Rock music used to be a safe haven for degenerates and rebels. Until it found Jesus

Rock music used to be a safe haven for degenerates and rebels. Until it found Jesus

It is wrong to boast, but in the beginning, my plan was perfect.

I was assigned to cover the CrossOver Festival in Lake of the Ozarks, Missouri, three days of the top Christian bands and their backers at an isolated midwestern fairground or something. I’d stand at the edge of the crowd and take notes on the scene, chat up the occasional audience member (“What’s harder—homeschooling or regular schooling”), then flash my pass to get backstage, where I’d rap with the artists themselves “This Christian music—it’s a phenomenon. What do you tell your fans when they ask you why God let Creed break up” The singer could feed me his bit about how all music glorifies Him, when it’s performed with a loving spirit, and I’d jot down every tenth word, inwardly smiling. Later that night, I might sneak some hooch in my rental car and invite myself to lie with a prayer group by their fire, for the fellowship of it. Fly home, stir in statistics. Paycheck.

But as my breakfast time mantra says, I am a professional. And they don’t give out awards for that sort of toetap, Jschool foolishness. I wanted to know what these people are, who claim to love this music, who drive hundreds of miles, traversing states, to hear it live. Then it came, my epiphany I would go with them. Or rather, they would go with me. I would rent a van, a plush one, and we would travel there together, I and three or four hardcore buffs, all the way from the East Coast to the implausibly named Lake of the Ozarks. We’d talk through the night, they’d proselytize at me, and I’d keep my little tape machine working all the while. Somehow I knew we’d grow to like and pity one another. What a story that would make—for future generations.

The only remaining question was how to recruit the willing But it was hardly even a question, because everyone knows that damaged types who are down for whatever’s clever gather in “chat rooms” every night. And among the Jesusy, there’s plenty who are super f’d up. He preferred it that way, evidently.

So I published my invitation, anonymously, at youthontherock.com, and on two Internet forums devoted to the goodlooking Christian poppunk band Relient K, which had been booked to appear at CrossOver. I pictured that guy or girl out there who’d been dreaming in an attic room of seeing, with his or her own eyes, the men of Relient K perform their song “Gibberish” from Two Lefts Don’t Make a Right…But Three Do. How could he or she get there, though Gas prices won’t drop, and Relient K never plays North Florida. Please, Lord, make it happen. Suddenly, here my posting came, like a great light. We could help each other. “I’m looking for a few serious fans of Christian rock to ride to the festival with me,” I wrote. “Male/female doesn’t matter, though you shouldn’t be older than, say, 28, since I’m looking at this primarily as a youth phenomenon.”

They seem like harmless words. Turns out, though, I had failed to grasp how “youth” the phenomenon is. Most of the people hanging out in these chat rooms were teens, and I don’t mean 19, friends, I mean 14. Some of them, I was about to learn, were mere tweens. I had just traipsed out onto the World Wide Web and asked a bunch of 12yearold Christians if they wanted to come for a ride in my van.

It wasn’t long before the little fuckers rounded on me. “Nice job cutting off your email address,” wrote “mathgeek29,” in a tone that seemed not at all Christlike. “I doubt if anybody would give a full set of contact information to some complete stranger on the Internet…. Aren’t there any Christian teens in Manhattan who would be willing to do this”

“Oh, I should hope not,” I blubbered.

A few of the children were credulous. “Riathamus” said, “i am 14 and live in indiana plus my parents might not let me considering it is a stranger over the Internet. but that would really be awsome.” A girl by the name of “LilLoser” even tried to be a friend

I doubt my parents would allow their baby girl to go with some guy they don’t and I don’t know except through email, especially for the amount of time you’re asking and like driving around everywhere with ya…. I’m not saying you’re a creepy petifile, lol, but i just don’t think you’ll get too many people interested… cuz like i said, it spells out “creepy”… but hey—good luck to you in your questy missiony thing. lol.

The luck that she wished me I sought in vain. The Christians stopped chatting with me and started chatting among themselves, warning one another about me. Finally one poster on the official Relient K site hissed at the others to stay away from my scheme, as I was in all likelihood “a 40 year old kidnapper.” Soon I logged on and found that the moderators of the site had removed my post and its lengthening thread of accusations altogether, offering no explanation. Doubtless at that moment they were faxing alerts to a network of moms. I recoiled in dread. I called my lawyer, in Boston, who told me to “stop using computers.”

In the end, the experience inspired in me a distaste for the whole CrossOver Festival, and I resolved to refuse the assignment. I withdrew.

The problem with a flash mag like the Gentlemen’s Quarterly is that there’s always some overachieving assistant, sometimes called Greg, whom the world hasn’t beaten down yet and who, when you phone him, out of courtesy, just to let him know that “the CrossOver thing fell through” and that you’ll be in touch when you “figure out what to do next,” hops on that mystical boon the Internet and finds out that the festival you were planning to attend was in fact not “the biggest one in the country,” as you’d alleged. The biggest one in the country—indeed, in Christendom—is the Creation Festival, inaugurated in 1979, a regular Godstock. And it happens not in Missouri but in ruralmost Pennsylvania, in a green valley, on a farm called Agape. This festival did not end a month ago; it starts the day after tomorrow. Already they are assembling, many tens of thousands strong. But hey—good luck to you in your questy missiony thing. lol.

I made one demand that I not be forced to camp. I’d be given some sort of vehicle with a mattress in it, one of these popups, maybe. “Right,” said Greg. “Here’s the deal. I’ve called around. There are no vans left within a hundred miles of Philly. We got you an RV, though. It’s a twentyninefooter.” Once I reached the place, we agreed (for he led me to think he agreed), I would certainly be able to downgrade to something more manageable.

The reason twentynine feet is such a common length for RVs, I presume, is that once a vehicle gets much longer, you need a special permit to drive it. That would mean forms and fees, possibly even background checks. But show up at any RV joint with your thigh stumps lashed to a skateboard, crazily waving your hooksforhands, screaming you want that twentyninefooter out back for a trip to you ain’t sayin’ where, and all they want to know is Credit or debit, tiny sir

Two days later, I stood in a parking lot, suitcase at my feet. Debbie came toward me. She was a lot to love, with a face as sweet as a birthday cake beneath sprayhardened bangs. She raised a meaty arm and pointed, before either of us spoke. The thing she pointed at was the object about which I’d just been saying, “Not that one, Jesus, okay” It was like something the ancient Egyptians might have left behind in the desert.

“Hi, there,” I said, “Listen, all I need is, like, a camper van or whatever. It’s just me, and I’m going 500 miles…”

She considered me. “Where ya headed”

“To this thing called Creation. It’s, like, a Christianrock festival.”

“You and everybody!” she chirped. “The people who got our vans are going to that same thing. There’s a bunch o’ ya.”

Her coworker Jack emerged—tattooed, squat, graymulleted, spouting open contempt for MapQuest. He’d be giving me real directions. “But first let’s check ‘er out.”

