpetrators of the Boston Marathon bombings seem to have been radicalized by the Internet, and vigilantes used it to start a virtual witch hunt, so, technology equals bad. But security cameras and other digital technology helped lead to the swift capture of the bombers. So technology also equals good. The 3-D printer? Really cool technology. The guy who published a manual for how to make an untraceable gun on it? “An idiot,” pronounces Schmidt. “Somebody here or somewhere else is going to download this gun and use it to kill people. A lot of people could badly and evilly misuse that information.”

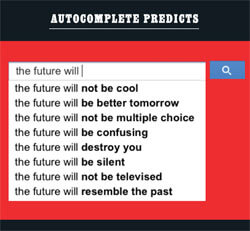

Since they can see the future, they must know: Which side wins, good or evil? “You’ll notice in our book, we don’t go so far as to make recommendations,” says Cohen with millennial caution. “Our goal is to make observations about both the good and the bad, because that’s what the world looks like, with or without technology.”

“Jared, that was not a strong enough answer,” Schmidt says. “The good wins!” he shouts. “In the battle for good and evil, the good wins. I think both of us agree that the number of people who are good is so overwhelmingly larger than the number of people who are bad. Ninety-nine-point-nine-nine of all people are good, well-meaning; it’s just .01 percent. I’m clear that the good wins.”