We toured the outskirts of my soontobe mausoleum. It took time. Every single thing Jack said, somehow, was the only thing I’d need to remember. White water, gray water, black water (drinking, showering, le devoir). Here’s your this, never ever that. Grumbling about “weekend warriors.” I couldn’t listen, because listening would mean accepting it as real, though his casual mention of the vast blind spot in the passengerside mirror squeaked through, as did his description of the “extra two feet on each side”—the bulge of my living quarters—which I wouldn’t be able to see but would want to “be conscious of” out there. Debbie followed us with a video camera, for insurance purposes. I saw my loved ones gathered in a mahoganypaneled room to watch this footage; them being forced to hear me say, “What if I never use the toilet—do I still have to switch on the water”

Mike pulled down the step and climbed aboard. It was really happening. The interior smelled of spoiled vacations and amateur porn shoots wrapped in motel shower curtains and left in the sun. I was physically halted at the threshold for a moment. Jesus had never been in this RV.

What should I tell you about my voyage to Creation Do you want to know what it’s like to drive a windmill with tires down the Pennsylvania Turnpike at rush hour by your lonesome, with darting bugeyes and shaking hands; or about Greg’s laughing phone call “to see how it’s going”; about hearing yourself say “no No NO NO!” every time you try to merge; or about thinking you detect—beneath the mysteriously comforting blare of the radio—faint honking sounds, then checking your passengerside mirror only to find you’ve been straddling the lanes for an unknown number of miles (those two extra feet!) and that the line of traffic you’ve kept pinned stretches back farther than you can see; or about stopping at Target to buy sheets and a pillow and peanut butter but then practicing your golf swing in the sportinggoods aisle for a solid twentyfive minutes, unable to stop, knowing that when you do, the twentyninefooter will be where you left her, alone in the side lot, hulking and malevolent, waiting for you to take her the rest of the way to your shared destiny

She got me there, as Debbie and Jack had promised, not possibly believing it themselves. Seven miles from Mount Union, a sign read CREATION AHEAD. The sun was setting; it floated above the valley like a fiery gold balloon. I fell in with a long line of cars and trucks and vans—not many RVs. Here they were, all about me the born again. On my right was a pickup truck, its bed full of teenage girls in matching powder blue Tshirts; they were screaming at a Mohawked kid who was walking beside the road. I took care not to meet their eyes—who knew but they weren’t the same fillies I had solicited days before Their line of traffic lurched ahead, and an old orange Datsun came up beside me. I watched as the driver rolled down her window, leaned halfway out, and blew a long, clear note on a ram’s horn.

Oh, I understand where you are coming from. But that is what she did. I have it on tape. She blew a ram’s horn. Quite capably. Twice. A yearly rite, perhaps, to announce her arrival at Creation.

My turn at the gate. The woman looked at me, then past me to the empty passenger seat, then down the whole length of the twentyninefooter. “How many people in your group” she asked.

I pulled away in awe, permitting the twentyninefooter to float. My path was thronged with excited Christians, most younger than 18. The adults looked like parents or pastors, not here on their own. Twilight was well along, and the still valley air was sharp with campfire smoke. A great roar shot up to my left—something had happened onstage. The sound bespoke a multitude. It filled the valley and lingered.

I thought I might enter unnoticed—that the RV might even offer a kind of cover—but I was already turning heads. Two separate kids said, “I feel sorry for him” as I passed. Another leaped up on the driver’sside step and said, “Jesus Christ, man,” then fell away running. I kept braking—even idling was too fast. Whatever spectacle had provoked the roar was over now The roads were choked. The youngsters were streaming around me in both directions, back to their campsites, like a line of ants around some petty obstruction. They had a disconcerting way of stepping aside for the RV only when its front fender was just about to graze their backs. From my elevated vantage, it looked as if they were waiting just a tenth of a second too long, and that I was gently, forcibly parting them in slow motion.

The Evangelical strata were more or less recognizable from my high school days, though everyone, I observed, had gotten better looking. Lots were dressed like skate punks or in last season’s East Village couture (nondenominationals); others were fairly trailer (rural Baptists or Church of God); there were preps (Young Life, Fellowship of Christian Athletes—these were the ones who’d have the pot). You could spot the stricter sectarians right away, their unchanging antifashion and pale glum faces. When I asked one woman, later, how many she reckoned were white, she said, “Roughly 100 percent.” I did see some Asians and three or four blacks. They gave the distinct impression of having been adopted.

I drove so far. You wouldn’t have thought this thing could go on so far. Every other bend in the road opened onto a whole new cove full of tents and cars; the encampment had expanded to its physiographic limits, pushing right up to the feet of the ridges. It’s hard to put across the sensory effect of that many people living and moving around in the open part family reunion, part refugee camp. A tad militia, but cheerful.

The roads turned dirt and none too wide Hallelujah Highway, Street Called Straight. I’d been told to go to “H,” but when I reached H, two teenage kids in orange vests came out of the shadows and told me the spots were all reserved. “Help me out here, guys,” I said, jerking my thumb, pitifully indicating my mobile home. They pulled out their walkietalkies. Some time went by. It got darker. Then an even younger boy rode up on a bike and winked a flashlight at me, motioning I should follow.

It was such a comfort to yield up my will to this kid. All I had to do was not lose him. His vest radiated a warm, reassuring officialdom in my headlights. Which may be why I failed to comprehend in time that he was leading me up an almost vertical incline—”the Hill Above D.”

I’m not sure which was first the little bell in my spine warning me that the RV had reached a degree of tilt she was not engineered to handle, or the sickening knowledge that we had begun to slip back. I bowed up off the seat and crouched on the gas. I heard yelling. I kicked at the brake. With my left hand and foot I groped, like a person drowning, for the emergency brake (had Jack’s comprehensive howto sesh not touched on its whereabouts). We were losing purchase; she started to shudder. My little guide’s eyes looked scared.

I’d known this moment would come, of course, that the twentyninefooter would turn on me. We had both of us understood it from the start. But I must confess, I never imagined her hunger for death could prove so extreme. Laid out below and behind me was a literal field of Christians, toasting buns and playing guitars, fellowshipping. The aerial shot in the papers would show a long scar, a swath through their peaceful tent village. And that this gigantic psychopath had worked her vile design through the agency of a child—an innocent, albeit impossibly stupid, child…

My memory of the next five seconds is smeared, but logic tells me that a large and perfectly square male head appeared in the windshield. It was blond and wearing glasses. It had wideopen eyes and a Chaucerian West Virginia accent and said rapidly that I should “JACK THE WILL TO THE ROT” while applying the brakes. Some branch of my motor cortex obeyed. The RV skidded briefly and was still. Then the same voice said, “All right, hit the gas on three one, two…”

She began to climb—slowly, as if on a pulley. Some freakishly powerful beings were pushing. Soon we had leveled out at the top of the hill.

There were five of them, all in their early twenties. I remained in the twentyninefooter; they gathered below.

“Thank you,” I said.

“Aw, hey,” shot back Darius, the one who’d given the orders. He talked very fast. “We’ve been doing this all day—I don’t know why that kid keeps bringing people up here—we’re from West Virginia—listen, he’s retarded—there’s an empty field right there.”

I looked back and down at what he was pointing to pastureland.

Jake stepped forward. He was also blond, but slender. And handsome in a feral way. His face was covered in stubble as pale as his hair. He said he was from West Virginia and wanted to know where I was from.

“I was born in Louisville,” I said.

“Really” said Jake. “Is that on the Ohio River” Like Darius, he both responded and spoke very quickly. I said that in fact it was.

“Well, I know a dude that died who was from Ohio. I’m a volunteer fireman, see. Well, he flipped a Chevy Blazer nine times. He was spread out from here to that ridge over there. He was dead as four o’clock.”

“Who are you guys” I said.

Ritter answered. He was big, one of those fat men who don’t really have any fat, a corrections officer—as I was soon to learn—and a former heavyweight wrestler. He could burst a pineapple in his armpit and chuckle about it (or so I assume). Haircut military. Mustache faint. “We’re just a bunch of West Virginia guys on fire for Christ,” he said. “I’m Ritter, and this is Darius, Jake, Bub, and that’s Jake’s brother, Josh. Pee Wee’s around here somewhere.”

“Chasin’ tail,” said Darius disdainfully.

“So you guys have just been hanging out here, saving lives”

“We’re from West Virginia,” said Darius again, like maybe he thought I was thick. It was he who most often spoke for the group. The projection of his jaw from the lump of snuff he kept there made him come off a bit contentious, but I felt sure he was just highstrung.

“See,” Jake said, “well, our campsite is right over there.” With a cock of his head he identified a car, a truck, a tent, a fire, and a tall cross made of logs. And that other thing was…a PA system

“We had this spot last year,” Darius said. “I prayed about it. I said, ‘God, I’d just really like to have that spot again—you know, if it’s Your will.”

I’d assumed that my days at Creation would be fairly lonely and end with my ritual murder. But these West Virginia guys had such warmth. It flowed out of them. They asked me what I did and whether I liked sassafras tea and how many others I’d brought with me in the RV. Plus they knew a dude who died horribly and was from a state with the same name as the river I grew up by, and I’m not the type who questions that sort of thing.

“What are you guys doing later” I said.

Bub was short and solid; each of his hands looked as strong as a trash compactor. He had darker skin than the rest—an olive cast—with brown hair under a camouflage hat and brown eyes and a fullfledged dark mustache. Later he would share with me that friends often told him he must be “part Nword.” He was shy and always looked like he must be thinking hard about something. “Me and Ritter’s going to hear some music,” he said.

“What band is it”

Ritter said, “Jars of Clay.”

I had read about them; they were big. “Why don’t you guys stop by my trailer and get me on your way” I said. “I’ll be in that totally empty field.”

Ritter said, “We just might do that.” Then they all lined up to shake my hand.

While I waited for Ritter and Bub, I lay in bed and read The Silenced Times by lantern light. This was a thin newsletter that had come with my festival packet. It wasn’t really a newsletter; it was publisher’s flackery for Silenced, a new novel by Jerry Jenkins, one of the minds behind the multihundredmilliondollar Left Behind series—twelve books so far, all about what happens after the Rapture, to people like me. His new book was a futuristic job, set in 2047. The dateline on the newsletter read “March 2, 38.” You get it Thirtyseven years have passed since they wiped Jesus from history. The Silenced Times was laid out to look like a newspaper from that coming age.

It was pretty grim stuff. In the year 38, an ancient death cult has spread like a virus and taken over the “United Seven States of America.” Adherents meet in “cell groups” (nice touch a bit of old Commie lingo); they enlist the young and hunger for global hegemony while striving to hasten the end of the world. By the year 34—the time of the last census—44 percent of the population had professed membership in the group; by now the figure is closer to half. This dwarfs any other surviving religious movement in the land. Even the president (whom they mobilized to elect) has been converted. The most popular news channel in the country openly backs him and his policies; and the year’s most talkedabout film is naked propaganda for the cult, but in a darkly brilliant twist, much of the population has been convinced that the media are in fact controlled by…

I’m sorry! That’s all happening now. That’s Evangelicalism. The Silenced Times describes Christians being thrown into jail, driven underground, their pamphlets confiscated. A dude wins an award for ratting out his sister, who was leading a campus Bible study (you know how we do). Jerry Jenkins must blow his royalties on crack. I especially liked the part in The Silenced Times where it reports that antireligion forces have finally rounded up Jenkins himself—in a cave. He’s 97 years old but has never stopped typing, and as they drag him away, he’s bellowing Scripture.

Ritter beat on the door. He and Bub were ready to hear some Jars of Clay. Now that it was night, more fires were going; the whole valley was aromatic. And the sky looked like a tin punch lantern—thousands of stars were out. There were so many souls headed toward the stage, it was hard to walk, though I noticed the crowd tended to give Ritter a wider berth. He kind of leaned back, looking over people’s heads, as if he expected to spot a friend. I asked about his church in West Virginia. He said he and the rest of the guys were Pentecostal, speaking in tongues and all that—except for Jake, who was a Baptist. But they all went to the same “sing”—a weekly Bible study at somebody’s house with food and guitars. Did Ritter think everyone here was a Christian “No, there’s some who probably aren’t saved. With this many people, there has to be.” What were his feelings on that “It just opens up opportunities for witnessing,” he said.

Bub stopped suddenly—a signal that he wished to speak. The crowd flowed on around us for a minute while he chose his words. “There’s Jewish people here,” he said.

“Really” I said. “You mean, Jew Jews”

“Yeah,” Bub said. “These girls Pee Wee brung around. I mean, they’re Jewish. That’s pretty awesome.” He laughed without moving his face; Bub’s laugh was a purely vocal phenomenon. Were his eyes moist

We commenced walking.

I suspect that on some level—say, the conscious one—I didn’t want to be noticing what I noticed as we went. But I’ve been to a lot of huge public events in this country during the past five years, writing about sports or whatever, and one thing they all had in common was this weird implicit enmity that American males, in particular, seem to carry around with them much of the time. Call it a laughable generalization, fine, but if you spend enough late afternoons in stadium concourses, you feel it, something darker than machismo. Something a little wounded, and a little sneering, and just plain ready for bad things to happen. It wasn’t here. It was just…not. I looked for it, and I couldn’t find it. In the three days I spent at Creation, I saw not one fight, heard not one word spoken in anger, felt at no time even mildly harassed, and in fact met many people who were exceptionally kind. I realize they were all of the same race, all believed the same stuff, and weren’t drinking, but there were also 100,000 of them. What’s that about

We were walking past a row of portable toilets, by the food stands. As we came around the corner, I saw the stage, from off to the side. And the crowd on the hill that faced the stage. Their bodies rose till they merged with the dark. “Holy crap,” I said.

Ritter waved his arm like an impresario. He said, “This, my friend, is Creation.”

For their encore, Jars of Clay did a cover of U2’s “All I Want Is You.” It was bluesy.

That’s the last thing I’ll be saying about the bands.

Or, no, wait, there’s this The fact that I didn’t think I heard a single interesting bar of music from the forty or so acts I caught or overheard at Creation shouldn’t be read as a knock on the acts themselves, much less as contempt for the underlying notion of Christians playing rock. These were not Christian bands, you see; these were Christianrock bands. The key to digging this scene lies in that onesyllable distinction. Christian rock is a genre that exists to edify and make money off of evangelical Christians. It’s message music for listeners who know the message cold, and, what’s more, it operates under a perceived responsibility—one the artists embrace—to “reach people.” As such, it rewards both obviousness and maximum palatability (the artists would say clarity), which in turn means parasitism. Remember those perfume dispensers they used to have in pharmacies—”If you like Drakkar Noir, you’ll love Sexy Musk” Well, Christian rock works like that. Every successful crappy secular group has its Christian offbrand, and that’s proper, because culturally speaking, it’s supposed to serve as a standin for, not an alternative to or an improvement on, those very groups. In this it succeeds wonderfully. If you think it profoundly sucks, that’s because your priorities are not its priorities; you want to hear something cool and new, it needs to play something proven to please…while praising Jesus Christ. That’s Christian rock. A Christian band, on the other hand, is just a band that has more than one Christian in it. U2 is the emplar, held aloft by believers and nonbelievers alike, but there have been others through the years, bands about which people would say, “Did you know those guys were Christians I know—it’s freaky. They’re still fuckin’ good, though.” The Call was like that; Lone Justice was like that. These days you hear it about indie acts like Pedro the Lion and Damien Jurado (or P.O.D. and Evanescence—de gustibus). In most cases, bands like these make a very, very careful effort not to be seen as playing “Christian rock.” It’s largely a matter of phrasing Don’t tell the interviewer you’re bornagain; say faith is a very important part of your life. And here, if I can drop the openminded pretense real quick, is where the stickier problem of actually being any good comes in, because a question that must be asked is whether a hardcore Christian who turns 19 and finds he or she can write firstrate songs (someone like Damien Jurado) would ever have anything whatsoever to do with Christian rock. Talent tends to come hand in hand with a certain base level of subtlety. And believe it or not, the Christianrock establishment sometimes expresses a kind of resigned approval of the way groups like U2 or Switchfoot (who played Creation while I was there and had a monster secularradio hit at the time with “Meant to Live” but whose management wouldn’t allow them to be photographed onstage) take quiet pains to distance themselves from any unambiguous Jesusloving, recognizing that this is the surest way to connect with the world (you know that’s how they refer to us, right We’re “of the world”). So it’s possible—and indeed seems likely—that Christian rock is a musical genre, the only one I can think of, that has excellenceproofed itself.

It was late, and the jews had sown discord. What Bub had said was true There were Jews at Creation. These were Jews for Jesus, it emerged, two startlingly pretty high school girls from Richmond. They’d been sitting by the fire—one of them mingling fingers with Pee Wee—when Bub and Ritter and I returned from seeing Jars of Clay. Pee Wee was younger than the other guys, and cute, and he gazed at the girls admiringly when they spoke. At a certain point, they mentioned to Ritter that he would writhe in hell for having tattoos (he had a couple); it was what their people believed. Ritter had not taken the news all that well. He was fairly confident about his position among the elect. There was debate; Pee Wee was forced to escort the girls back to their tents, while Darius worked to calm Ritter. “They may have weird ideas,” he said, “but we worship the same God.”

The fire had burned to glowing coals, and now it was just we men, sitting on coolers, talking latenight hermeneutics blues. Bub didn’t see how God could change His mind, how He could say all that crazy shit in the Old Testament—like don’t get tattoos and don’t look at your uncle naked—then take it back in the New.

“Think about it this way,” I said. “If you do something that really makes Darius mad, and he’s pissed at you, but then you do something to make it up to him, and he forgives you, that isn’t him changing his mind. The situation has changed. It’s the same with the old and new covenants, except Jesus did the making up.”

Bub seemed pleased with this explanation. “I never heard anyone say it like that,” he said. But Darius stared at me gimleteyed across the fire. He knew my gloss was theologically sound, and he wondered where I’d gotten it. The guys had been gracefully dancing around the question of what I believed—”where my walk was at,” as they would have put it—all night.

We knew one another fairly well by now. Once Pee Wee had returned, they’d eagerly showed me around their camp. Most of their tents were back in the forest, where they weren’t supposed to be; the air was cooler there. Darius had located a small stream about thirty yards away and, using his hands, dug out a basin. This was supplying their drinking water.

It came out that these guys spent much if not most of each year in the woods. They lived off game—as folks do, they said, in their section of Braxton County. They knew all the plants of the forest, which were edible, which cured what. Darius pulled out a large piece of cardboard folded in half. He opened it under my face a mess of sassafras roots. He wafted their scent of black licorice into my face and made me eat one.

Then he remarked that he bet I liked weed. I allowed as how I might not not like it. “I used to love that stuff,” he told me. Seeing that I was taken aback, he said, “Man, to tell you the truth, I wasn’t even convicted about it. But it’s socially unacceptable, and that was getting in the way of my Christian growth.”

The guys had put together what I did for a living—though, to their credit, they didn’t seem to take this as a reasonable explanation for my being there—and they gradually got the sense that I found them exotic (though it was more than that). Slowly, their talk became an ecstasy of selfdefinition. They were passionate to make me see what kind of guys they were. This might have grown tedious, had they been any old kind of guys. But they were the kind of guys who believed that God had personally interceded and made it possible for four of them to fit into Ritter’s silver Chevrolet Cavalier for the trip to Creation.

“Look,” Bub said, “I’m a pretty big boy, right I mean, I’m stout. And Darius is a big boy”—here Darius broke in and made me look at his calves, which were muscled to a degree that hinted at deformity; “I’m a freak,” he said; Bub sighed and went on without breaking eye contact—”and you know Ritter is a big boy. Plus we had two coolers, guitars, an electric piano, our tents and stuff, all”—he turned and pointed, turned back, paused—”in that Chevy.” He had the same look in his eyes as earlier, when he’d told me there were Jews. “I think that might be a miracle,” he said.

In their lives, they had known terrific violence. Ritter and Darius met, in fact, when each was beating the shit out of the other in middleschool math class. Who won Ritter looked at Darius, as if to clear his answer, and said, “Nobody.” Jake once took a fishing pole that Darius had accidentally stepped on and broken and beat him to the ground with it. “I told him, ‘Well, watch where you’re stepping,’ ”

Jake said. (This memory made Darius laugh so hard he removed his glasses.) Half of their childhood friends had been murdered—shot or stabbed over drugs or nothing. Others had killed themselves. Darius’s grandfather, greatuncle, and onetime best friend had all committed suicide. When Darius was growing up, his father was in and out of jail; at least once, his father had done hard time. In Ohio he stabbed a man in the chest (the man had refused to stop “pounding on” Darius’s grandfather). Darius caught a lot of grief—”Your daddy’s a jailbird!”—during those years. He’d carried a chip on his shoulder from that.

“You came up pretty rough,” I said.

“Not really,” Darius said. “Some people ain’t got hands and feet.” He talked about how much he loved his father. “With all my heart—he’s the best. He’s brought me up the way that I am.”

“And anyway,” he added, “I gave all that to God—all that anger and stuff. He took it away.”

God had left him enough to get by on. Earlier in the evening, the guys had roughed up Pee Wee a little and tied him to a tree with ratchet straps. Some other Christians must have reported his screams to the staff, because a guy in an orange vest came stomping up the hill. Pee Wee hadn’t been hurt much, but he put on a show of tears, to be funny. “They always do me like that,” he said. “Save me, mister!”

The guy was unamused. “It’s not them you got to worry about,” he said. “It’s me.”

Those were such foolish words! Darius came forward like some hideously fastmoving lizard on a nature show. “I’d watch it, man,” he said. “You don’t know who you’re talking to. This’n here’s as like to shoot you as shake your hand.”

The guy somehow appeared to move back without actually taking a step. “You’re not allowed to have weapons,” he said.

“Is that right” Darius said. “We got a conceal ‘n’ carry right there in the glove box. Mister, I’m from West Virginia—I know the law.”

“I think you’re lying,” said the guy. His voice had gone a bit warbly.

Darius leaned forward, as if to hear better. His eyes were leaving his skull. “How would you know that” he said. “Are you a prophet”

“I’m Creation staff!” the guy said.

All of a sudden, Jake stood up—he’d been watching this scene from his seat by the fire. The fid polite smile on his face was indistinguishable from a leer. “Well,” he said, “why don’t you go somewhere and create your own problems”

I realize that these tales of the West Virginia guys’ occasional truculence might appear to gainsay what I claimed earlier about “not one word spoken in anger,” etc. But look, it was playful. Darius, at least, was performing a bit for me. And if you take into account what the guys have to be on guard for all the time back home, the notable thing becomes how effectively they checked their instincts at Creation.

In any case, we operated with more or less perfect impunity from then on.

This included a lot of very loud, live music between two and three o’clock in the morning. The guys were running their large PA off the battery in Jake’s truck. Ritter and Darius had a band of their own back home, First Verse. They were responsible for the music at their church. Ritter had an angelic tenor that seemed to be coming out of a body other than his own. And Josh was a good guitar player; he had a Les Paul and an effects board. We passed around the acoustic. I had to dig to come up with Christian tunes. I did “Jesus,” by Lou Reed, which they liked okay. But they really enjoyed “Redemption Song.” When I finished, Bub said, “Man, that’s really Christian. It really is.” Darius made me teach it to him; he said he would take it home and “do it at worship.”

Then he jumped up and jogged to the electric piano, which was on a stand ten feet away. He closed his eyes and began to play. I know enough piano to know what good technique sounds like, and Darius played very, very well. He improvised for an hour. At one point, Bub went and stood beside him with his hands in his pockets, facing the rest of us, as if guarding his friend while the latter was in this vulnerable trance state. Ritter whispered to me that Darius had been offered a music scholarship to a college in West Virginia; he went to visit a friend, and a professor heard him messing around on the school’s piano. The dude offered him a full ride then and there. Ritter couldn’t really explain why Darius had turned it down. “He’s kind of our Rain Man,” Ritter said.

At some juncture, I must have taken up my lantern and crept back down the hill, since I sat up straight the next morning, fully dressed in the twentyninefooter. The sound that woke me was a barbaric moan, like that of an army about to charge. Early mornings at Creation were about “Praise and Worship,” a new form of Christian rock in which the band and the audience sing, all together, as loud as they can, directly to God. It gets rather intense.

The guys had told me they meant to spend most of today at the main stage, checking out bands. But hey, fuck that. I’d already checked out a band. Mine was to stay in this trailer, jotting impressions.

It was hot, though. As it got hotter, the light brown carpet started to give off fumes from under its plastic hide. I tumbled out the side hatch and went after Darius, Ritter, and Bub. In the light of day, one could see there were pretty accomplished freaks at this thing a guy in a skirt wearing lace on his arms; a strange little androgynous creature dressed in full cardboard armor, carrying a sword. They knew they were in a safe place, I guess.

The guys left me standing in line at a lemonade booth; they didn’t want to miss Skillet, one of Ritter’s favorite bands. I got my drink and drifted slowly toward where I thought they’d be standing. Lack of food, my filthiness, impending sunstroke These were ganging up on me. Plus the air down here smelled faintly of poo. There were a lot of blazinghot portable toilets wafting miasma whenever the doors were opened.

I stood in the center of a gravel patch between the food and the crowd, sort of gumming the straw, quadriplegically probing with it for stubborn pockets of meltwater. I was a ways from the stage, but I could see well enough. Something started to happen to me. The guys in the band were middleaged. They had blousy shirts and halfhearted arenarock moves from the mid’80s.

What was…this feeling The singer kept grinning between lines, like if he didn’t, he might collapse. I could just make out the words

There’s a higher place to go

(beyond belief, beyond belief),

Where we reach the next plateau,

(beyond belief, beyond belief)…

The straw slipped from my mouth.

“Oh, shit. It’s Petra.”

It was 1988. The guy who brought me in we called Verm (I’ll use people’s nicknames here; they don’t deserve to be dragooned into my memoryvoyage). He was a short, goodlooking guy with a dark ponytail and a devilish laugh, a skater and an expothead, which had got him kicked out of his house a year or so before we met. His folks belonged to this nondenominational church in Ohio, where I went to high school. It was a movement more than a church—thousands of members, even then. I hear it’s bigger now. “Central meeting” took place in an empty warehouse, for reasons of space, but the smaller meetings were where it was at home church (fifty people or so), cell group (maybe a dozen). Verm’s dad said, Look, go with us once a week and you can move back in.

Verm got saved. And since he was brilliant (he became something of a legend at our school because whenever a new foreign student enrolled, he’d sit with her every day at lunch and make her give him language lessons till he was proficient), and since he was about the most artlessly gregarious human being I’ve ever known, and since he knew loads of lost souls from his druggie days, he became a champion evangelizer, a golden child.

I was new and nurturing a transcendent hatred of Ohio. Verm found out I liked the Smiths, and we started swapping tapes. Before long, we were hanging out after school. Then the moment came that always comes when you make friends with a bornagain “Listen, I go to this thing on Wednesday nights. It’s like a Bible study—no, listen, it’s cool. The people are actually really cool.”

They were, that’s the thing. In fifteen minutes, all my ideas about Christians were put to flight. They were smarter than any bunch I’d been exposed to (I didn’t grow up in Cambridge or anything, but even so), they were accepting of every kind of weirdness, and they had that light that people who are pursuing something higher give off. It’s attractive, to say the least. I started asking questions, lots of questions. And they loved that, because they had answers. That’s one of the ways Evangelicalism works. Your average agnostic doesn’t go through life just primed to offer a clear, considered defense of, say, intratextual Scriptural inconsistency. But bornagains train for that chance encounter with the inquisitive stranger. And when you’re a 14yearold carting around some fairly undernourished intellectual ambitions, and a charismatic adult sits you down and explains that if you transpose this span of years onto the Hebrew calendar, and multiply that times seven, and plug in a date from the reign of King Howsomever, then you plainly see that this passage predicts the birth of Christ almost to the hour, despite the fact that the Gospel writers didn’t have access to this information! I, for one, was dazzled.

But also powerfully stirred on a level that didn’t depend on my naïveté. The sheer passionate engagement of it caught my imagination Nobody had told me there were Christians like this. They went at the Bible with gradseminar intensity, week after week. Mole was their leader (short for Moloch; he had started the whole thing, back in the ’70s). He had a wiry, dark beard and a pair of nailgun cobalt eyes. My Russiannovel fantasies of underground gatherings—shared subversive fervor—were flattered and, it seemed, embodied. Here was counterculture, without sad hippie trappings.

Verm hugged me when I said to him, in the hallway after a meeting, “I think I might believe.” When it came time for me to go all the way—to “accept Jesus into my heart” (in that timehonored formulation)—we prayed the prayer together.

Three years passed. I wad strong in spirit. Verm and I were sort of heading up the high school end of the operation now. Mole had discovered (I had discovered, too) that I was good with words, that I could talk in front of people; Verm and I started leading Bible study once a month. We were saving souls like mad, laying up treasure for ourselves in heaven. I was never the recruiter he was, but I grasped subtlety; Verm would get them there, and together we’d start on their heads. Witnessing, it’s called. I had made some progress socially at school, which gave us access to the popular crowd; in this way, many were brought to the Lord. Verm and I went to conferences and on “study retreats”; we started taking classes in theology, which the group offered—free of charge—for promising young leaders. And always, underneath but suffusing it all, there were the cellgroup meetings, every week, on Friday or Saturday nights, which meant I could stay out till morning. (My Episcopalian parents were thoroughly mortified by the whole business, but it’s not easy telling your kid to stop spending so much time at church.)

Cell group was typically held in somebody’s dining room, somebody pretty high up in the group. You have to understand what an honor it was to be in a cell with Mole. People would see me at central meeting and be like, “How is that, getting to rap with him every week” It was awesome. He really got down with the Word (he had a wonderful old hippie way of talking; everything was something action “time for some fellowship action…let’s get some chips ‘n’ salsa action”). He carried a heavy “study Bible”—no King James for the nondenominationals; too many inaccuracies. When he cracked open its handtooled leather cover, you knew it was on. And no joke The brother was gifted. Even handicapped by the relatively pedestrian style of the New American Standard version, he could twist a verse into your conscience like a bone screw, make you think Christ was standing there nodding approval. The prayer session alone would last an hour. Afterward, there was always a fire in the backyard. Mole would sit and whack a machete into a chopping block. He smoked cheap cigars; he let us smoke cigarettes. The guitar went around. We’d talk about which brother was struggling with sin—did he need counsel Or about the end of the world It’d be soon. We had to save as many as we could.

I won’t inflict on you all my reasons for drawing away from the fold. They were clichéd, anyway, and not altogether innocent. Enough to say I started reading books Mole hadn’t recommended. Some of them seemed pretty smart—and didn’t jibe with the Bible. The defensive theodicy he’d drilled into me during those nights of heady egesis developed cracks. The hell stuff I never made peace with it. Human beings were capable of forgiving those who’d done them terrible wrongs, and we all agreed that human beings were maggots compared with God, so what was His trouble, again I looked around and saw people who’d never have a chance to come to Jesus; they were too badly crippled. Didn’t they deserve—more than the rest of us, even—to find His succor, after this life

Belief and nonbelief are two giant planets, the orbits of which don’t touch. Everything about Christianity can be justified within the context of Christian belief. That is, if you accept its terms. Once you do, your belief starts modifying the data (in ways that are themselves defensible, see), until eventually the data begin to reinforce belief. The precise moment of illogic can never be isolated and may not exist. Like holding a magnifying glass at arm’s length and bringing it toward your eye Things are upside down, they’re upside down, they’re right side up. What lay between If there was something, it passed too quickly to be observed. This is why you can never reason true Christians out of the faith. It’s not, as the adage has it, because they were never reasoned into it—many were—it’s that faith is a logical door which locks behind you. What looks like a line of thought is steadily warping into a circle, one that closes with you inside. If this seems to imply that no apostate was ever a true Christian and that therefore, I was never one, I think I’d stand by both of those statements. Doesn’t the fact that I can’t write about my old friends without an apologetic tone just show that I never deserved to be one of them

The break came during the winter of my junior year. I got a call from Verm late one afternoon. He’d promised Mole he would do this thing, and now he felt sick. Sinus infection (he always had sinus infections). Had I ever heard of Petra Well, they’re a Christian

rock band, and they’re playing the arena downtown. After their shows, the singer invites anybody who wants to know more about Jesus to come backstage, and they have people, like, waiting to talk to them.

The promoter had called up Mole, and Mole had volunteered Verm, and now Verm wanted to know if I’d help him out. I couldn’t say no.

The concert was upsetting from the start; it was one of my first encounters with the other kinds of Evangelicals, the handwavers and the weepers and all (we liked to keep things “sober” in the group). The girl in front of me was signing all the words to the songs, but she wasn’t deaf. It was just horrifying.

Verm had read me, over the phone, the pamphlet he got. After the first encore, we were to head for the witnessing zone and wait there. I went. I sat on the ground.

Soon they came filing in, the seekers.

I don’t know what was up with the ones I got. I think they may have gone looking for the restroom and been swept up by the stampede. They were about my age and wearing hooded brown sweatshirts—mouths agape, eyes empty. I asked them the questions What did they think about all they’d heard Were they curious about anything Petra talked about (There’d been lots of “talks” between songs.)

I couldn’t get them to speak. They stared at me like they were waiting for me to slap them.

This was my opening. They were either rapt or retarded, and whichever it was, Christ called on me to lay down my testimony.

The sentences wouldn’t form. I flipped though the list of dogmas, searching for one I didn’t essentially think was crap, and came up with nothing.

There might have ensued a nauseating silence, but I acted with an odd decisiveness to end the whole experience. I asked them if they wanted to leave—it was an all but rhetorical question—and said I did, too. We walked out together.

I took Mole and Verm aside a few nights later and told them my doubts had overtaken me. If I kept showing up at meetings, I’d be faking it. That was an insult to them, to God, to the group. Verm was silent; he hugged me. Mole said he respected my reasons, that I’d have to explore my doubts before my walk could be strong again. He said he’d pray for me. Unless he’s undergone some radical change in character, he’s still praying.

Statistically speaking, my bout with Evangelicalism was probably unremarkable. For white Americans with my socioeconomic background (middle to uppermiddle class), it’s an experience commonly linked to one’s teens and moved beyond before one reaches 20. These kids around me at Creation—a lot of them were like that. How many even knew who Darwin was They’d learn. At least once a year since college, I’ll be getting to know someone, and it comes out that we have in common a high school “Jesus phase.” That’s always an excellent laugh. Except a phase is supposed to end—or at least give way to other phases—not simply expand into a long preoccupation.

Bless those who’ve been brainwashed by cults and sent off for deprogramming. That makes it simple You put it behind you. But this group was no cult. They persuaded; they never pressured, much less threatened. Nor did they punish. A guy I brought into the group—we called him Goog—is still a close friend. He leads meetings now and spends part of each year doing pro bono dental work in Cambodia. He’s never asked me when I’m coming back.

My problem is not that I dream I’m in hell or that Mole is at the window. It isn’t that I feel psychologically harmed. It isn’t even that I feel like a sucker for having bought it all. It’s that I love Jesus Christ.

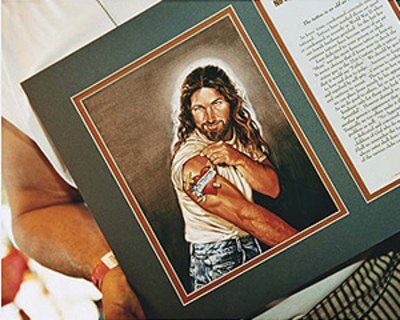

“The latchet of whose shoes I am not worthy to unloose.” I can barely write that. He was the most beautiful dude. Forget the Epistles, forget all the bullying stuff that came later. Look at what He said. Read The Jefferson Bible. Or better yet, read The Logia of Yeshua, by Guy Davenport and Benjamin Urrutia, an unadorned translation of all the sayings ascribed to Jesus that modern scholars deem authentic. There’s your man. His breakthrough was the aestheticization of weakness. Not in what conquers, not in glory, but in what’s fragile and what suffers—there lies sanity. And salvation. “Let anyone who has power renounce it,” he said. “Your father is compassionate to all, as you should be.” That’s how He talked, to those who knew Him.

Why should He vex me Why is His ghost not friendlier Why can’t I just be a good Enlightenment child and see in His life a sustaining example of what we can be, as a species

Because once you’ve known Him as God, it’s hard to find comfort in the man. The sheer sensation of life that comes with a total, allpervading notion of being—the pulse of consequence one projects onto even the humblest things—the pull of that won’t slacken.

And one has doubts about one’s doubts.

“d’ye hear that mountain lion last night”

It was dark, and Jake was standing over me, dressed in camouflage. I’d been hunched over on a cooler by the ashes for a number of hours, waiting on the guys to get back from wherever they’d gone.

I told him I hadn’t heard anything. Bub came up from behind, also in camo. “In the middle of the night,” he said. “It woke me up.”

Jake said, “It sounded like a baby crying.”

“Like a little bitty baby,” Bub said.

Jake was messing with something at my feet, in the shadows, something that looked alive. Bub dropped a few logs onto the fire and went to the Chevy for matches.

I sat there trying to see what Jake was doing. “You got that lantern” he said. It was by my feet; I switched it on.

He started pulling frogs out of a poke. One after another. They strained in his grip and lashed at the air.

“Where’d you get those” I asked.

“About half a mile that way,” he said. “It ain’t private property if you’re in the middle of the creek.” Bub laughed his high expressionless laugh.

“These ain’t too big,” Jake said. “In West Virginia, well, we got ones the size of chickens.”

Jake started chopping their bodies in half. He’d lean forward and center his weight on the hand that held the knife, to get a clean cut, tossing the legs into a frying pan. Then he’d stab each frog in the brain and flip the upper parts into a separate pile. They kept twitching, of course—their nerves. Some were a little less dead than that. One in particular stared up at me, gulping for air, though his lungs were beside him, in the grass.

“Could you do that one in the brain again” I said. Jake spiked it, expertly, and grabbed for the next frog.

“Why don’t you stab their brains before you take off the legs” I asked.

He laughed. He said I cracked him up.

Darius, when he got back, made me a cup of hot sassafras tea. “Drink this, it’ll make you feel better,” he told me. I’d never said I felt bad. Jake lightly sautéed the legs in butter and served them to me warm. “Eat this,” he said. The meat was so tender, it all but dissolved on my tongue.

Pee Wee came back with the Jews, who were forced to tell us a second time that we were damned. (Leviticus 1112, “Whatsoever hath no fins nor scales in the waters, that shall be an abomination unto you.”) Jake, when he heard this, put on a show, making the demifrogs talk like puppets, chewing the legs with his mouth wide open so all could see the meat.

The girls ran off again. Pee Wee went after them, calling, “Come on, they’re just playin’!”

Darius peered at Jake. He looked not angry but saddened. Jake said, “Well, if he wants to bring them girls around here, they oughtn’t to be telling us what we can eat.”

“Wherefore, if meat make my brother to offend,” Darius said, “I will eat no flesh while the world standeth.”

“First Corinthians,” I said.

“813,” Darius said.

I woke without having slept—that evil feeling—and lay there steeling myself for the strains of Praise and Worship. When it became too much to wait, I boiled water and made instant coffee and drank it scalding from the lid of the peanutbutter jar. My body smelled like stale campfire. My hair had leaves and ash and things in it. I thought about taking a shower, but I’d made it two days without so much as acknowledging any of the twentyninefooter’s systems; it would have been stupid to give in now.

I sat in the driver’s seat and watched, through tinted glass, little clusters of Christians pass. They looked like people anywhere, only gladder, more selfcontained. Or maybe they just looked like people anywhere. I don’t know. I had no pseudoanthropological moxie left. I got out and wandered. I sat with the crowd in front of the stage. There was a redheaded Christian speaker up there, pacing back and forth. Out of nowhere, he shrieked, “MAY YOU BE COVERED IN THE ASHES OF YOUR RABBI JESUS!” If I were to try to convey to you how loudly he shrieked this, you’d think I was playing wordy games.

I was staggering through the food stands when a man died at my feet. He was standing in front of the funnelcake window. He was big, in his early sixties, wearing shorts and a shortsleeve buttondown shirt. He just…died. Massive heart attack. I was standing there, and he fell, and I don’t know whether there’s some primitive zone in the brain that registers these things, but the second he landed, I knew he was gone. The paramedics jumped on him so fast, it was weird—it was like they’d been waiting. They pumped and pumped on his chest, blew into his mouth, ran IVs. The ambulance showed up, and more equipment appeared. The man’s broad face had that slightly disgruntled look you see on the newly dead.

Others had gathered around; some thought it was all a show. A woman standing next to me said bitterly, “It’s not a show. A man has died.” She started crying. She took my hand. She was small with silver hair and black eyebrows. “He’s fine, he’s fine,” she said. I looked at the side of her face. “Just pray for his family,” she said. “He’s fine.”

I went back to the trailer and had, as the ladies say where I’m from, a colossal fucking gotopieces. I kept starting to cry and then stopping myself, for some reason. I felt nonsensically raw and lonely. What a dickhead I’d been, thinking the trip would be a lark. There were too many ghosts here. Everyone seemed so strange and so familiar. Plus I suppose I was starving. The frog meat was superb but meager—even Jake had said as much.

In the midst of all this, I began to hear, through the shell of the twentyninefooter, Stephen Baldwin giving a talk on the Fringe Stage—that’s where the “edgier” acts are put on at Creation. If you’re shaky on your Baldwin brothers, he’s the vaguely troglodytic one who used to comb his bangs straight down and wear dusters. He’s come to the Lord—I don’t know if you knew. I caught him on cable a few months ago, some religious talk show. Him and Gary Busey. I don’t remember what Baldwin said, because Busey was saying shit so weird the host got nervous. Busey’s into “generational curses.” If you’re wondering what those are, too bad. I was bornagain, not raised on meth.

Baldwin said many things; the things he said got stranger and stranger. He said his Brazilian nanny, Augusta, had converted him and his wife in Tucson, thereby fulfilling a prophecy she’d been given by her preacher back home. He said, “God allowed 9/11 to happen,” that it was “the wrath of God,” and that Jesus had told him to share this with us. He also said the Devil did 9/11. He said God wanted him “to make gnarly cool Christian movies.” He said that in November we should vote for “the man who has the greatest faith.” The crowd lost it; it seemed like the trailer might shake.

When Jake and Bub beat on the door, I’d been in there for hours, rereading The Silenced Times and the festival program. In the program, it said the candlelighting ceremony was tonight. The guys had told me about it—it was one of the coolest things about Creation. Everyone gathered in front of the stage, and the staff handed out a candle to every single person there. The media handlers said there was a lookout you could hike to, on the mountain above the stage. That was the way to see it, they said.

When I opened the door, Jake was waving a newspaper. Bub stood behind him, smiling big. “Look at this,” Jake said. It was Wednesday’s copy of The Valley Log, serving Southern Huntingdon County—”It is just a rumor until you’ve read it in The Valley Log.”

The headline for the week read MOUNTAIN LION NOT BELIEVED TO BE THREAT TO CREATION FESTIVAL CAMPERS.

“Wha’d we tell you” Bub said.

“At least it’s not a threat,” I said.

“Well, not to us it ain’t,” Jake said.

I climbed to their campsite with them in silence. Darius was sitting on a cooler, chin in hands, scanning the horizon. He seemed meditative. Josh and Ritter were playing songs. Pee Wee was listening, by himself; he’d blown it with the Jewish girls.

“Hey, Darius,” I said.

He got up. “It’s fixin’ to shower here in about ten minutes,” he said.

I went and stood beside him, tried to look where he was looking.

“You want to know how I know” he said.

He explained it to me, the wind, the face of the sky, how the leaves on the tops of the sycamores would curl and go white when they felt the rain coming, how the light would turn a certain “dead” color. He read the landscape to me like a children’s book. “See over there,” he said, “how that valley’s all misty It hasn’t poured there yet. But the one in back is clear—that means it’s coming our way.”

Ten minutes later, it started to rain, big, soaking, percussive drops. The guys started to scramble. I suggested we all get into the trailer. They looked at each other, like maybe it was a sketchy idea. Then Ritter hollered, “Get ‘er done!” We all ran down the hillside, holding guitars and—in Josh’s case—a skillet wherein the fried meat of some woodland creature lay ready to eat.

There was room for everyone. I set my lantern on the dining table. We slid back the panes in the windows to let the air in. Darius did card tricks. We drank spring water. Somebody farted; the conversation about who it had been lasted a good twenty minutes. The rain on the roof made a solid drumming. The guys were impressed with my place. They said I should fence it. With the money I’d get, I could buy a nice house in Braxton County.

We played guitars. The RV rocked back and forth. Jake wasn’t into Christian rock, but as a good Baptist he loved old gospel tunes, and he called for a few, God love him. Ritter sang one that killed me. Also, I don’t know what changed, but the guys were up for secular stuff. It turned out that Pee Wee really loved Neil Young; I mean, he’d never heard Neil Young before, but when I played “Powderfinger” for him, he sort of curled up like a kid, then made me play it again when I was done. He said I had a pretty voice.

We all told each other how good the other ones were, how everybody else should really think about a career in music. Josh played “Stairway to Heaven,” and we got loud, singing along. Darius said, “Keep it down, man! We don’t need everybody thinking this is the sin wagon.”

The rain stopped. It was time to go. Two of the guys had to leave in the morning, and I needed to start walking if I meant to make the overlook in time for the candlelighting. They went with me as far as the place where the main path split off toward the stage. They each embraced me. Jake said to call them if I ever had “a situation that needs clearing up.” Darius said God bless me, with meaning eyes. Then he said, “Hey, man, if you write about us, can I just ask one thing”

“Of course,” I said.

“Put in there that we love God,” he said. “You can say we’re crazy, but say that we love God.”

The climb was long and steep. At the top was a thing that looked like a backyard deck. It jutted out over the valley, commanding an unobstructed view. Kids hung all over it like lemurs or something.

I pardoned my way to the edge, where the cliff dropped away. It was dark and then suddenly darker—pitch. They had shut off the lights at the sides of the stage. Little pinpricks appeared, moving along the aisles. We used to do candles like this at church, when I was a kid, on Christmas Eve. You light the edges, and the edges spread inward. The rate of the spread increases exponentially, and the effect is so unexpected, when, at the end, you have half the group lighting the other half’s candles, it always seems like somebody flipped a switch. That’s how it seemed now.

The clouds had moved off—the bright stars were out again. There were fireflies in the trees all over, and spread before me, far below, was a carpet of burning candles, tiny flames, many ten thousands. I was suspended in a black sphere full of flickering light.

And sure, I thought about Nuremberg. But mostly I thought of Darius, Jake, Josh, Bub, Ritter, and Pee Wee, whom I doubted I’d ever see again, whom I’d come to love, and who loved God—for it’s true, I would have said it even if Darius hadn’t asked me to, it may be the truest thing I will have written here They were crazy, and they loved God—and I thought about the unimpeachable dignity of that love, which I never was capable of. Because knowing it isn’t true doesn’t mean you would be strong enough to believe if it were. Six of those glowing specks in the valley were theirs.

I was shown, in a moment of time, the ring of their faces around the fire, each one separate, each one radiant with what Paul called, strangely, “assurance of hope.” It seemed wrong of reality not to reward such souls.

These are lines from a Czeslaw Milosz poem

And if they all, kneeling with poised palms,

millions, billions of them, ended together with their illusion

I shall never agree. I will give them the crown.

The human mind is splendid; lips powerful, and the summons so great it must open Paradise.

That’s so exquisite. If you could just mean it. If one could only say it and mean it.

They all blew out their candles at the same instant, and the valley—the actual geographical feature—filled with smoke, there were so many.

I left at dawn, while creation slept.